Engaging Students: Essays in Music Pedagogy, vol. 4, Engaging Students Through Jazz

Bringing Jazz Repertoire, Improvisation, and Active Thinking into the Study of Motives

Timothy Chenette, Utah State University

Motives in music are a standard topic for music theory texts. These building blocks of melody are often described as important because “composers must maintain the delicate balance between repetition and its many degrees of variation, on the one hand, and the introduction of new material on the other” (Laitz, 364). Most books do not make explicit why students who do not think of themselves as composers must understand motives, but several ideas come to mind:

- Motivic analysis helps us understand the way a piece is put together—its “narrative”—which can have implications for performance.

- Cataloging motivic transformations gives us a window into how composers think and work.

- Motivic awareness might help our students in their own improvisations and compositions—activities explicitly advocated in at least one recent call for curriculum reform.

The first two goals are well-served by observation and analysis, and textbooks do a good job of these—presenting motives as something useful to expert composers, giving examples from canonic literature for contemplation, and (often) giving extensive catalogues of ways motives have been transformed by notable composers. The third goal, however, requires active thinking by students: going beyond identification of what others have done, and actually using motives in improvisation or composition themselves. These active tasks are important in and of themselves, and they are also important tools that improve students’ skills of observation and analysis. Fortunately, training in jazz improvisation provides a model for active understanding of motives. Improvising musicians face the same tasks described above, balancing repetition and the generation of new material: as David Baker says, introducing a catalog of motivic transformations on p. 95 of Jazz Improvisation, “The task of the player is to use repetition skillfully and subtly. Exact repetition of an idea more than two times, except for special purposes, is rarely effective.” Yet a review of eight standard music theory textbooks found not a single jazz excerpt or improvisation in discussions of motives. Inviting improvisation and other practices derived from the study of jazz into our study of motives, whatever the repertoire, encourages more active understanding. In addition, bringing jazz repertoire into the classroom can demonstrate to a wider variety of students that their preferred repertoire is relevant to the music theory classroom, and gives all students some idea of the importance of motivic thinking outside the classical canon.

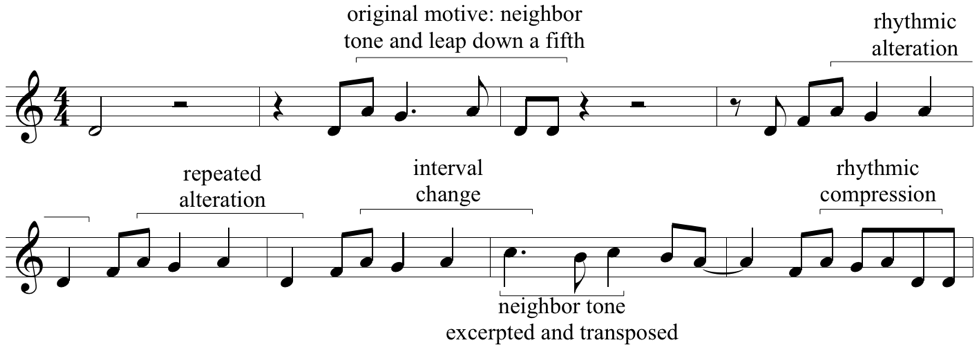

An initial step in this direction is the incorporation of transcriptions of famous jazz solos into our analytical corpus. This is an opportunity to expand the canon of music taught in theory classes to overlap with the canon absorbed by students in jazz programs who often inhabit the same schools. It also makes productive use of a common practice among our jazz majors, that is, transcribing and emulating the music of the “greats” in order to incorporate their techniques into one’s own skill set. Jerry Coker’s Improvising Jazz states on p. 14, “Just as the young composer learns much about his [sic] craft by listening to music while following the score, the beginning improviser can progress more rapidly by reading a transcription of an improvised solo while listening to the recording.” The annotated example below from Miles Davis’s famous solo in “So What” (transcriptions can be found on the internet) demonstrates a tight web of motivic transformations, and could lead to a discussion of how such transformations might arise spontaneously (or, perhaps, over multiple performances) in improvisation, in comparison to the sometimes more contemplative activity of composition. The solo could also foster discussion of:

- How motives are used to articulate form: the original motive in the transcription below usually, but not always, returns in some form when the solo returns to the opening Dm/D Dorian chordal/modal context.

- How some motives in the piece are used more fleetingly, perhaps characteristic of improvisation, which necessarily draws on stream-of-consciousness thinking at times.

- The ways the motives interact with the modal context: for example, the way prominent pitches in motives emphasize structural pitches of the mode, the fact that the transposed neighbor tone in the second line emphasizes the unique part of the Dorian scale (scale degrees 6 to 7), and (not included in the example) the use of different motives when the chord and mode change.

- How motives relate to, or grow out of, each other, as the repeated note in the third transcribed measure becomes prominent on its own through the course of a solo as a signal of phrase endings.

Figure 1. Transcription of the opening of Miles Davis’s solo in “So What.”

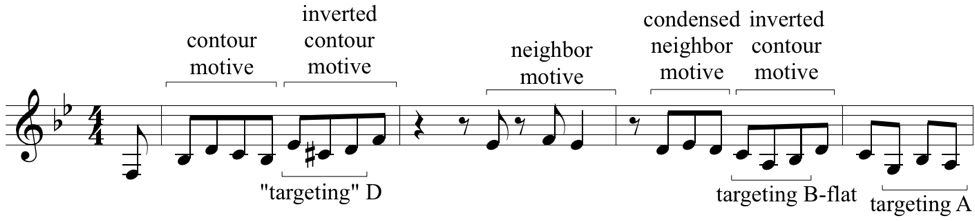

The excerpt from Parker and Gillespie’s “Anthropology” below (a transcription can be found in the Norton Anthology of Western Music, vol. 3) demonstrates a complex of three motives, and adds further complications:

- This is the tune’s “head,” which is not improvised, but these motives can often be found in Gillespie’s improvised solo. They are also, however, often absent.

- The piece is fast and chromatic, making it difficult to pick out the motives aurally. Do they still help the piece cohere in some way?

- Some of these motives are common idioms in bebop, particularly the “targeting” motive. This could lead to a discussion of the relationship between style and personal expression, and even a debate over whether to call such common devices motives at all.

Figure 2. Opening of Parker and Gillespie, “Anthropology.”

Yet if we want to foster truly active motivic thinking in our students, we should move past analysis to incorporate composition and, especially, improvisation. Here are a few ideas derived from common jazz studies activities, focused on active thinking about motives. These suggestions address, respectively: 1) in-class individual improvisation with some contemplation beforehand, 2) out-of-class individual improvisation with contemplation interspersed, and 3) in-class, on-the-spot improvisation that relies on listening to others. There are of course many more possibilities for activities, but these give some idea of the range. (Further suggestions can be found in texts such as Ed Sarath’s Music Theory Through Improvisation, which begins addressing motives on p. 8; there are also productive comparisons to be made with Peter Schubert’s articles on improvising canons and improvising Classical motivic structures in earlier volumes of Engaging Students.)

1) Have students select one motive from a transcription of a composition and create a melody with it in class. The melody should likely be 2 or 4 bars long, and could have a specified set of chords, which could be played by the instructor at the piano or guitar, or from an Aebersold recording or an iReal Pro playalong. The melody need not be in jazz style, and in fact taking ideas from one style into another may be especially interesting. The example melody below is based exclusively on the contour motive labeled in “Anthropology” above. At first, allow students time to experiment with the motive and work out something they would like to play before they are put on the spot. This can be especially effective and interesting if multiple students do the activity using the same motive and either compare their uses afterwards or build on each others’ ideas as each successive student plays (perhaps in immediate succession). For example, after a performance of the melody below, class discussion might note the use of inversion in the third measure, while perhaps criticizing the constant eighth notes and the uniform rhythm and metric placement of the motive. This would suggest ways for the next student to think about making their melody more rhythmically varied.

Figure 3. Hypothetical student improvisation using a motive from “Anthropology.”

2) Give students the opportunity to develop a motive across multiple performances. Make a recording of a backing track articulating chords available to students, then ask them as an assignment to improvise over it a certain number of times while recording themselves. After each time through, the student should listen through their improvisation and select their favorite parts to use as motives and develop further in their next attempt. (Asking students to notate their improvisation after each repetition might better facilitate reflection on their thought process, simultaneously incorporating aural skills.) This assignment allows students to progress at their own pace and develop motives with practice. Students should be encouraged to repeat motives to make a coherent solo. Ways to submit the assignment could include turning in electronic audio files of each iteration along with a journal of how they changed things each time and how they felt about the changes, or simply a recording of the final product with a brief analysis of their use of motives.

3) Give students the opportunity to interact aurally with each other through motives. This activity can be done either with the melody alone, or with the melody sounding over a repeating or predictable chord accompaniment. Ask students to improvise for as long as they like (possibly with some time limit) while focusing on a chosen motive, but then make eye contact with another student. This student should take over the improvised melody, changing the motive in some way. By the end of the activity, the motive should be completely transformed.

Integrating jazz practices and repertoires into our teaching of motives, then, is an opportunity to diversify the corpus we teach and to foster active thinking in our students. Jazz musicians regularly look at and analyze the works of the masters, but usually with the goal of incorporating what they learn into their own work. To the extent that music teachers incorporate jazz repertoire and adopt some of these methods of improvisation, we will foster this active understanding of motives in the rest of our students as well.

This work is copyright ⓒ2016 Timothy Chenette and licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution–ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.