Engaging Students: Essays in Music Pedagogy, vol. 5

Drawing Students In: Using Doodling to Support Engaged Listening

Judith Ofcarcik, Fort Hays State University

Introduction

In the spring of 2016 I participated in the Mindful Drawing Project, an interdisciplinary research project led by two of my colleagues at Fort Hays State University, Amy Schmierbach (art) and Gene Rice (philosophy). Throughout the semester they guided participants through a variety of activities exploring the intersection of mindfulness and creativity. As part of the project we invited Erin Wiersma, professor of art at Kansas State University, to present some of her work and share a favorite drawing activity. She chose to have us draw for over an hour to a single song, played on a loop. We were encouraged to create abstract drawings to reflect what we heard, while focusing on the activity of drawing rather than on the finished product.

Even though I am a professional musician, I was shocked at how easy it was to stay engaged in listening for over an hour. After an initial period of feeling uncomfortable with this new type of listening experience, I settled in and was able to stay focused on the recording for far longer than I would have predicted. Further, I found that I enjoyed having the time to really dig in to what I was hearing and move my attention through different layers of the texture.

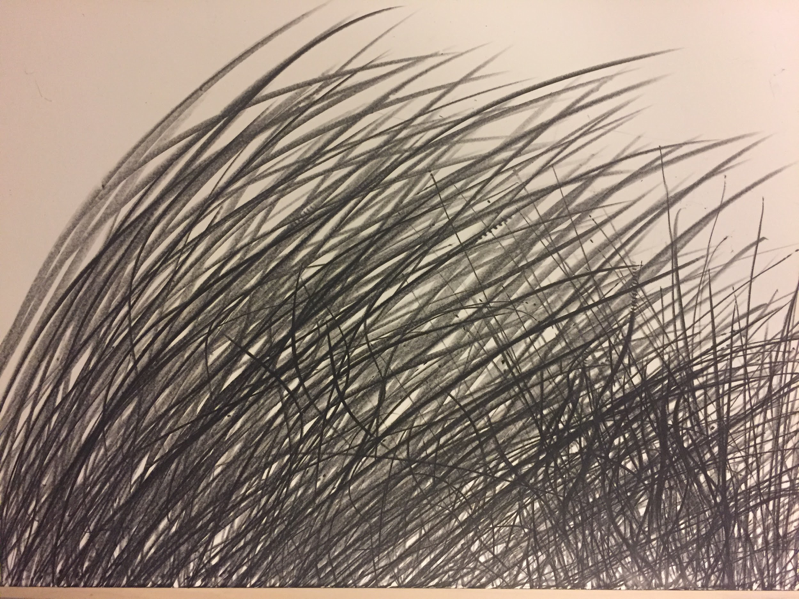

Figure 1. A portion of my completed drawing.

My surprise at my ability to attend to the recording sprang from two sources: First, I had simply never been able to focus so well over such an extended period of time. The fact that the recording we listened to was a single song played on repeat made this feat even more remarkable, as it “should” have felt monotonous and boring. Second, I would have expected that drawing would distract from listening, rather than support it. How did engaging in two simultaneous activities make it easier to focus? Anecdotal evidence from other participants in the Mindful Drawing Project suggested that drawing activities could actually increase environmental awareness, which helped to explain how drawing could help me listen more intently.

The type of abstract drawing I engaged in was more akin to doodling than representational drawing, in both its immediacy and its function: drawing in this activity is used solely to support engaged listening rather than as an end in itself. So, although this particular kind of mark-making requires more attention than mindless doodling, research on doodling can help us understand why this activity encourages focused listening.

Writing specifically about focused listening, Madsen & Geringer (2000/2001) state that “keeping people on task” is the most important element of encouraging meaningful listening in the classroom, and suggest a simple activity of marking beats on paper as they listen as a way to keep students focused. This is similar to the activity Ms. Wiersma presented; however, if students are allowed to decide how best to visually depict the music, doodling could be capable of providing a more robust interpretive experience.

The interaction of doodling and listening are examined further by Jackie Andrade (2009), in which subjects listened to a “boring” voicemail message, with some subjects asked to sit quietly and some subjects given a specific doodling activity to complete. They were then given a surprise quiz that tested their retention of information from the message. Subjects who doodled while listening outperformed their peers who listened while sitting still. Andrade argues that doodling helped concentration, suggesting further that doodling might be particularly helpful with listening tasks, since the physical process of doodling doesn’t interfere with the ability to listen.

Another possible explanation for why doodling might support attentive listening is given by Srini Pillay (2016), suggesting that doodling makes a seemingly too-simple task more demanding, signaling to the brain to increase its focus: “Doodling keeps you from falling asleep, or simply staring blankly when your brain has already turned off. The permission to ‘free-draw’ keeps your brain online just a little while longer.” Upon completion of the activity, I immediately started to think of other repertoires where this activity might help me maintain my aural attention over longer periods of time. I also wondered if there was a way to import drawing into the theory classroom to support students’ focus while listening. When listening to music that involves a process unspooling throughout the work, for instance, missing a single event could result in the student missing the “point” of the piece. Thus, a high level of attention to detail must be maintained over an extended period of time. Muraven and Baumeister (2000) suggest that a challenge to extended listening is vigilance, a type of self-control. Vigilance requires attending to specific events, such as components of musical processes occurring over time. These authors argue that the self-control required for vigilance actually resembles a muscle with resources that are depleted with use. However, a short break can replenish these resources. Perhaps the simultaneous activities of listening and drawing provide the opportunity for the brain to take a short break from one activity by focusing briefly on the other, thus replenishing its resources. For instance, if my attention starts to flag, I can focus on evolving my marks to better reflect the music; my attention is primarily on drawing at this point yet I am still thinking about the music, making it easier to get back on track aurally.

Doodling + listening appears to create a good balance: it is challenging enough to keep the brain turned on, but not so challenging that it forces the brain to decide which activity to attend to. This is another benefit of introducing the activity discussed here as mark-making rather than drawing, as it encourages the students to make smaller, simpler marks that can be replicated over and over rather than a composed, representational drawing which would require more attention.

The Benefits of Doodling for Challenging Repertoires

Minimalist music is one of my favorite repertoires to cover with Theory IV students. Often students enter Theory IV already resistant to twentieth– and twenty-first century music, and many of the standard works from the early twentieth century confirm their bias that this repertoire is strident and difficult for listeners. After a few weeks spent listening to such challenging works, it is a relief for them to switch gears to the soothing sounds of Pärt’s Spiegel im Spiegel or the intense yet accessible progressions of Glass’s Akhnaten. Students are often surprised at how familiar, enjoyable, and immediately beautiful this music is—even though it, too, is from the “dreaded” twentieth century.

However, this corpus has its own pedagogical challenges, the greatest of which in my estimation is maintaining student engagement through these often long and slowly-changing works. Steve Reich’s It’s Gonna Rain is one of my favorite compositions, and students often seem to agree, yet at approximately eighteen minutes in duration it can tax the listeners’ attention span.

Undergraduate students simply do not have much experience with this longer-form listening. Likely the longest works they have heard are from the nineteenth-century symphonic repertoire, yet these pieces typically conform to common-practice genres. Formal functions such as “development” and “recapitulation” provide points of re-orientation should attention wane. Minimalist works lack these features, which can lead some students to simply give up once their attention begins to wander.

If students are struggling to focus while listening to minimalist music, a repertoire that is often more processual than teleological, classroom discussion is severely hampered. Equally distressing, they may miss the opportunity to develop an appreciation for a repertoire that is actually quite accessible and satisfying to the novice listener. In short, my goal when introducing this repertoire is to foster an environment in which students can maintain their aural engagement through the entire length of an extended work, and then participate in a productive discussion.

Recently, I have found success with a particular type of drawing activity—or more accurately, doodling activity—that encourages sustained, focused listening over an extended period of time. Not only have my students reported surprise at the ease with which they could stay on task, discussions after this activity have been much more engaged, as students remember many more musical details. Clearly, they have been processing what they heard even while drawing. Additionally, students can use their finished drawing as a visual map of their experience of the piece, which further assists their discussion.

Activity Details

While this activity can be completed with standard paper and pen or pencil, I prefer to use plastic-coated freezer paper (available at most grocery stores) and china markers (wax pencils that make strong, smooth marks on slick surfaces). There are several benefits to this setup: First, the freezer paper provides the students a larger “canvas” to work with, which is better suited to more extended works. I have found it also helps to reduce any anxiety students feel about their drawing skills by making it clear that they will have plenty of room to experiment and develop their marks. Second, the china markers draw very smoothly and easily, while making a bold mark. Finally, providing “special” materials can jump-start the process of engagement for students by getting them excited about the activity. And although the materials are special, they are not expensive—china markers are available online for less than $1 per pencil and will easily last for more than one class, and the paper is even cheaper, $7 or less for 50 square feet.

When introducing this activity to students, I am careful to present it as “mark-making” (first suggested by art professor Amy Schmierbach) rather than “drawing.” Using this term helps to emphasize to students that creating abstract “marks,” rather than representational drawings, is most helpful for this activity. It also reassures them that they will not be judged on their ability to render accurate or artistic representations of objects or scenes. Ideal markings for this activity can vary widely but smaller elements work best, as they require little to no advance planning and encourage spontaneity while offering students with a safe element to practice improvisation. I typically suggest that students begin with motions that resemble writing, moving left to right across the page, then gradually work to find marks that are more representative of what they are hearing.

After we have finished listening to the piece, I take a few minutes to go around the room, showing each student’s drawing and allowing the class to share how the drawings reflect their aural experience. As the students feel confident that they have truly listened and carefully developed their own visual representation of the piece, they are typically excited to share their drawings, and often point out how their marks shifted over time to better represent the music. They also tend to identify particular locations in their drawing with specific musical events; this demonstrates the utility of the drawings as an aid to memory and discussion. After all of the drawings have been presented, we discuss as a class common themes that emerged. For instance, a particular mark might have been present in more than one drawing, or multiple students might report focusing on the same musical element. In the example I have used most often, from Glass’s Einstein on the Beach, students are often drawn to a sequence of chanted numbers that exhibits a surprising irregularity. I then ask them why that stratum of the texture was so notable, and how it was set apart from the rest of the texture. While this discussion may seem simplistic, even analysis at this level is nearly impossible if they didn’t pay attention to the entire work. It also provides a friendly introduction to a deeper, more active listening experience and more nuanced discussion of the piece.

I like to collect the finished drawings for display, either outside my office or at our end-of-semester honors recital. Students are excited to see their art out in public (although they can opt out of the display if they wish) and it leads to great discussion between students and faculty about Theory IV and minimalist music.

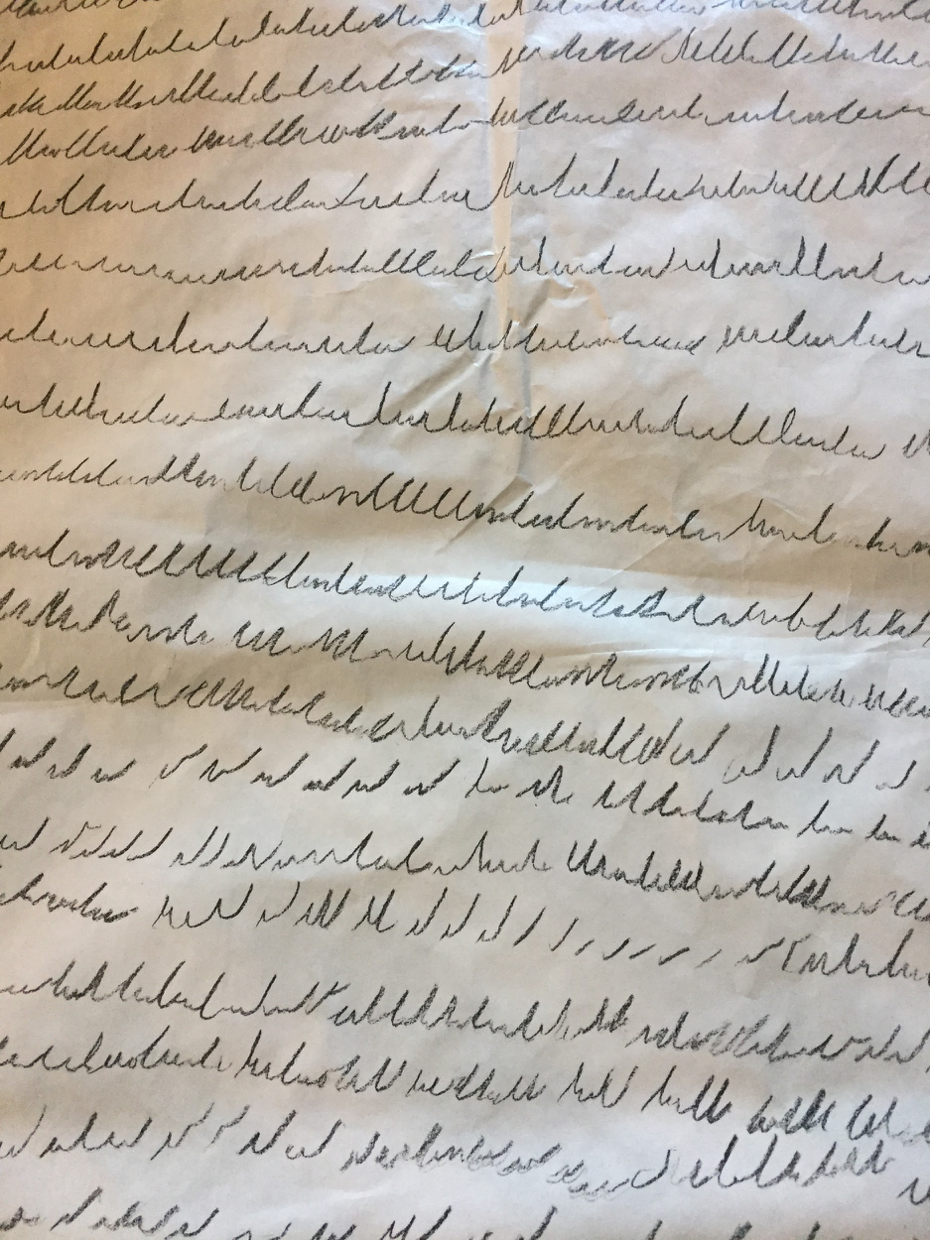

Here is a representative sample of the marks students have developed when listening to Act III, Scene 1: Trial-Prison (Part 2) from Einstein on the Beach.

Figure 2. A representative sample of a complete doodle.

Figure 3. A sample of student work that shows experimentation with mark-making.

Summary

The sheer length of many musical works presents a unique challenge to engagement. By guiding students through a particular type of doodling activity, instructors can encourage meaningful listening and increased recall of musical events to support classroom discussion. While this activity is quite simple, it is supported by recent psychological studies on doodling and attention. It also has the potential for expanded use with any challenging repertoire—after doing this activity with my Theory IV class early in the semester, I noticed an increase in musically-reflective doodling as we moved on to other styles.

It would be interesting to explore more ways of combining the visual and aural domains to keep students on task and support classroom discussion. For instance, there is great analytical benefit to listening to any work more than once, and musically-focused doodling could help sustain engagement over time when listening to a shorter piece on a loop. Students would likely discover more musical details if they listened to a piece several times in a row over a span of twenty minutes before engaging in classroom discussion, particularly if they then had a visual map of the piece to reference as they conversed with their peers.

This is also a fun way to foster interdisciplinary learning. On occasion I have worked with a colleague in the art department to run this activity as a joint class meeting of Theory IV and Drawing III. Students from both classes enjoyed the opportunity to work side by side and we had a particularly interesting conversation about the connection between listening and drawing. Many artists listen to music in a very purposeful way while working, choosing particular works to listen to when working on specific projects, while music students tend to see the two domains as very separate. Talking with their cross-campus peers encouraged my theory students to think more creatively about how musical and visual activities can be combined, and led to continued comments about connections between music and art for the rest of the semester.

This work is copyright ⓒ2017 J. Judith Ofcarcik and licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.