Engaging Students: Essays in Music Pedagogy, vol. 6

Part Writing Can Be Student Centered

Timothy Chenette, Utah State University

In recent discussions of student-centered music theory pedagogy, part writing is often treated as an albatross. In this journal, Richards (2015) decries a focus on part writing as one source of music theory’s “anachronistic priorities” that preclude more “pluralistic encounters” with music, while Kulma and Naxer (2014) argue that part writing “limits the engagement and agency of our students” and that de-emphasizing part writing will “create a better learning environment.” Elsewhere, Schankler (2013) points out that “the limitations of chorale writing can make it very, very dry stuff, especially compared to the vividness and expanse of what’s possible in music.”

Nevertheless, part writing clearly has benefits. Schankler admits, in the same post, that it has “immense utility as a teaching tool.” And both Follet (2013) and Snodgrass (2016) celebrate the ability of part writing to engage students in what Snodgrass calls a “musical experience,” to help them learn to balance vertical and horizontal aspects of music, and to teach problem-solving skills that generalize to other disciplines.

I agree with Schankler, Follet, Snodgrass and others that part writing is useful and can be empowering to students, and I agree with Richards, Naxer, Kulma, Schankler and others that spending huge amounts of time on “very, very dry stuff” can be detrimental to our students’ experience of music theory as a pluralistic discipline, and as a result this article will present some ideas on how to maximize the positive pedagogical value of part writing. In particular, we should:

- rethink what part writing is;

- help students build productive mental models; and

- teach part-writing not as an end in itself but as a key that unlocks exciting abilities.

1. What is Part Writing?

Kulma and Naxer (2014) define part writing as “the specific combination of voice leading and harmonic syntax in the eighteenth- and nineteenth-century styles that has appeared in textbooks since Walter Piston’s (1941) Harmony,” a tradition strongly associated with the chorales of Johann Sebastian Bach. This historical/stylistic specificity is a major factor in many negative views on part writing. Many music theorists know that part writing’s relevance actually extends to a huge repertoire of music ancient and modern, but if students aren’t making these connections themselves, we need to do so as an integral part of our teaching.

Jazz in particular has an important presence in many music departments, and “voice leading” is a standard topic of discussion and training for jazz musicians. It may be astounding to many music theorists, but there is sufficient demand from the music-making public for information on voice leading in a jazz (particularly jazz guitar) context that there are numerous commercial websites on the subject. Typical examples like this one (N.D. 2018) usually describe parsimonious voice leading and outer-voice contrary motion as the most important principles, but a quick investigation of “guide tones” (Boornazian 2018) and “7-3 resolutions” (Devine 2011) will demonstrate many more points of contact with “classical” voice leading. In my Theory 1 classes, I include a vocal jazz arrangement, based in part on this short reading (fleshed out in class activities and short assignments).

Part-writing principles extend into other genres as well. Deke Sharon, the guru of collegiate pop a cappella, includes principles of part writing as the first three items in his “Universal Arrangement Critique” (Sharon 2013) (while taking an obligatory swipe at the “‘rules’ you learned in theory class”). Barbershop arranging guidelines include part-writing principles such as appropriate voice ranges, parsimonious voice leading, and rules of good doubling, and I have had success asking students to write barbershop arrangements of Civil-War-era tunes as a way to apply their skills and knowledge to new repertoires. There are plenty of pop and rock songs that do not show close attention to part writing, but there are also plenty of chordal sevenths and leading tones that resolve “correctly,” while vocal doo-wop and keyboard-based songs often use classic “3+1” keyboard spacing and doubling with mostly parsimonious voice leading. We may know this—but it is important to bring these repertoires into our classes, and talk about important part-writing differences among genres, if we want our students to see the connections.

We also need to make sure students understand what part writing is for. In particular, most of us have probably encountered the misconception that music theorists think part writing represents “rules for writing good music.” Demonstrating connections to diverse genres, as above, is important, particularly since certain rules are not applicable in certain genres. So is pointing to the cognitive basis (Huron 2016) of some of the principles of part writing, though of course culture shapes how part writing and cognition interact.

Even when teaching part writing as a historical method of composition, we should help students understand the roles of the “rules” we teach. When introducing part writing, I wear sandals with white socks, black pants and a brown belt and tie my tie too short. (Planning this outfit is pretty fun--the possibilities are endless.) Despite my students’ revulsion, there is nothing innately wrong about wearing sandals with socks: one could imagine a culture where this is totally normal. Other choices, like wearing black pants with a brown belt, might be justified by cognition (“our brain prefers colors that are easier to distinguish”) but are also subtle: many people might not even notice the faux pas even though they wear clothes every day, but it would be a bad idea if you wore these to a job interview at a fashion store. Similarly, the amateur music-lovers who heard J.S. Bach’s church cantatas might not have noticed if he’d slipped in some parallel fifths, but he probably wouldn’t have gotten the job if his composition portfolio were full of them.

2. Building Better Mental Models

If students are to truly understand the integration of vertical and horizontal elements embodied in part-writing principles and develop their problem-solving skills, they need good mental models. This works well for some students without much intervention: the student who is able to hear chords and lines in their head may be able to quickly ascertain whether the vertical structures they are writing sound good and whether the horizontal lines are easy to sing, while the student who plays a polyphonic instrument such as the piano may have internalized appropriate physical gestures to represent verticalities and actions that connect these with good voice leading. Other students, however, lack these models.

I have had some success with such students with a model that combines visual, kinesthetic, and sonic elements. I set up circles of seven chairs each around the room, label each chair with a scale degree or solfège syllable, and assign students to these circles in groups of at least eight. Each group has roles assigned as follows:

- Three students (“movers”) sit on chairs and move around the circle to represent physically the motion of the upper three voices.

- One student (another “mover”) stands just outside of the circle and moves around it to represent physically the motion of the bass.

- Four students (“singers”) stand to the side and sing the parts indicated by the physical motion of the other four students. (Extra students can double singing parts.)

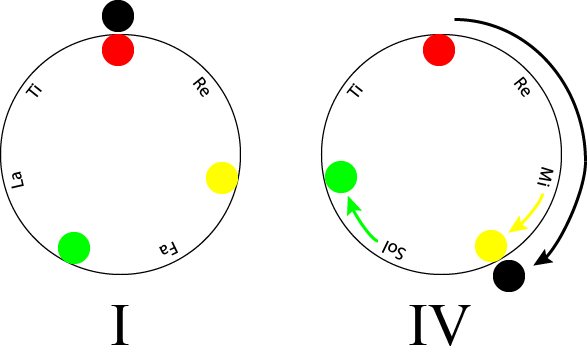

The four movers work together to identify the smoothest part writing of a given progression physically, then the four singers sing along as the movers repeat their physical motions. For example, I might ask students to start on the tonic chord, then move to the subdominant. The movers easily work out this voice leading, to which the singers have no trouble singing along:

Example 1: Tonic to Subdominant

Example 1: Tonic to Subdominant

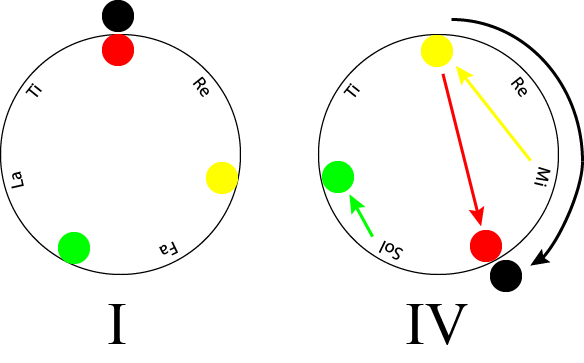

It’s fairly easy to demonstrate why the following voice leading is not preferred, as the frantic scrambling of the movers dramatizes the difficulty for the singers:

Example 2: Frantic Scrambling

Example 2: Frantic Scrambling

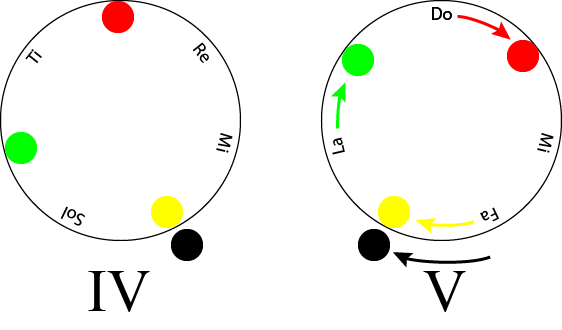

Parallel motion with the bass is visually obvious in progressions like the following:

Example 3: Parallel Motion

Example 3: Parallel Motion

Upper-voice doubling can present an awkward physical situation for the movers, but one student can simply stand in front of the other.

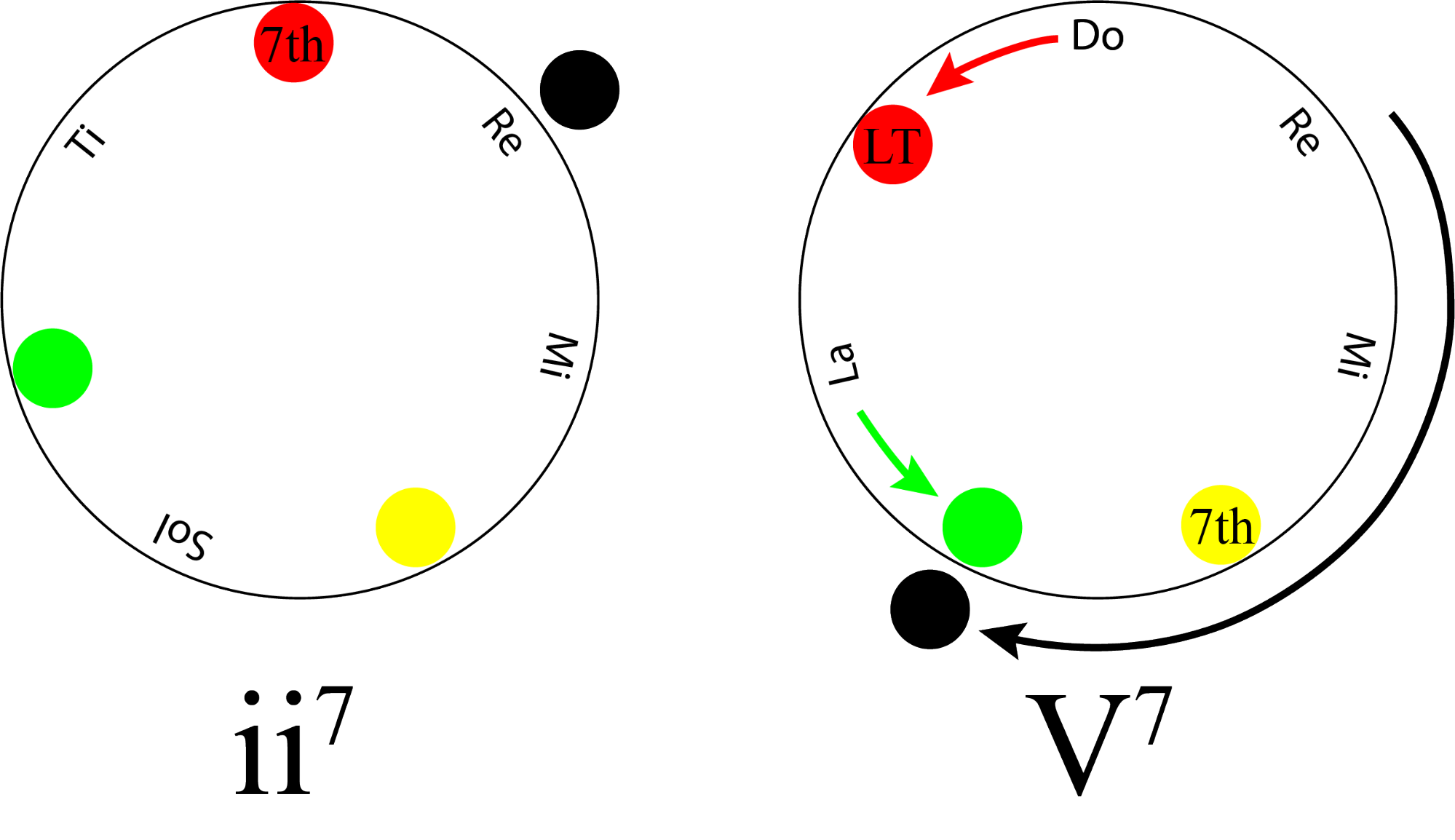

Understanding voice leading holistically and physically through this model also works well with seventh chords, making clear why the fifth of a chord must sometimes be left out. Awareness of chordal sevenths and leading tones can be enhanced through gestures (say, raising your hand when you’re the seventh) and/or drawing an arrow in the correct direction of resolution on the leading tone’s label.

Example 4: Seventh Chords

Example 4: Seventh Chords

While students must be reminded to continue to picture this model when putting pen to paper, they have mentioned in course evaluations that this kind of thinking helped them to keep track of the vertical and horizontal aspects of voice leading simultaneously.

3. Unlocking Awesome Powers with Part Writing

Both Snodgrass (2016) and Follet (2013) describe asking their students why they do part writing; in each case, the students immediately respond with what Amabile (1997) calls “extrinsic motivators”—those generated by an agent external to the student (i.e., the teacher). Unfortunately, the controlling extrinsic motivators mentioned by Snodgrass’s and Follet’s students are often antagonistic to intrinsic motivation: “as extrinsic motivation for an activity increases, intrinsic motivation must decrease” (Amabile 1997, 44–45.). While I recommend teachers investigate the types of extrinsic motivators Amabile describes as less harmful to creativity (pp. 45–46), student work and engagement will be even better if we can tap into intrinsic motivators. For some students, a window into Bach’s brilliance or an opportunity to solve puzzles is motivating enough. We will benefit other students, though, if we consistently position part writing not as an end in itself but rather as a key that unlocks abilities students value. Consider the following learning objectives:

- Students will be able to demonstrate their understanding of 18th-century diatonic part writing through four-part chorale harmonizations.

- Students will be able to compose a diatonic hymn setting and a vocal jazz arrangement in four parts using appropriate voice leading.

Objective 2 much more clearly emphasizes the abilities students will gain from this subject. (The exact abilities one wishes to emphasize may differ by institution and instructor: my institution has a high concentration of churchgoing students and a strong jazz program.)

Embracing such a perspective on part writing must also have an effect on a class’s approach to assessment to be effective. A teacher who lists learning objective #2 in the syllabus but assigns only chorale harmonizations will not effectively communicate these exciting possibilities to students. There is of course no single best way to align learning objectives and assessments, but for my most recent Music Theory 1 class, I had students take repeatable, computer-graded quizzes on “classical” part-writing principles and on jazz-specific principles; in class, we did both the physical exercises described above and more traditional pen-and-paper part-writing activities. As culminating projects, students created and recorded both a hymn arrangement and a vocal jazz arrangement, two practical and creative applications of voice-leading skills. With these projects as our goal all along, students never seemed to feel that part-writing was an abstract skill relevant only to a single kind of piece from the Baroque; rather, they were intrinsically motivated by the fact that part writing gives them abilities they can put to use right away in their church choirs, jazz ensembles, and beyond.

Conclusion

Must part writing remain an albatross, a curse on the student-centered learning environment? No. We should absolutely make sure we leave room in our curricula for the “pluralistic encounters” with music theory advocated by Richards (2015). But instead of doing so only by “greatly limiting” the amount of time we spend with part writing (Kulma and Naxer 2014), let’s invite part writing into at least some of these student-centered pluralistic encounters. Its value extends far beyond the style of Bach, so long as we help students see this; we can help students build better mental models to gain the insights we want them to gain; and we can empower students by being explicit about the awesome powers they can gain through an encounter with this exciting set of skills.

References

Amabile, Teresa M. 1997. “Motivating Creativity in Organizations: On Doing What You Love and Loving What You Do.” California Management Review 40, No. 1: 39–58.

Boornazian, Josiah. N.D. “How to Use Guide-Tones to Navigate Chord Changes.” Learn Jazz Standards (blog). Accessed July 8, 2018. https://www.learnjazzstandards.com/blog/learning-jazz/jazz-theory/use-guide-tones-navigate-chord-changes/

Devine, Scott. 2011. “II V I Jazz Lick #1 Bass Lesson with Scott Devine (L#24).” Youtube video, 8:36. Accessed July 8, 2018. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2BVs6b2F_aY

Follet, Diane. 2013. “Tales from the Classroom: Why Do We Part-Write?” Journal of Music Theory Pedagogy E-Journal 1.

Huron, David. 2016. Voice Leading: The Science Behind a Musical Art. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Kulma, David, and Meghan Naxer. 2014. "Beyond Part Writing: Modernizing the Curriculum." Engaging Students: Essays in Music Pedagogy 2. http://flipcamp.org/engagingstudents2/essays/kulmaNaxer.html

Piston, Walter. 1941. Harmony. First edition. New York: W. W. Norton.

Richards, Sam L. 2015. “Rethinking the Theory Classroom: Towards a New Model for Undergraduate Instruction.” Engaging Students: Essays in Music Pedagogy 3. http://flipcamp.org/engagingstudents3/essays/richards.html

Schankler, Isaac. 2013. “On Lying To My Students.” New Music Box (blog). New Music USA, September 26, 2013. Accessed May 29, 2018. https://nmbx.newmusicusa.org/on-lying-to-my-students/

Sharon, Deke. 2013. “Deke’s Universal Arrangement Critique.” Deke Sharon’s Aca-Blog (blog). The Contemporary A Capella Society, January 7, 2013. Accessed May 29, 2018. http://www.casa.org/content/dekes-universal-arrangement-critique

Snodgrass, Jennifer. 2016. “Why Do We Part Write?” Bridging the Music Theory Gap (blog), September 13, 2016. Accessed May 29, 2018. https://bridgingthemusictheorygap.wordpress.com/2016/09/13/why-do-we-part-write/

N.D. “Voice Leading.” The Jazz Piano Site. Accessed May 29, 2018. http://www.thejazzpianosite.com/jazz-piano-lessons/jazz-chord-progressions/voice-leading/

This work is copyright ⓒ2018 Timothy Chenette and licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.