Engaging Students: Essays in Music Pedagogy

My Undergraduate Skills-Intensive Counterpoint Learning Environment (MUSICLE)

Peter Schubert, Schulich School of Music, McGill University

For years I read to my students out of the textbook—that was my classroom lecture. When I taught harmony out of Aldwell and Schachter, I’d tell them which pages to skip, and when to substitute “never” for “occasionally.” I’d play the musical examples and tell the class what to look for in each one. In my own counterpoint texts one finds coy hints about things to discover in the musical examples (e.g., “The second counterpoint . . . may in some way illustrate the obsessive quality of jealousy”), but I couldn’t wait for the class to find the cool feature in Willaert’s duo—I blurted it out right away: “There’s a pattern seven quarters long that repeats three times!” (See my Modal Counterpoint, Renaissance Style, p. 170.)

It was pretty boring for all concerned, although it did ensure that the homework tasks were clearly defined. I read to them because, beginning in the eighties, my colleagues and I ruefully acknowledged that “students simply don’t read any more.” Saddest of all, not only did they not read the text, they didn’t read the musical examples.

But those days are over! A few years ago I concluded that the best use of classroom time is students performing music on the spot (whether improvised or prepared), for their colleagues, with a good dose of personal engagement on the part of the teacher. (I described the origins of this principle in “Global Perspective on Music Theory Pedagogy: Thinking in Music,” Journal of Music Theory Pedagogy 25 [2011]: 217-233. ) These activities permit a closer monitoring of each student’s strengths, weaknesses, and progress; they encourage students to develop musicality as well as musicianship; and they allow students to learn from each other as well as from the textbook and the teacher. Above all, they motivate the student by relating music theory to music making. In the following paragraphs, I will comment briefly on contrapuntal classroom activities and the roles of the textbook and homework.

The Classroom

The interaction between students and teacher could, as in other humanities courses, take the form of discussion and questions. But in music theory I believe it must more frequently take the form of “speaking” the foreign language, in this case, music. The music that is “spoken” elicits responses just as speech does: students can “speak” it to each other in the presence of the class and the teacher (e.g., one student improvising something or playing one line of a homework assignment and singing the other); then the rest of the class can sing it back, write it down, and comment, applaud, or gently criticize. In my counterpoint class we do a lot of improvising, and I have made four YouTube videos that demonstrate improvising canons: “Improvising a canon at the 5th above”, “Improvising a canon at the 5th below”, “Improvising a three-part canon part 1”, and “Improvising a three-part canon part 2”.

I encourage my students to improvise their homework, and to practice at home for their classroom performance, which eases the anxiety. Even if public classroom improvisation means at first riding roughshod over the rules for a time and producing hideous monstrosities, eventually the students’ comfort level with the material will increase, and each student will be motivated by having something personal at stake: “speaking” his or her original musical statement.

I tell the students it’s like when they start to take French in high school, and after the first day their grandmother asks them to “say something in French.” Now if she asks, “say something in music,” they’ll have something to say (and it won’t be a rote formula like the stale copybook phrase la plume de ma tante est sur le bureau de mon oncle).

Student comments on their musical experiences can be helpful to other students and the teacher. I have learned a lot from students in sessions of this type. A couple of examples occurred recently when I was teaching stretto fuga, a technique for improvising a note-against-note canon after one note (this technique, practiced in the Renaissance by boys improvising in church, is the one demonstrated in the videos linked above). In my textbook, the melodic motions allowed for making stretto fuga are printed in a line of text, like this:

imitation at the fifth above: sing or write 1 3↑ 5↑ 4↓ 2↓

(This means the leading voice may stay on the same note move up a third or a fifth, or down a fourth or a second.)

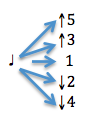

But in one class I wrote them vertically (on a staff), like this:

and a clever student observed that the vertical layout made it easier to spot the correct melodic motion (especially under the pressure of being the leader).

In another class on stretto fuga improvisation, one student was having difficulty following the leader. A classmate chimed in, saying that he had found that once you have started singing your note, you have to immediately ignore the note you are singing yourself, and shift your attention to the other person’s line. This is an essential tactic for succeeding at stretto fuga, and could lead to a richer musical behavior under performance circumstances. Nadia Boulanger used to suggest that a violinist playing a sonata should be able to sing the bass line of the accompaniment while playing the solo line. If a good performance entails attending to other parts, then stretto fuga will be a useful step towards developing that skill.

These observations (lining up the intervals and attending to the other part) are personal, based on discoveries by individuals; I want my classroom to be a place where such exploration can take place. In the old days, most of the personal contact I had with my students’ musicality was in the comments I wrote on their homework assignments, or made in my office hours.

Another good use of classroom time is to acquaint students with unfamiliar repertoire. We bemoan the fact that they don’t seem to know any Bach, much less any Palestrina. Classroom time is well spent if the teacher can convey not only general enthusiasm for a composer, but features or specific moments in a piece that are particularly lovable—and some students will immediately “get it.” Getting to know whole pieces from the inside is essential to putting the short homework exercise in its place: it is a fragment that will be useful in making something like the lovable piece.

The Textbook and Homework

If classroom time is to be spent with one student haltingly playing and singing her homework or improvising, the class haltingly singing back and commenting, and the teacher enthusiastically raving about the merits of Willaert, then how and when does the written work get done? MUSICLE focuses on skills, develops confidence, and gives the student a personal stake in the process, but there is more to counterpoint than what can be performed in the classroom. Music in many parts, mode, sophisticated techniques and architectural challenges, these require more deliberation and instruction. To cover these matters we need a textbook, which the students read on their own, and homework, which they likewise do on their own.

The textbook has to speak directly to the student, and the instructions for the exercises have to be crystal clear. I think there are very few textbooks that you can turn your students loose with, unsupervised. Many are too long-winded, too complicated, and pitched too high. These are manifestos secretly aimed at the teachers who will teach from them. I suppose we textbook writers secretly want to brainwash the teachers first, and only afterwards the students.

Conclusion

If the most important thing to me is that my students be musically active in front of each other, I have to do it in the only place where I’m legitimately in charge: the classroom. Under these circumstances I am both a drill sergeant (“next person to the piano”) and a facilitator (“what do you like about that solution?”), and I need a textbook that is a true DIY manual. It’s probably not possible for MUSICLE to be wholly like Sugata Mitra’s “Self-organized Learning Environment” (you may also find the SOLE support pack and the SOLE toolkit to be useful), which is “curious, engaged, social, collaborative, motivated by peer-interest, and fueled by adult encouragement and admiration,” but there are definite advantages to moving in that direction. The two requirements for such a shift in music-educational methods are: teachers willing to ask students to sing, play, and make mistakes, and simple textbooks that invite discovery and promote activity.

This work is copyright 2013 Peter Schubert and licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.