Engaging Students: Essays in Music Pedagogy, vol. 4, Engaging Students Through Jazz

On Using Jazz to Strengthen the Teaching of Rhythm and Meter in the Music Theory Classroom

Margaret Thomas, Connecticut College

“Music is a temporal art form.” Most of us, I suspect, routinely say some variant of this phrase to the students in our undergraduate theory classrooms. And yet, our curriculum tends to favor matters of pitch organization disproportionately over those of temporal organization, a fact that has been recognized as problematic by Richard Cohn, Christopher Hasty, Jonathan Kramer, and Ryan McClelland, among others. In this paper I argue that one way to address this disparity—particularly in the early stages of the undergraduate theory core, when engaging with issues of temporality beyond basic rhythmic and metric concepts can be difficult—is to inject jazz repertoire and practices into the curriculum.

Because jazz usually projects regular underlying metric and phrase structures, using it in the classroom prompts listening and performance activities that reinforce fundamental metric and rhythmic topics. Because we typically listen to jazz without a score, those topics must be confronted both conceptually and aurally. Because jazz performance practice frequently contests the expectations set up by its regular metric structures (Keith Waters), it invites the listener to track musical motion differently than does a performance that aims to adhere precisely to a regular metric framework. And because jazz features unique temporal characteristics such as swing and groove, incorporating it enables us to confront provocative questions of rhythm, meter, and temporality that are not always presented by other repertoire.

There is an important concern that both motivates and challenges my argument: non-jazz players can be intimidated by jazz, and, as a result, struggle with connecting to it as listeners. Lawrence Zbikowski argues that “knowledge structures are used by listeners to guide their understanding of a musical work as it unfolds,” and that “being a member of a musical culture means knowing how to interact with the musics of that culture.” Thus, not only can addressing the temporal aspect of jazz in the core curriculum enhance the way we teach matters of rhythm and meter, but it also can build knowledge structures for non-jazz players, which can facilitate their meaningful interactions with jazz as a repertoire in much the same way that incorporating improvisation and jazz harmonic idioms into the theory core curriculum does, as argued persuasively by Garrett Michaelsen and Michael Palmer.

Listening and entrainment

Regardless of students’ familiarity with jazz, discovering a performance’s rhythmic and metric regularities and irregularities can generate rich interactions with jazz for all listeners. At the beat level jazz musicians often place articulations just ahead of or behind the beat (Matthew Butterfield), while at the division of the beat level eighth notes are commonly performed unequally (“swung”). At all levels—division of the beat through phrase—disruptions and shifts are common, resulting in syncopation, polyrhythm (Cynthia Folio), hemiola, and the like. We can inspire our students to discover these rhythmic practices through a range of active listening exercises. Often, these exercises serve quadruple duty: not only do they reveal aspects of jazz rhythmic practices, but they also expose student deficiencies with rhythmic fundamentals, provide a means to improve facility with those fundamentals, and introduce higher-order concepts related to music’s temporality.

Reinforcing the concept of metric regularity through conducting in class—something that most of us do routinely—is an example of one such multipurpose exercise. While most students can “count” by the time they arrive in our classrooms, many are surprised when we ask them to conduct while singing or speaking rhythms. Conducting can reveal students to have less fluency with counting than they claim, along with an unfamiliarity with the notions of metric hierarchy and musical motion. I employ a hybrid form of “tapping-conducting” to encourage not only the development of steady conducting patterns but also to force a physical synchronization with heard pulses: students begin by tapping beats as they listen, and then they organize the beats by superimposing a relevant conducting pattern onto the tapping. Once established, tapping-conducting becomes a vehicle for improving both pulse steadiness and the expression of metric hierarchy in student performances.

When we pair conducting or tapping-conducting with listening in the classroom, it becomes a communal form of entrainment, which Justin London describes as “a synchronization of some aspect of our biological activity with regularly recurring events in the environment.” As London says, “metric attending involves both the discovery of temporal invariants in the music and the projection of temporal invariants onto the music.” Conducting can be the physical conduit of those invariants, and it also serves as a critical point of reference for comprehending deviations from temporal invariants; in other words, it helps students to discover jazz rhythmic practices. Having such a point of reference is especially critical when listening without a score, as we do with most jazz.

Musical examples that are familiar to many students (“Take the ‘A’ Train,” “I Got Rhythm,” and the like) can serve as both alluring and useful starting points for the work of tapping-conducting while listening. Depending on the piece and particular performance, this exercise can segue into the discovery of the presence of particular jazz rhythmic practices, including back beat, swing, stop time, half time, and double time. It also enables the discovery of rhythmic practices that span genres, including rubato and hemiola. This kind of active listening is useful not only at the level of the musical surface, but also with a broader perspective. Once the surface meter is established among the students via tapping-conducting, I then challenge them to “explode” their conducting, organizing half measures, full measures, pairs of measures, and so on, with successively slower conducting patterns. Because phrase rhythm tends to be quite regular in jazz (four-bar units and multiples of four bars are the norm), exploded conducting is especially effective in this context. It can be used to introduce the concept of hypermeter, to track formal structures (more on that below), and to facilitate attentive listening.

Sound and notation

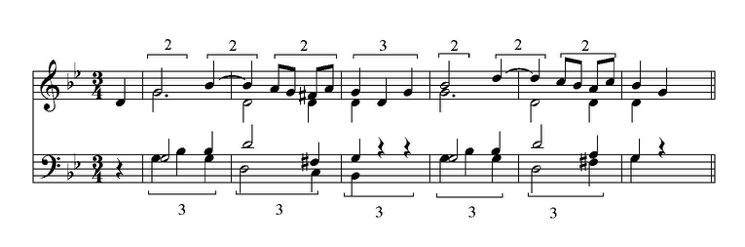

Working without a score as I describe above can be challenging and even unsettling to students, especially those who are accustomed to confirming what they hear by consulting a score. While lead sheets (abbreviated scores) are available for many jazz tunes in such sources as The Real Book, there are many aspects of a performance that are not represented by a lead sheet. To explore the extent to which notation reveals temporal structures, we might pair listening to the third movement of Mozart’s Symphony No. 40 with Thelonious Monk’s “Straight, No Chaser.” Both prominently employ hemiola and metric displacement at the outset, techniques that—once heard—can be confirmed through an examination of the score and lead sheet. The conflicting 2- and 3-beat layers are easily discovered in the Mozart score (piano reduction), as I show here with brackets:

Figure 1. Mozart, Symphony No. 40, mvt. 3: brackets delineate the conflicting 2- and 3-beat layers.

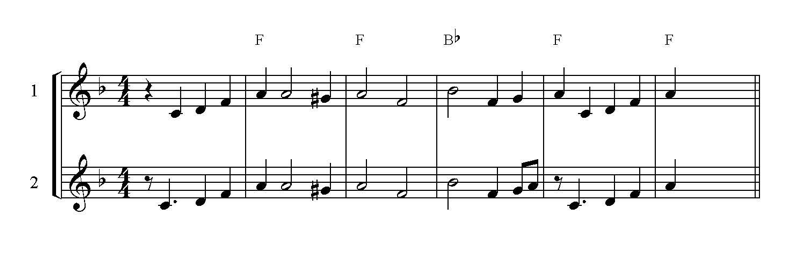

The metric displacement in “Straight, No Chaser,” which results from the manipulation of the primary motive, is similarly discoverable in its lead sheet, assuming that the F–B♭ gesture projects an anacrusis-downbeat structure each time it appears (I show this with brackets below). The relationship of the irregular melodic line to other musical layers in a given performance is not clearly observable in the lead sheet, however, aside from the shifting alignment of the primary motive against the harmony.

Figure 2. Thelonious Monk, “Straight, No Chaser”: brackets delineate the recurring primary motive.

Thus, examining the lead sheet for “Straight, No Chaser” provides a useful first step toward understanding the tune’s temporal fabric, but it compels further engaged listening. Depending on the level of the students—and on the particular performance listened to—we might tackle such questions as: why we hear this in 4/4 given the melodic irregularities, what Monk does with his left hand to support or complicate our hearing of the meter, and what the other players are contributing to the rhythmic/metric scheme.

Not only can a lead sheet be used to confirm what is heard in a recording, but it can be a guide for listening to entire performances—a “road map,” to use Brian Alegant’s term. Especially for non-jazz players, keeping track of where a performance is relative to the lead sheet encourages engaged listening. And this form of engaged listening supports an awareness of the large-scale, cyclic temporal flow intrinsic to most jazz performances. Each statement of a chorus is analogous to an exaggerated hypermeasure in that it is a “recurring metrical unit” (Stefan Love), a fact that can drive our pedagogy. Once students learn a work’s schema with the aid of the lead-sheet-as-road-map (its harmonic progression and form), they are better able to track the schema as a recurring unit, recognizing the beginning of each chorus as a hyper-downbeat. Eventually this tracking can take place aurally (without the lead sheet), thus providing non-jazz students with another entry point to jazz culture insofar as this listening experience mimics the performance experience of cycling through a form.

Working with lead sheets profitably takes place collaboratively: in pairs, students listen to a recording, with one conducting and tracking the progress within the form while the other annotates the lead sheet in response to prompts that reflect the instructor’s pedagogical aims. Alternatively, this exercise may be completed using Audacity, for which students can work alone or in pairs to annotate the audio file. In any case—in pairs or alone, on paper or electronically—this exercise challenges students to recognize the form, its repetitions, and deviations from it. In the early stages annotations might simply track the number of repetitions of the form, with brief descriptions (“3rd time = trumpet solo,” for example).

As students become more experienced, annotations may reflect phrase and hypermetrical structures, rhythmic alterations, anticipating or delaying beats, swinging eighths, tempo alterations, moments of hemiola, changes in the timekeeping pattern of the rhythm section, polyrhythm, and so on. The lead sheet can be a useful guide for comparing different performances of the same tune, as well, perhaps focusing initially on just the initial statement of the melody. Comparing various performances of “Straight, No Chaser,” for example, including several by Monk and versions by Miles Davis, Gerry Mulligan, Gil Evans, and others, would invite a discussion of the act of interpretation and the inherent imprecision of rhythmic notation, an issue that spans genres.

Enactment

The lead sheet exercises described above naturally segue into transcription work, which requires a keen awareness of rhythm and meter. Moreover, because it is cognitively close in nature to performance, it provides a bridge between sound and notation complementary to that of listening while following a lead sheet. Transcription can begin modestly, perhaps with a straightforward tune like Horace Silver’s “The Preacher.” After listening to the opening a few times the students are asked to refine an instructor-made, simplified lead sheet (version 1 below) so that it more closely matches the recording. Then the students are shown a standard lead-sheet version of “The Preacher” (version 2 below), which captures beat anticipations more accurately than the simplified version, but possibly not as well as the students’ listening-based versions.

Figure 3. Horace Silver, “The Preacher:” 1) simplified version with regularized rhythms; 2) standard lead-sheet version with beat anticipations.

Refining notation to more closely match a performance in this way reinforces the idea that rhythmic notation represents an approximation of events in time, despite how precise it appears to be on the page and in the proportional relationships of whole, half, quarter, and eighth notes. This approximation may be more obvious when listening to (or trying to capture) the rhythms of jazz, especially in light of swung eighths and anticipating and delaying beats, but recognizing it can open a broader conversation about the fuzzy nature of rhythmic notation even in detailed scores of common-practice repertoire, which generally suggest metronomic performances that do not materialize.

Transcription work can also provoke performance activities in the theory classroom, in a number of interesting ways. Recreating and transcribing typical drum patterns is a good first step. For the opening of “The Preacher,” for example, after completing the work with the opening melody described above, the students could focus on the drums and bass, and expand their refined score to include the rhythmic patterns of those instruments, thereby capturing the fuller texture. Students can work individually to transcribe a work’s rhythmic fabric, but this activity lends itself particularly well to small group work: students listen repeatedly to the excerpt while entraining, and then work toward recreating the rhythmic patterns while tapping/conducting (speaking the rhythms works well for this). Once they can recreate the patterns, I have them generate a score (usually non-pitched) that captures what they hear. The web-based notation program Noteflight facilitates collaborative notation quite well. I encourage students to think of these scores as performance scores designed to elicit a convincing rendition of what they hear in the recording, when performed by others. In fact, I typically have small groups exchange the performance scores they create for this very purpose, and their performances not only reveal the accuracy of the transcription, but also provide a vehicle for experiencing a typical jazz rhythmic framework. In creating the performance scores students must confront issues of swing and how best to capture it notationally, along with the beat anticipations and delays that are frequently heard in jazz.

This sort of work can range from quite simple for introductory courses to quite challenging, depending on the complexity of the piece, the performance, and the length of the excerpt (consider Silver’s “The Preacher,” Herbie Hancock’s “Watermelon Man,” and Lee Morgan’s “Gary’s Notebook” as examples with varying degrees of challenge). Creating rhythmic performance scores uniquely encourages hearing and experiencing the concept of groove, which, as described by William Bauer, is “a complex rhythmic phenomenon that results from the musicians’ interactions with the temporal hierarchy and its various levels. An effective groove facilitates our embodied entrainment with the music, and promotes particular qualities of bodily movement.”

Conclusions

In the introduction to this essay I mentioned that non-jazz players may feel intimidated by jazz. This, of course, can be true of faculty as well as students, since many of us were trained in the classical tradition, but it need not prevent us from incorporating the kinds of classroom activities I describe here. Introductory jazz history texts such as those by Mark Gridley, Gary Giddins and Scott DeVeaux, or Henry Martin and Keith Waters include detailed listening guides for particular pieces; the guides are useful starting points for introducing repertoire into the classroom, and they can serve as road maps of a sort for the instructor. Introductory jazz theory texts such as those by Mark Levine and Dariusz Terefenko are equally valuable resources.

There are ways of musical thinking that are particular to jazz players. There are musical behaviors and experiences that are not available to non-jazz performers without some kind of intervention. The pedagogical adjustments that I present here can help all students engage with music’s temporal nature, particularly by having students work without reference to an authoritative score. In addition, incorporating activities designed to help non-jazz students understand and experience rhythmic structures common in jazz will open up that repertoire to them. My primary goals for all students in developing this approach are simple, yet essential: count well, steadily, and consistently; recognize musical events that contradict the underlying isochronous pulses, metric hierarchy, or normative structures; increase the capacity for musical memory and tracking; build knowledge structures to enable meaningful interactions with jazz; entrain effectively to meter; and better appreciate music as a temporal art form.

This work is copyright ⓒ2016 Margaret Thomas and licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution–ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.