Engaging Students: Essays in Music Pedagogy, vol. 6

A Student-Centered Approach to Composing Popular Music in the Theory Classroom

Bruno Alcalde

Teaching technical and theoretical aspects of popular music at the college level brings about some pedagogical challenges. While many institutions focus primarily on music of the so-called common practice, to simply transfer typical concepts and strategies from one repertory to another would be counterintuitive. Popular music, given its practices, is hardly amenable to a formalization of the learning experience in the way historical styles are. Nevertheless, some of the traditional theory classroom strategies can be fruitfully transferred if adapted to the distinct characteristics of the repertory. One such possibility is to use model or style composition—a strategy widely used in the study of historical styles—to engage with theoretical and analytical ideas through hands-on and creative activities, which favor an experiential approach also shared by popular musicians. How can an instructor rely on composition as a pedagogical tool and build a framework that still accounts for these more flexible modes of learning so relevant to popular music?

This spring, I developed a course called Analysis and Composition of Popular Music, which serves as a general course on the subject, attracting students who are interested in popular music and might be music majors, but also minors and non-majors. Students arrive with widely diverse backgrounds, interests, and levels of expertise, ranging from merely curious to semi-professional producers and musicians. Many of these students have a considerable baggage of informal learning—even if only through listening—sometimes mixed with some formalized training; others never composed or played an instrument. This situation also afforded the opportunity of teaching analytical and compositional concepts by fostering experiential modes of learning in the classroom (also explored by Green 2002, Feichas 2010, McPhail 2012, and Jemian 2017), emphasizing listening and model composition with a popular music repertory.

Composition is a fairly usual pedagogical tool in the common-practice theory classroom, especially within constraints of historical styles. Different uses of model composition are discussed, for instance, by Eckert (2005) in relation to writing minuets in the galant style, Parker (2006) on composition of sonata form movements, and Rabinovitch and Slominski (2015) on eighteenth-century style improvisation. Among the benefits of this kind of strategy, Cook (1996, viii) mentions its possibility to “inculcate and nurture basic analytical concepts in a practical context…keep[ing] the analysis linked as closely as possible to music.” Cook also indicates the integrationist stance in the use of composition as a pedagogical tool, which combines several subjects taught separately—harmony, counterpoint, composition, analysis, theory—in one practical activity. Byros (2015), engaging with composition of preludes in the style of J. S. Bach, addresses a related point when writing about the friction between “know-how” types of knowledge, common in eighteenth-century practice-oriented pedagogy, versus the “know-what” model emphasized by many modern music theory curricula.

Using model composition as a pedagogical tool in a popular music classroom, with a group comprising students of varied levels of expertise might seem pedagogically challenging; however, if modified, the strategy can align with the “know-how” types of knowledges of popular musicians, often comprising non-linear, group-oriented, and cooperative methods with a focus on sound (Green 2002). Thus, the class uses mostly non-score-based assignments, focusing on recorded tracks as the main objects of reflection and analysis, as well as the format of the student’s creative works. It is important to note that this reduced focus on notation aligns with the practices of popular music, demystifying the act of composing, and also fosters an inclusive profile, inviting a diverse group of students to contribute with the knowledge—formal or informal, musical or non-musical—they already have. Students, then, actualize a newly discovered concept into a creative and exploratory act which places students’ intrinsic goals at the forefront; each concept is promptly applied within a week’s time, and students write the music they can, depending on where they are in their personal and musical development. This class is organized by a weekly routine or cycle that starts with listening to a selected playlist based on a rotating topic, then discussion, and, finally, flexible application of the ideas through composition. In this essay, I describe this routine and showcase some of the results that were achieved during one of the weeks. This approach that culminates in a composition adds an intrinsic motivation to the learning process: that of creating something they are proud to share weekly in front of their peers, showing their personal discoveries and explorations. Furthermore, this process affords students ownership and autonomy of the explorations as well as tailoring the material to their diverse needs, interests, and backgrounds.

Routine

The routine suggested here involves weekly guided composition projects that explore rotating general popular music topics. In order for this to be feasible for a diverse group of students, it might not be ideal to use very local and overly technical aspects of music. Compositions have to either be performed in class or be presented as a recording. Even if they do not have experience in composition, this course has shown that students are quick to find ways to use software such as Garage Band, Ableton Live, or Logic Pro. In cases the software is not available to students, other freeware multitrack recording, such as Audacity, can be used. The following routine affords not only an exploration of creative concepts of popular music, but also a path for finding ways of expressing that creativity.

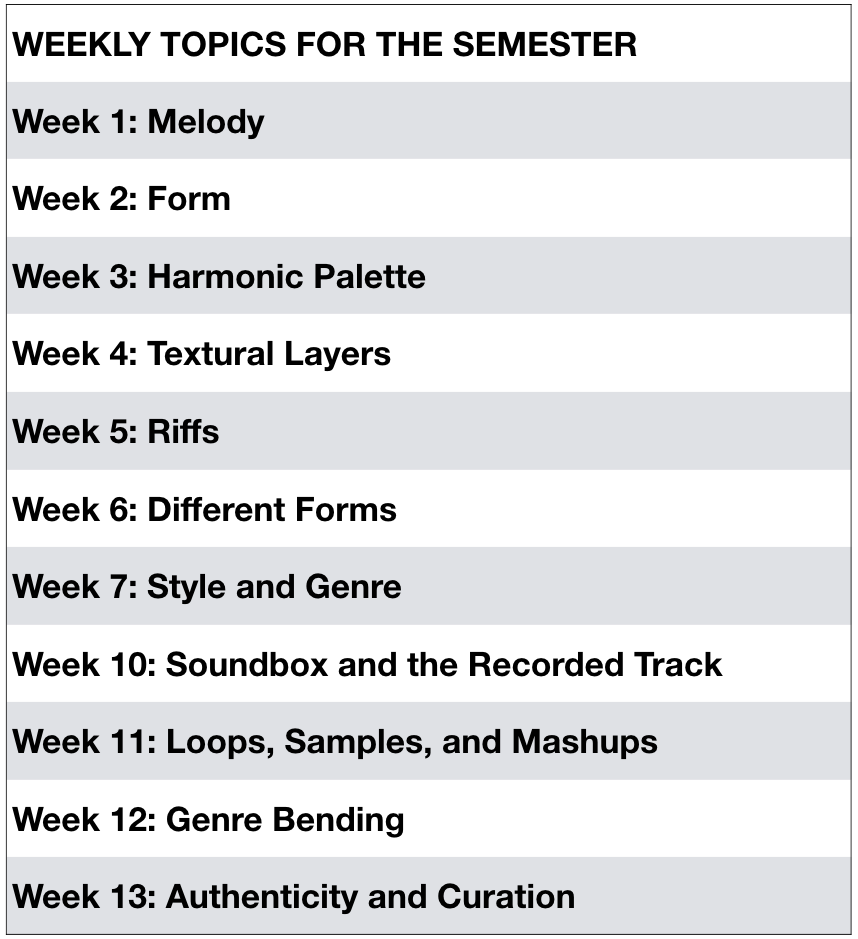

This specific course consists of two meetings per week, and each cycle starts with the meeting preceding the weekend (Thursday, in the case of a Tuesday/Thursday course) in order to allow for more time to work on the composition projects. The compositions are usually around one-minute long and rely on students’ choices of genres to explore the creative possibilities of the musical concepts, not restricting it to one type of music. I start with a list of pre-selected topics in the syllabus, but as the course develops, I take students interests into account and tweak the choice of subjects and repertory that work best for a specific group. Example 1 shows the topics chosen for this specific group during the spring of 2018. While most of the playlists were chosen by me, students were always encouraged to bring new examples from their preferred genres to the discussions in class. The specific topics I used aimed at being general enough to embrace a variety of genres and the different levels of expertise in class.

Example 1: List of topics throughout the semester

The handout that structures each week involves a playlist, a few theoretical/compositional concepts, guiding questions, and a composition project, which are provided in a handout before the first class of each cycle. As an example, I will use the handout from week 4, on textural layers. A brief 9-page reading from Moore (2012) introduces the concept and should guide the engagement with the playlist of 4 songs from different genres (the playlists usually range from 3 to 7 tracks). Students should also find a song from their repertory that uses textural layers in a way that interests them. Some open questions should also help the student’s focus while listening to the week 4 playlist, but there is plenty of space for them to engage however they would like. Finally, the handout also describes the composition project.

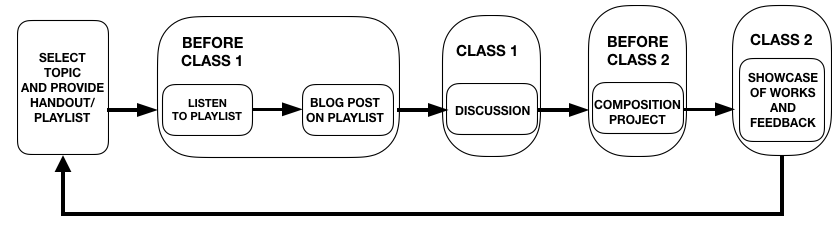

Example 2: Diagram of the routine

Example 2 shows a diagram of the routine/cycle for each week, which is related to Kolb’s experiential learning cycle (Kolb 2015, 66-68). The cycle begins with the distribution of the handout for the weekly topic. For the next class, students should have listened to the tracks critically, thinking about the concepts of the week, and write their ideas about the repertory on a class blog, which will inform the upcoming discussion. Class 1 (Thursday) consists of students sharing their perspectives about the music in relation to the primed concept. I facilitate the discussion by asking questions about their ideas (always reacting to the ideas they raise), while we listen to snippets of the music in the playlist to exemplify points. Several times, students suggest that we play a track that is not in the playlist, which they think serves as a good illustration of the concept, to contradict it, or to support a point they are making. As class 1 progresses, we end up with a few guidelines and perspectives on the repertory and the concepts, which are summarized on the board or verbally. After listening and discussing a group of pieces within the framework of a particular concept, students abstract these ideas as tools or strategies to be used in their composition project. Selected readings serve a supportive role in this routine in some weeks and are done as a way of reinforcing the concepts or facilitating their introduction, rather than being the main focus of the discussions. For week 4, their project is guided by a textural and formal graph, included in the handout, which should be explored in any genre they wish to compose.

Class 2, after the weekend, is a showcase and discussion of their work. Each student explains what they aimed to do within the constraints of the project, plays their music, and receives feedback from their peers and instructor. This creates a supportive environment formed by students focusing on different types of music but applying similar concepts. More experienced students help less experienced ones, by suggesting composition or production strategies. At the end of this class, the handout for the next cycle is distributed, and the routine repeats. As examples of the work done with the class, here are a few compositions for this week on textural layers, which the students consented with sharing publicly. Audio examples 3 to 7 were composed by students who are either minoring in music or non-majors, ranging in experience from never having studied theory or composed before this course, to more advanced formal training. (Example 3) (Example 4) (Example 5) (Example 6) (Example 7).

Final Thoughts

To learn by doing— experiential learning—puts a different weight on music theory and analysis, which are commonly thought of as hermetic and disconnected from the “real” musical experience. Model composition keeps these subjects “linked as closely as possible to music” (Cook 1996, viii) and emphasizes “know-how” types of knowledge (Byros 2015). As Eckert (2005), Parker (2006), and Rabinovich and Slominski (2015) show, this can be realized in diverse ways with eighteenth-century styles. In this essay, the same ideas hold true in modifying and further exploring the strategy with popular music repertories. By listening and analyzing in order to repeat the recognized strategies and tools in one’s own work, students discover, abstract, and apply the ideas themselves, with some guidance by the instructor. In the particular routine described here, the playlist listening is goal-directed, and that goal—a composition project—is intrinsic to each student. But it is also shared among peers. This fosters a cooperative and student-centered environment, in which the openness of having to show their compositions and getting feedback every other class creates a peculiarly supportive community, in my experience. Students witness the progress and explorations of their peers and help with criticism and suggestions—they are, at the same time, thinkers, makers, and listeners. As a means of evaluation of the composition projects, I used a grading rubric in which I would write my comments from a more formal perspective, which then integrates the informal learning activities with more theoretically organized ideas. This routine allows students and instructors, in cooperation, to create links between informal and formal knowledge, as Fleichas (2010) and McPhail (2012) suggest.

One of the main problems I envisioned with this course was that the different levels of expertise would create a chasm in class, leaving the less experienced group isolated and unmotivated. However, the classes lead to positive interactions, always with a genuine group effort to evolve. Whether the routine discussed here is used in selected weeks over the course of a semester, or serving to structure an entire course, it can afford this kind of creative environment because it is built around, and values, students’ contributions. These contributions happen in many ways, such as: (1) students’ personal perspectives on the weekly playlists, which help the group systematize the topics under study; (2) students’ compositions and discussion of the challenges of applying the concepts from the playlist in their own material; and (3) students’ feedback on the work by their peers. The repetition of the routine every week, instead of becoming redundant, allowed for building up on theoretical concepts, revisiting and refining them under different lights (for instance, how material from the week on form intertwines with the ideas on textural layers, used here as an example). Students blogs on the weekly playlist, as well as in-class discussions, showed that their engagement with the concepts facilitated increasingly detailed and structured descriptions and critiques.

There is certainly a lot of room for improvement and tweaking in this strategy, but the idea is not to make it rigid in any way. Rather, it can be changed to fit other repertories or goals, which can benefit from a student-centered and experiential approach. In my experience, students leave the class with a sense of achievement with their works, having explored many complex strategies and concepts of popular music from a personal and applicable perspective. In the end, this echoes Rogers (1951, 389) who proposed a humanist, student-centered approach to teaching some 70 years ago: one “learn[s] only those things which [they] perceive as being involved in maintenance or enhancement of [their] own self.”

References

Byros, Vasili. 2015. “Prelude on a Partimento: Invention in the Compositional Pedagogy of the German States in the Time of J. S. Bach.” Music Theory Online 21 (3). http://www.mtosmt.org/issues/mto.15.21.3/mto.15.21.3.byros.html.

Cook, Nicholas. 1996. Analysis through Composition: Principles of the Classical Style. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Eckert, Stefan. 2005. “‘So, You Want to Write a Minuet?’—Historical Perspectives in Teaching Theory.” Music Theory Online 11 (2). http://www.mtosmt.org/issues/mto.05.11.2/mto.05.11.2.eckert.html.

Feichas, Heloisa. 2010. “Bridging the Gap: Informal Learning Practices as a Pedagogy of Integration.” British Journal of Music Education 27 (1): 47-58.

Green, Lucy. 2002. How Popular Musicians Learn: A Way Ahead for Music Education. Burlington, VT: Ashgate.

Jemian, Rebecca. 2017. “Ho Hey, Having Some Say in Contextual Listening.” Engaging Sudents: Essays in Music Pedagogy 5.

Kolb, David A. 2015. Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development. 2nd ed. New Jersey: Pearson Education, Inc.

McPhail, Graham. 2013. “Informal and Formal Knowledge: The Curriculum Conception of Two Rock Graduates.” British Journal of Music Education 30 (1): 43–57.

Moore, Allan F. 2012. Song Means: Analysing and Interpreting Recorded Popular Song. Farnham, Surrey; Burlington, VT: Ashgate.

Parker, Sylvia. 2006. “Understanding Sonata Form through Model Composition.” Journal of Music Theory Pedagogy 20.

Rabinovitch, Gilad, and Johnandrew Slominski. 2015. “Towards a Galant Pedagogy: Partimenti and Schemata as Tools in the Pedagogy of Eighteenth-Century Style Improvisation.” Music Theory Online 21 (3). http://www.mtosmt.org/issues/mto.15.21.3/mto.15.21.3.rabinovitch.html.

Rogers, Carl R. 1951. Client-Centered Therapy: Its Current Practice, Implications, and Theory. London: Constable.

This work is copyright ⓒ2018 Bruno Alcalde and licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.