Engaging Students: Essays in Music Pedagogy

Creating Illusions: Practical Approaches to Teaching “Added Value” in Audiovisual Artworks

Colin Roust, Roosevelt University

Take a moment to study this image. What do you notice and how would you describe what is happening here?

“Brazilian flotilla 5,” uploaded by Vinicius1 to stock.XCHNG.

“Brazilian flotilla 5,” uploaded by Vinicius1 to stock.XCHNG.

Without any context, of course, there are any number of things that could be happening. If we imagine a story for the image, we might say:

“The first two planes are breaking away from the other two.”

“The last plane has almost caught up to the rest of the group.”

“Something is wrong with the last plane! It’s falling behind!”

“What happened to the fifth plane?”

In each case, the addition of language brings new, richer meaning to the static image of four planes. It enhances, shapes, perhaps even distorts what we see in the image. That these sentences create meaning is a result of what film sound theorist Michel Chion (1994, 5) calls “audiovisual illusion, an illusion located first and foremost in the heart of the most important of relations between sound and image…what we shall call added value.”

I have taught film music courses as both semester-long offerings at Oberlin College and as 6-week summer courses at Roosevelt University. At Oberlin, the classes generally consisted of a balanced mix of music majors and non-music majors, with only the occasional film major. At Roosevelt, all of the students (so far) have majored in subjects other than music and film studies. Regardless of the institution or the students’ majors, however, I find that most of them come into the course believing that certain music is “right” for a given film scene. What they are initially reluctant to accept is that there is always more than one “right” music for that scene. Indeed, the perception of music and images together shapes the meaning of the audiovisual scene, so that the whole is greater than the sum of its parts.

To demonstrate this point, I begin the course by playing a 25-second, stock-footage video of military jets:

Added Value Clip (Colin Roust) from FlipCamp on Vimeo.

Without sound, the clip could be anything, much like the photo at the beginning of this essay. But once music is added, the students quickly put the clip into a larger (imagined) narrative. For example, when they see the planes and hear Kenny Loggins’s “Danger Zone,” the students describe the pilots as hot shots or “bad boy” heroes, much like Tom Cruise’s Maverick or Val Kilmer’s Ice Man in Top Gun. With Dmitri Tiomkin’s song “Mission Accomplished,” from The Guns of Navarone, the students describe the jets as having just won a battle. Philip Glass’s “Pruitt Igoe,” a cue from Koyaanisqatsi, generates tension for most students; the pilots are waiting, anticipating something. “Running One,” from Tom Tykwer’s score for Run, Lola, Run generates a different kind of tension. Some of the fighter pilots are now perceived as menacing, threatening villains.

This exercise encourages students to experience the significance of added value. No musical cue is inherently, essentially “right” for a given image. Rather, somebody chose to combine this music with that image. The apparent “rightness” or “naturalness” of that artistic choice shapes our perception and, ultimately, guides our interpretation and understanding of what is happening.

To reinforce this exercise, I have the students face this kind of artistic choice from a creative perspective by completing a Silent Film Scoring Project. The project is introduced as early as possible in the semester, during the second class meeting or the second week, so that students can apply their new “insider” experience of film and their awareness of the audiovisual illusion to analyses and discussions throughout the remainder of the course. In smaller-sized classes, students work alone; in larger classes, students work in three-person production teams, with one student as the director (responsible for the artistic vision of the project), one as music supervisor (responsible for selecting appropriate music to realize the director’s vision), and one as editor (responsible for creating the final cut of the film). Depending on the length of the term students have either one or two weeks to complete the project.

Learning objectives:

- Gain familiarity with basic video editing software.

- Gain familiarity with basic principles of video and audio editing.

- Explain three strategies for scoring films: composition, improvisation, and compilation.

- Recognize and evaluate the variety of solutions possible when scoring a film.

- Apply basic concepts of audiovisual analysis in discussion and a short comparative analysis paper.

Materials needed

I provide each student/team with one blank DVD and with a copy of a film that is in the public domain. One-reel films from the nickelodeon era work especially well, since they tend to be between 5 and 10 minutes long. To facilitate comparative analysis, multiple students/production teams are assigned the same film. Finally, because my students have had little to no experience with music and video editing, I also lead a one-hour workshop on basic video editing software (Windows Movie Maker or iMovie).

Method

The project is introduced with a discussion of scoring strategies based on Fred Karlin’s Listening to Movies (1994, 78–84): playing the drama, hitting the action, playing through the action, phrasing the drama, and playing the psychological subtext. In addition to discussing concepts such as spotting and sync points, we focus on the three strategies used to create scores during the silent era: composing an original score, improvising an accompaniment, and compiling a score from any pre-existing music of their choice. Students are free to select any of these strategies, though any improvised scores must be recorded and synchronized on the finished DVD, rather than performed live in class. The prompt for the project follows the standard procedure for producing commercial films:

Production phase

Already completed when the students are handed the fine cut of the film (edited images without any sound).

Spotting session

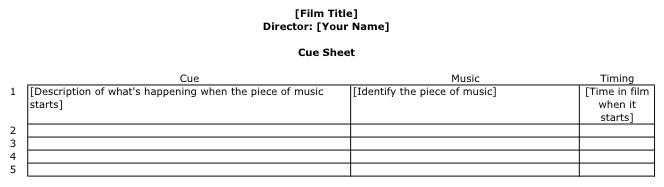

While watching the film, each student/team decides what kind of music to use for each cue, when each cue should begin and end, what sync points they want to emphasize, and whether or not to include any sound effects or dialogue. (The sound effects and dialogue are not explicitly encouraged, but are not prohibited.) At this point, the student/team creates the cue sheet to use as an editing script.

Cue Sheet Template distributed as a Microsoft Excel file.

Cue Sheet Template distributed as a Microsoft Excel file.

Post-production

Using basic video editing software, the student/team creates and adds a soundtrack to their film. If any changes to the plan are made, the cue sheet must be revised to reflect the final cut of the film.

Distribution

Using DVD authoring software (such as iMovie or Windows DVD Maker), the student/team creates a finished DVD of their film.

Exhibition

Each film is screened in-class. The student/team gives a short presentation—no longer than five minutes—about the creative decisions made in creating their score. Discussion after each screening is focused on the clarity and execution of the artistic vision, and on a comparison with the other scores created for the same film.

Final Product

Each student/team submits a finished DVD of their now-synchronized-sound film and a simple cue sheet for their score. When students work in a production team, I also have them write a short, three-to-five-page analysis paper comparing their score to their colleagues’ scores for the same film. As an example, a business major with no background in film studies or music courses chose to create a compiled score using various pieces of classical music:

Student Project #1 from FlipCamp on Vimeo.

With the length and slower pacing of the cues, the student sought to balance the faster activity of the images, giving a greater sense of continuity to each stage in the plot’s development. In contrast, a psychology major in the class aimed for an “authentic” nickelodeon feel by using “old timey” piano music:

Student Project #2 from FlipCamp on Vimeo.

The editing of this student’s score had faster pacing and more sync points, responding to key moments in each scene. This student also relied on a contrast of major and minor modes to suggest the inherent innocence of the beggar and the evilness of the hand.

Every time that I assign this project, I am consistently pleased and excited by the creativity and critical thought demonstrated by my students. In one particularly memorable case, four production teams had been given the same scene from White Shadows in the South Seas, at the arrival of Sebastian’s ship arrives on an island in the South Pacific. The scene begins with the islanders gathering on the beach as Sebastian is rowed ashore by his men. Dr. Lloyd sits on the beach, clearly unhappy. The two angrily confront each other and eventually come to blows. When one of Sebastian’s sailors shoots Lloyd, the islanders run in panic. In the chaos, Lloyd finds the chief’s daughter and dies in her arms. One of the student scores used cliché melancholy and love cues to focus our attention on Dr. Lloyd, the marooned, alcoholic doctor who had fallen in love with an indigenous girl and who feared that the arrival of whites would ruin the island paradise. Another score contrasted romantic-era orchestral music with percussion-dominated pieces to emphasize the indigenes as primitive and savage. Yet another used cues from a variety of action and war films to emphasize Sebastian’s crew as ruthless invaders and the indigenes as sympathetic victims. Due to an overabundance of sync points, this score made the scene feel like a Keystone Kops-style comedy. The final score consisted entirely of popular songs that had been selected based on a perceived link between the action on screen and the song’s title or lyrics. Taken as a whole, these scores became a vehicle for introducing students to the concept of style topics, or topoi, an essential feature of most mainstream film music.

Throughout both of these exercises, students learn fundamental concepts of film music by disrupting the traditional audiovisual experience. By exposing the artificialness of film music, the added value exercise helps students evaluate a given film’s score in the context of what choices the filmmakers did and did not make. This makes the students more keenly and critically aware of what effects the filmmakers sought to create and how effective those creative decisions are. The Silent Film Scoring Project reinforces this by giving the students practical, hands-on experience with these types of creative decisions. In their projects, the students synthesize course concepts and defend their creative decisions. By beginning the semester with these two experiences, the students encounter all of the films in the remainder of the course through the lens of these fundamental questions: What is happening in this scene? How does the sound enhance, shape, or distort what is happening? In other words, what audiovisual illusion is being created by sound and images, and what added value is created by that illusion?

This work is copyright 2013 Colin Roust and licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.