Engaging Students: Essays in Music Pedagogy, vol. 5

The Undergraduate Student-Faculty Colloquy: Cultivating Disciplinary Authenticity through Formative Oral Examination

Scott M. Strovas and Ann B. Stutes, Wayland Baptist University

The Colloquy: Introduction and Philosophy

It is perhaps a bit ironic that, in an e-journal dedicated to innovative teaching strategies, the authors of this essay promote a centuries-old form of assessment. While instructors are undoubtedly familiar with oral examination, or viva voce, their experience with it is likely limited to the qualifying and defense processes with which graduate studies culminate. Application of oral examination within undergraduate curricula is much less common (Symonds 2008; Huxham, Campbell, and Westwood 2012). Still, a number of recent pedagogy studies demonstrate the feasibility and educational benefits of oral examination in undergraduate programs (Asklund and Bendix 2003; Cantley-Smith 2006; Clouder and Toms 2008; Huxham, Campbell, and Westwood 2012; Iannone and Simpson 2012; Singh 2011; Thomas, Raynor, and McKinnon 2014).

In 2015, we implemented oral unit exams as part of a wholesale revision of our four-semester undergraduate music theory sequence intended to remove artificial impediments to the learning process. Chief among these, we believe, are textbooks, workbooks, and written exams. Today’s student learners hunger for experiential learning environments which offer real-life problem-solving scenarios through which to acquire, implement, and sharpen professional skills. Our students now engage scores—the primary materials of the discipline—from Day 1, as class time is dedicated to uncovering musical concepts directly from the repertoire and developing score-reading fluency. The oral assessment experience which we detail below reinforces the professional musician’s need to think and to communicate effectively in the language of the discipline: to engage a work of music efficiently, identify and articulate its salient features, perform it individually and collaboratively, and understand its place within the broader landscape of musical literature.

Put simply, the exams invite students to discuss scores with two experienced music professionals—their instructors. As mentors, we seek to alleviate the potential anxiety students might feel over reading “Oral Examination 1” in the syllabus and instead adopt the word colloquy, which Oxford English Dictionary describes modestly as “a talking together” or a “conversation.” Students must also sing, count, and conduct passages of the repertoire, thereby demonstrating the synthesis of concept and craft required of the professional to present an informed performance. We thus consider the colloquy, as a roundtable simulating professional discourse and activity, to be an apt replacement for written exams. As Singh comments, “in the real world, graduates are not just expected to write down all their responses or interactions” (248). Indeed, it is difficult to imagine a written exam which allows instructors both to assess and to hone the analytical tools and musicianship skills by which students engage musical literature, all the while equipping students with life-long communication skills.

Practically speaking, most colloquies take 10 to 20 minutes per student and occur during class time over several days. While this may present concerns of time management, we assign activities, such as visiting the ear-training/listening lab, completing analysis projects, and meeting with singing teams, to those students not directly involved in colloquies on a particular day. We also occasionally hold group colloquies, which both facilitate efficient assessment and foster collective understanding. Understandably, doubts about the feasibility of administering oral assessment will come from instructors at programs serving large student populations and involving full-time faculty, part-time faculty, and graduate assistants across several sections. Still, we believe oral assessment to be worth pursuing and direct these readers to models comprising 288 undergraduate environmental health students and 10 examiners, 108 first-year math students and 4 examiners including 2 graduate student tutors, 99 first-year biology students with an unspecified number of examiners, 75 undergraduate introductory psychology students and 2 examiners, and specific to music, 5-7 sections of first-semester music theory students instructed mostly by graduate teaching associates (see Anna Gawboy’s discussion in Section 6 of the linked paper, as well as her appendixed interview prompt).

Our colloquy is not designed to be a platform for on-the-spot comprehensive formal or harmonic analysis; rather, it is through the colloquy’s back-and-forth exchange that instructors measure how deeply each student applies the analytical tools presented in class to pre-assigned literature, repertoire from their applied studios and ensembles, or scores presented for discussion at sight during the colloquy. As Cantley-Smith notes, “oral examinations may enable an examiner to ascertain, in a comparatively short space of time, what a student knows as well as the depth of this understanding” (42). Since we are not confined to a preset list of questions, we are able to communicate uniquely with each student. The end result is an authentic direct assessment of what each student is able to identify, explain, and perform. Moreover, the colloquy has formative educational benefits, in that it “emphasizes process more than product” and “is used to provide feedback to pupils and teachers to promote further learning” (Atjonen 2014, 240). During the colloquy, instructors observe instantly whether a student engages the music using the processes modeled in class. For students performing poorly, the colloquy becomes a vivid learning moment during which we reiterate best practices. By and large, students we mentor within the colloquy respond positively with improvement from one colloquy to the next.

It is our experience that early and continued use of oral examination compels students to assume greater agency over their learning. Having just completed their second year, students of the revised curriculum’s initial class exhibit enthusiasm for the collegiate experience, resulting in demonstrably higher academic achievement and improved retention rates. One applied faculty colleague in our program confirms that “their talent level is very similar to past years, but I notice a significant improvement in the speed in which they understand concepts. They are much more able to ‘speak music’ and are actually excited about theory and music history.” A second colleague shares that she is “able to communicate with these students on an overall much higher level, much earlier. From even their first semester of study, they are now able to understand and participate in conversations about harmonic texture, form, and many other concepts that, in the past, came much later.” The colloquy thus provides an authentic and formative assessment environment which deepens student learning and accelerates the rate at which students progress through the curriculum.

These anecdotal assertions reflect benefits of oral assessment promoted in the secondary literature. Huxham, Campbell, and Westwood link oral examination quantifiably to improved academic performance, and qualitative studies involving student surveys repeatedly tie improved student engagement to the perception of validity and authenticity of oral assessment as related to professional relevancy (Clouder and Toms 2008; Iannone and Simpson 2013; Joughin 2007; Simper 2010; Singh 2011; Thomas, Raynor, and McKinnon 2014). In these surveys, students consistently view oral examination to be an assessment tool fostering deeper learning, affirming what proponents of experiential learning advocate: dynamic learning experiences which are “structured to require the learner to take initiative, make decisions and be accountable for results.” Indeed, as Joughin and Cantley-Smith summarize, students approach academic tasks according to how they perceive the task will benefit them; thus, if students perceive oral assessment to be more professionally relevant, they are more likely to prepare in more thoughtful ways.

Sample Colloquies and Assessment

To best demonstrate our colloquy methodology, we begin this part of our discussion by highlighting the accomplishments of our culminating second-year students. Our music program has for several years required a music theory proficiency exam at the end of the four-semester sequence. For the first time this year, the proficiency exam was entirely spoken. Thirty minutes prior to their scheduled colloquy time, students picked up a packet of three one-page score excerpts representing different historical style periods. If necessary, the instructors removed surface-level identifying features such as composers’ names and distinguishing titles (e.g. Rite of Spring) from the excerpts. Students were instructed to use the thirty minutes to place the three excerpts in historical order and to consider the likely genre and possible composer of each. But more importantly, they were to prepare discussion points based on the musical evidence within each score to justify their deductions. In essence, the students were asked, “to which style period does each excerpt belong, and how do you know?”—the second part of this question being equally if not more important.

As had been the case across eleven previous colloquies over four semesters, the instructors greeted each student with warm, personal words before prompting the assessment process with a statement reiterating expectations. In particular, we encouraged students to discuss any musical information which they used to determine their answers. For example, if a student found German-language vocal text paired with piano scoring to hint at Romantic-era Lieder, we then expected the student to affirm their assumption by addressing the specific musical concepts at work in the music which more precisely suggested this period and genre. In the case of the particular Lied used for the colloquy—of which we excerpted the final page—we sought confirmation that the student could identify the key, point out periodic phrasing and cycle-of-functions progressions, track modulations to distantly-related keys, and observe the mode mixture, augmented-sixth chords, and other chromatic materials which so distinguish much of Romantic-era Lieder. Students’ preparation for their proficiency colloquy over the preceding four semesters proved invaluable; most of the students adeptly navigated their opening remarks and the question-answer dialogue that followed.

In first-semester colloquies, when analytical questions are far narrower, students’ ability to rationalize their responses remains critical. For instance, one of the simplest and most important questions students must address in their first several colloquies is, “what key are you in, and”—again—“how do you know?” “How do you know?” (i.e. “justify your answer,” “explain further,” “are you sure?”, “what else must you consider?”, etc.) transforms the learning environment from passive to active and compels students to consider context as equally important to content. For example, Colloquy 1 tasks students with engaging melody and phrasing within some exemplar of Classical-era musical clarity, something like Mozart’s aria duet, “La ci darem la mano” from Don Giovanni. Students should derive that the key is A major not simply by considering the key signature, but also by offering notated musical evidence: namely, that Mozart employs the note ‘A’ as a structurally foundational pillar from which and to which the vocals consistently depart and return, and on which they conclude in octaves (note the PACs in measures 8, 18, and 78). In doing so, students demonstrate a primary outcome of Unit 1: an understanding of key and the structural salience of scale-degree 1 in context with Classical-era conventions toward periodic phrasing and global structure.

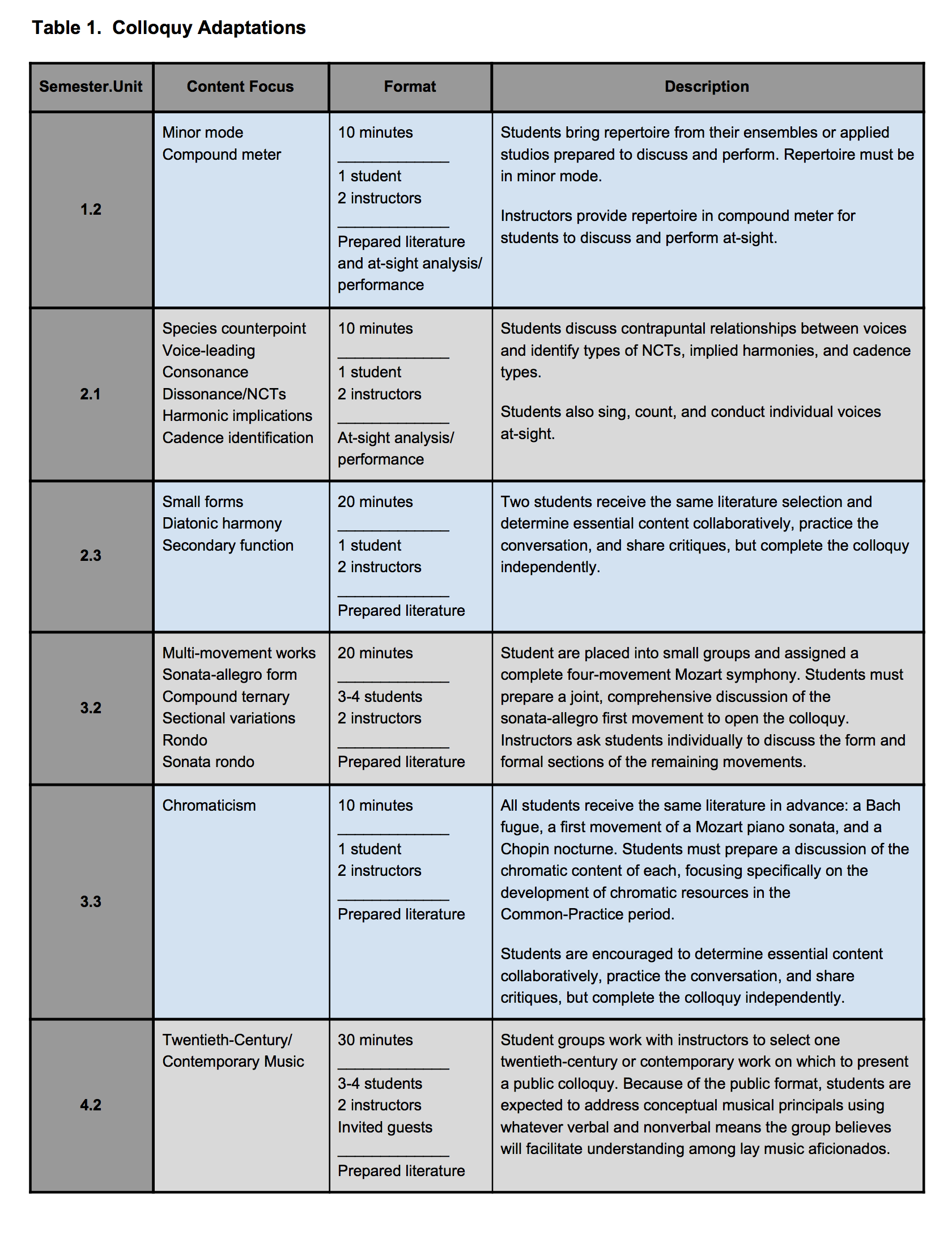

Colloquies assume a variety of formats beyond the initial and the culminating assessments described above. Table 1 briefly samples some of the other colloquies within our four-semester sequence and provides a cursory look at the sequential, progressive nature of the assessments as they occur throughout the curriculum. Timings between colloquies vary, and group and public colloquies offer a welcome alternative to individual assessment. Working primarily from musical scores early and throughout the curriculum imbues it with fluidity; in essence, the content of the musical literature presented within a unit informs the structure the colloquy will take, as the organic nature of discussing different musical phenomena often requires different modes of conversation.

Students prepare for their colloquies in various ways. Most significantly, the day-to-day instructor-led and small-group discussion and performance of musical scores in class provides the foundation for what is expected at the point of assessment. Closer to each colloquy, students prepare through individual written work and peer collaboration. Students complete written Concept Pages in which they identify and notate examples of essential musical concepts from the literature, compose original examples applying said concepts, and write original one-paragraph discussions about each. These Concept Pages go through an editing process that involves both faculty and peer review. Through the process of drafting and editing Concept Pages, students gain a deeper awareness of musical concepts and cultivate the ability to discuss them with clarity and precision. Finally, students prepare collaboratively in a number of ways: they practice with their peers through mock colloquies in and outside class; sometimes, as in Colloquies 2.3, 3.2, and 3.3 detailed in Table 1, students share colloquy repertoire and are encouraged or required to work together to prepare; and occasionally, student partners present on their assigned repertoire to the class to practice the discussion, receive feedback, and build confidence in the process.

Three unit colloquies account for approximately one-third of the final semester average. Each colloquy uses a standardized three-column rubric measuring 1) Content, 2) Delivery, and 3) Performance Craft. Column 1 measures conceptual understanding (“How do you know”), and includes both new material introduced within a unit and previously mastered concepts. Column 3 places conceptual understanding within the realm of performance, as students must sing, count, and conduct passages with rhythmic and pitch integrity. Professional relevancy comes full circle through those aspects of the colloquy measured in Column 2: Delivery. Delivery encompasses appropriate preparation, efficient communication, confident exchanges, attire, and interpersonal demeanor, all of which are generally considered universal soft skills beneficial to success in any profession. The openness of the rubric provides opportunities for personalized assessment. In addition to immediate oral feedback from each instructor within the colloquy, students receive written feedback in the assessment categories and “Suggestions for Improvement” boxes. This written commentary establishes and documents an ongoing formative dialogue between faculty and students. Our students appear to take great pride in their colloquy preparation and, as noted above, faculty colleagues confirm they see transference into other courses, applied lessons, and ensembles.

Concluding Thoughts

Additional benefits of oral examination include facilitating academic integrity, serving diverse student populations (Singh 2011; Symonds 2008), and promoting the upper three strata of Bloom’s taxonomy. Still, the colloquy is greater than a test. We perceive that consistent, face-to-face evaluation coupled with immediate, honest feedback promotes positive and enduring student-mentor cultures. The colloquy is a vehicle through which instructors affirm their investment in each student’s success, and students recognize that instructors are partners in their formative process of becoming professionals. In a larger sense, the colloquy reinforces the significance of university training in a digital age in which knowledge is accessible at rock-bottom prices. For two years, students and faculty peers discuss a shared love–music. As trust evolves, the channel of knowledge transfer widens. The student-mentor relationship lived out in the colloquy validates the students as individuals and enriches instructors’ work as professors.

This work is copyright ⓒ2017 Scott M. Strovas and Ann B. Stutes and licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.