Engaging Students: Essays in Music Pedagogy, vol. 4, Engaging Students Through Jazz

Fin de Siècle Harmony – A Jazz Perspective

Dariusz Terefenko, Eastman School of Music

Introduction

The fin de siècle period saw a rapid expansion of harmonic syntax, particularly in the domain of extended chromaticism and chromatic key relations (Daniel Harrison, Richard Cohn, David Kopp, Steven Rings). The shift toward bolder chromaticism and distant tonal relationships manifested itself in the works of various composers, such as Franz Liszt, Hugo Wolf, Johannes Brahms, Cesar Franck, and others. The music of the next generation of composers (such as Claude Debussy, Richard Strauss, Alban Berg, and Maurice Ravel) ushered in even more stunning changes in the realm of chromatic harmony, pushing it further toward its absolute tonal limits. In undergraduate theory curricula, the works of these composers typically appear in the final or penultimate semester of theory instruction, yet their dense harmonic textures, unusual chord progressions, and ambiguous functionality make it challenging for the students to analyze and understand.

Studying the music of the fin de siècle period offers an excellent opportunity to familiarize students with various topics borrowed from jazz theory, such as jazz harmony (Keith Waters, Steven Larson, Mark Levine, George Russell, and Bill Dobbins). The chief characteristic of jazz harmony is the emphasis on larger chord structures, wherein combinations of diatonic and/or chromatic extensions expand the pitch content of chords. Another feature of jazz harmony ― one that stands in stark contrast with common-practice tonality and harmony ― is a considerably different status and functionality of seventh chords (major, minor, major-minor seventh, half-diminished, and diminished). This essay engages its readers in a study of extended chromatic harmony from the fin de siècle period as experienced through the prism of jazz harmony.

Theoretical Background

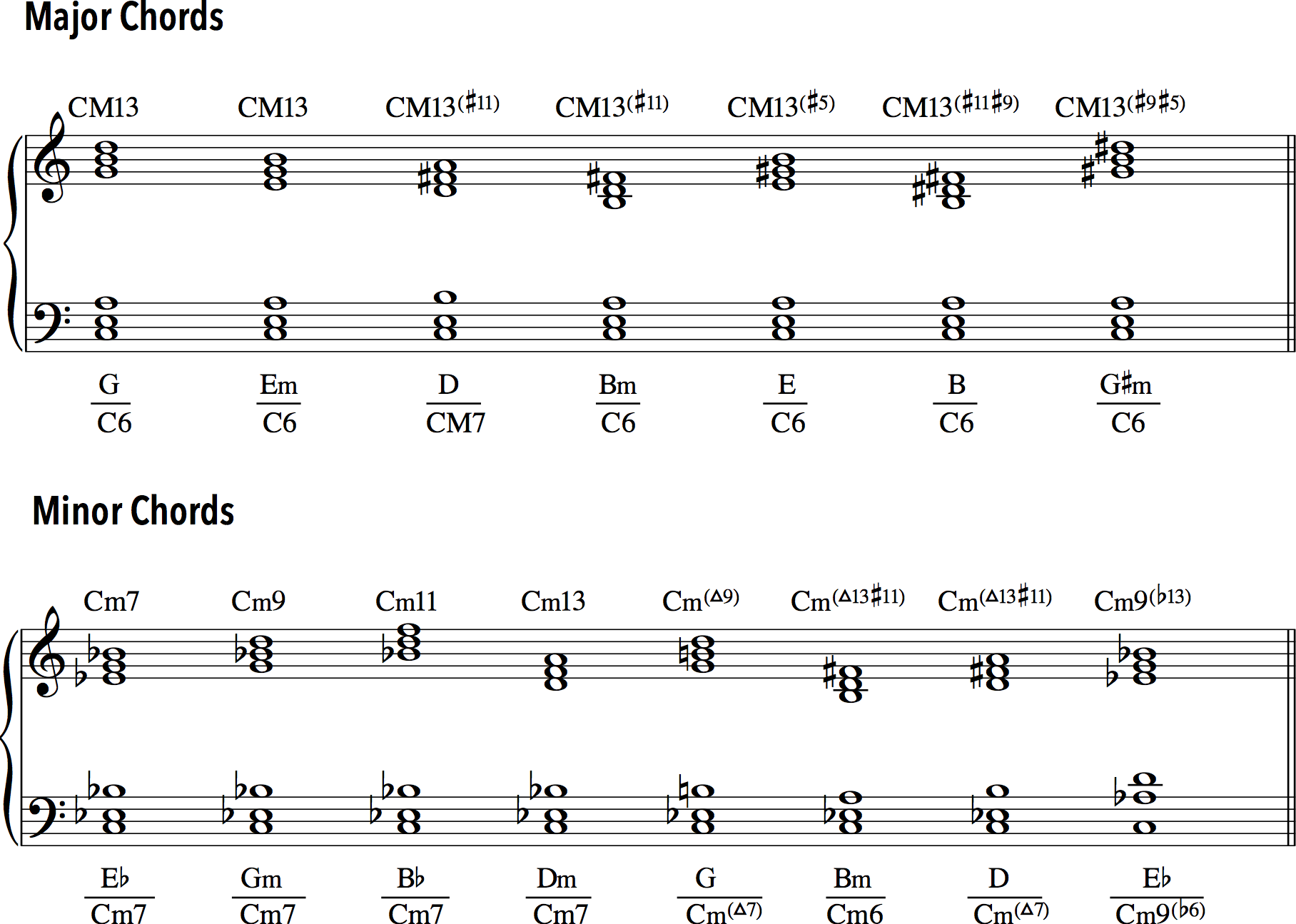

Jazz harmony is fundamentally built from four-part chords. Created by adding a chordal seventh or sixth to a major, minor, diminished, augmented, or suspended triad, these sonorities can appear in various forms, such as: (1) independent formations, (2) incomplete and rootless voicings, and (3) upper structures of larger polychordal units. The addition of chordal extensions (ninths, elevenths, and thirteenths) expands the tertian architecture of four-part chords. The ninth has three distinct forms: a diatonic major ninth, a chromatic flat ninth, and a chromatic sharp ninth. The eleventh has two forms: a diatonic perfect eleventh and a chromatic sharp eleventh. The thirteenth has two forms: a diatonic major thirteenth and a chromatic flat thirteenth. The use of diatonic and/or chromatic extensions, as well as pitch alterations (♭5 and/or ♯5), fundamentally changes the structure of extended harmonic formations.

Broadly speaking, the addition of diatonic extensions enhances the sound of individual chords, while the addition of chromatic extensions generally modifies the sound of chords and renders them harmonically less stable. As such, chromatic extensions are handled with more caution and their treatment resembles that of suspensions in common-practice music, which involves: (1) consonant preparation on a weak beat, (2) dissonant suspension on a strong beat, and (3) consonant resolution. With these preliminary observations in mind, let’s examine how the structure of four-part chords can be expanded using diatonic and chromatic extensions.

The table in Figure 1 summarizes the distribution of chord tones, pitch alterations, and diatonic and chromatic extensions in six types of chords: major, minor, major-minor seventh, suspended, half-diminished, and diminished. (The bold face numbers in the “Chord Tones” column indicate the members of the triad; the italics indicate that either 6, 7, ♭7, or ♭♭7 is added to the specific triad thus expanding it into a four-part structure.)

Figure 1. Chord Tones, Pitch Alterations and Extensions

| Chord Type | Chord Tones | Pitch Alterations | Diatonic Extensions | Chromatic Extensions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Major | 1, 3, 5, 6, 7 | ♭5, ♯5 | 9, 13 | ♯11, ♯9 |

| Minor | 1, ♭3, 5, 6, ♭7 | ♯7 | 9, 11, 13 | ♯11, ♭13 |

| Major-minor 7th | 1, 3, 5, ♭7 | ♭5, ♯5 | 9, 13 | ♭9, ♯9, ♯11, ♭13 |

| Suspended | 1, 4 (11), 5, ♭7 | ♭5 | 9, 13 | ♭9, ♯9, ♭13 |

| Half-diminished | 1, ♭3, ♭5, ♭7 | 9, 11, 13 | ♭13 | |

| Diminished | 1, ♭3, ♭5, ♭♭7 | ♯7 | 9, 11, ♭13 |

This table illustrates most of the possible additions to different chord types in terms of pitch alterations and chordal extensions. To guarantee that their various combinations result in coherent harmonic formations, jazz musicians frequently employ the concept of upper-structure triads. The use of upper-structure triads involves the superimposition of major or minor triads on top of (1) single notes, (2) thirds and sevenths of the underlying chords, (3) other triads, and (4) intervallic structures. To notate these chords, the slash notation is implemented, which makes them relatively easy to interpret and realize. A diagonal slash indicates that an upper-structure triad (notated on the left side of the slash) is superimposed over a single bass note; a horizontal slash indicates that an upper-structure triad (written on top) is superimposed over a chord written below the slash.

Figure 2 illustrates the superimposition of upper-structure triads in the context of major- and minor-type chords.

Figure 2. Upper-Structure Triads — Major- and Minor-Type Chords

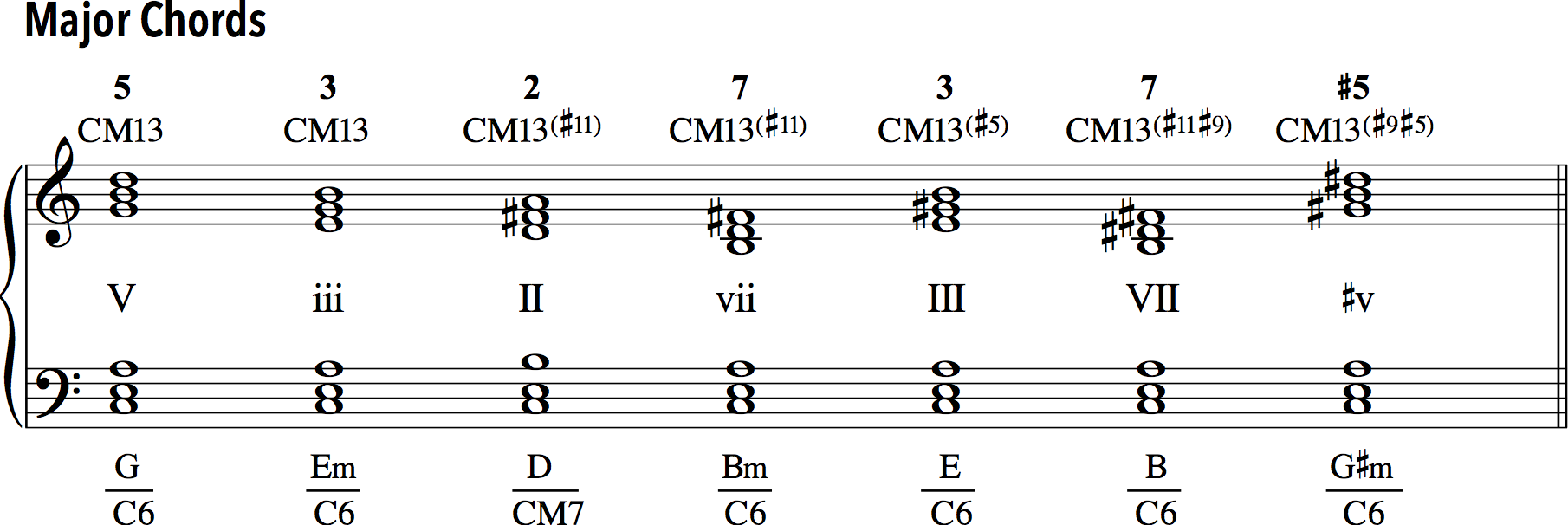

The relationship between the root of the major, minor and major-minor seventh chord, and the root of the upper structure is examined using bold Arabic numbers. Major upper structures are notated with upper-case Roman numerals, which relate to the local chordal root: II on 2, V on 5, ♭III on ♭3, etc. For instance, a B♭ major triad in the context of Gm7 is notated as ♭III on ♭3, yet the same triad in the context of E7 is notated as bV on ♭5 (or ♯IV on ♯4). Minor upper structures are notated using lower-case Roman numerals with relation to the local chordal root: ii on 2, ♭ii on ♭2, ♭iii on ♭3, v on 5, etc. For instance, an A minor triad in the context on Gm7 is notated as ii on 2, and the same triad in the context on C7 is notated as vi on 6.

In the case of major chords, shown in Figure 2a, there are four major upper-structure triads built on local 2, 3, 5 and 7.

Figure 2a. Major Chords — Placement of Upper-Structure Triads

The order in which these voicings appear represents a hierarchy that exists between them. Although a matter of personal perception and preference, this hierarchy refers to the degree of tension that each voicing projects and stems from the saturation of extensions and/or pitch alterations within each chord. In addition to four major triads, there are three minor upper-structure triads built on 3, 7, and ♯5. In the case of minor chords, given in Figure 2b, there are four major upper-structure triads built on ♭3, ♭7, 5 and 2, and three minor upper-structure triads built on 5, 2, and ♯7.

Figure 2b. Minor Chords — Placement of Upper-Structure Triads

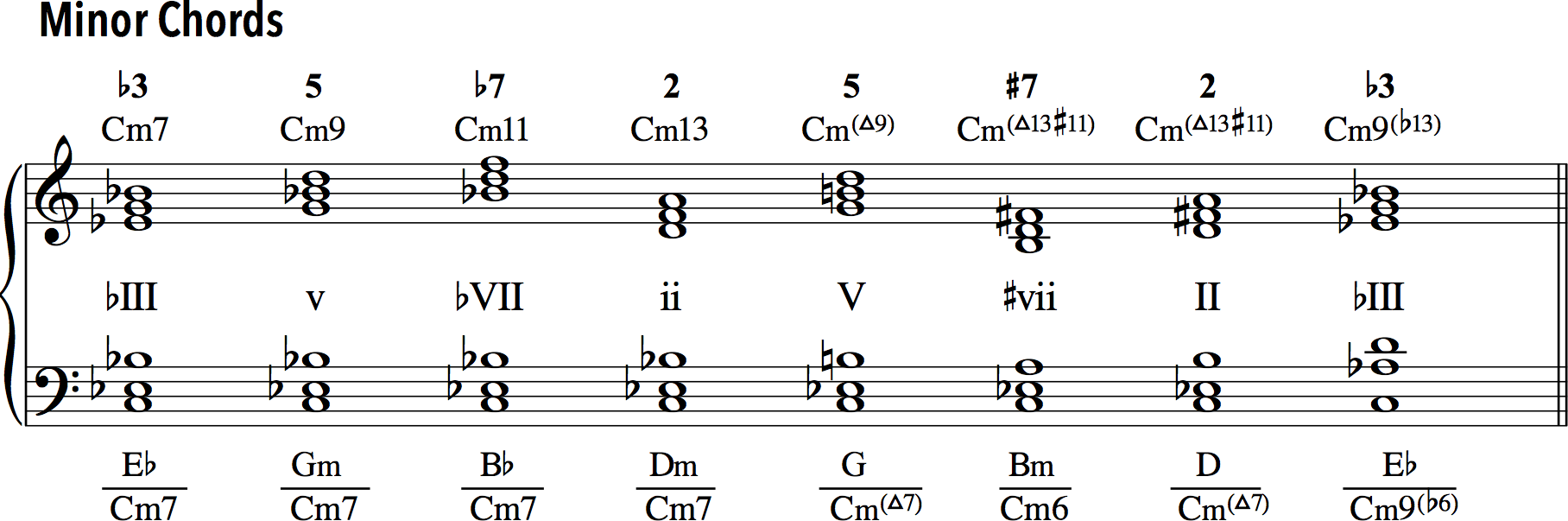

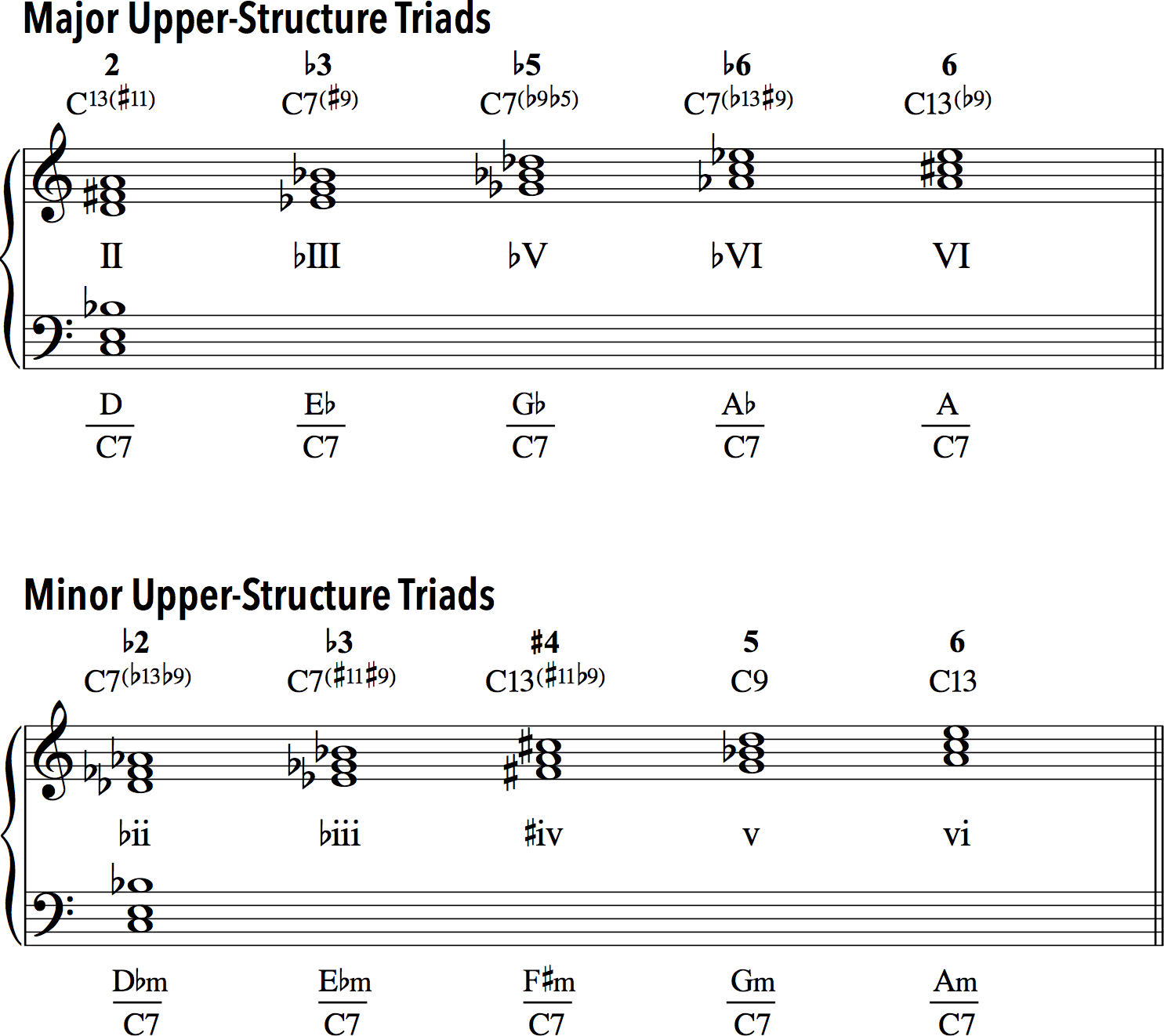

Figure 3 demonstrates the distribution of major and minor upper-structure triads in the context of C7.

Figure 3. Major-Minor 7th Chords — Upper-Structure Triads

Broadly speaking, there are five major and five minor upper-structure triads that can be superimposed on top of the major-minor seventh chord. The reason for this stems from the specific pitch combinations that these triads create and voice-leading behaviors that the participating extensions/alterations project. The major upper structures are built on 2, ♭3, ♭5 (♯4), ♭6, and 6. In addition to five major triads, there are five minor upper structures built on ♭2, ♭3, ♭5 (♯4), 5, and 6, which produce different pairings of allowable extensions and/or pitch alterations.

Practical Applications

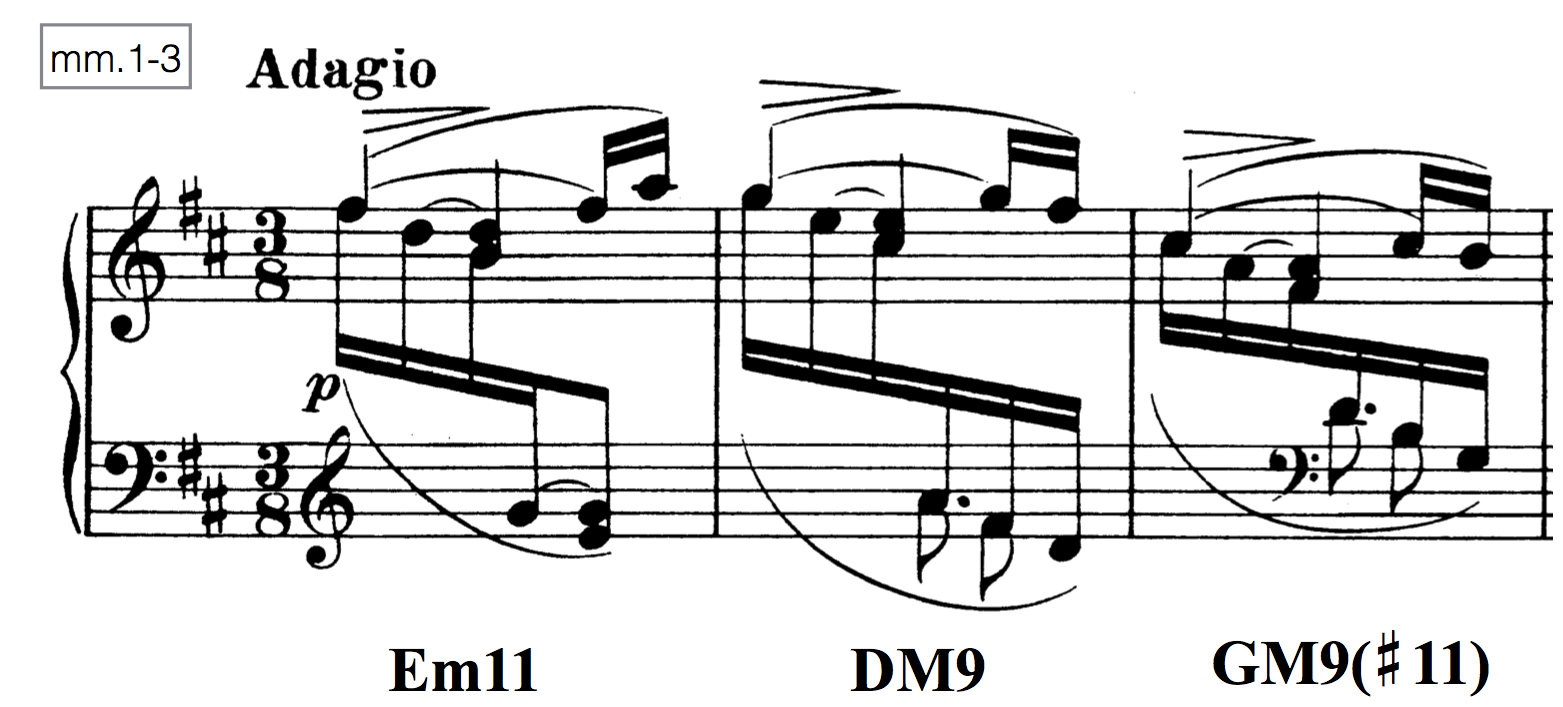

Figure 4 illustrates mm. 1–3 of Intermezzo No. 1, Op. 119 by Johannes Brahms.

Figure 4. Johannes Brahms, Intermezzo No. 1, Op. 119

In the theory classroom, this off-tonic beginning is usually described as an example of harmonic/functional ambiguity, auxiliary cadence, and the free use of non-harmonic tones and appoggiaturas effectively disguising the underlying triadic framework. The recognition of diatonic/chromatic extensions and upper-structure triads in larger harmonic formations, such as those in Figure 4, allows the student to understand their pitch content in a similar way to how jazz theorists perceive individual chords. The verticalization of all the pitches in mm. 1–3 reveals that each measure contains an extended chord that is typical of jazz syntax: m. 1 – Em11, m. 2 – DM9, and m. 3 – GM9(♯11). The G5 in m. 2 cannot be explained in terms of available extensions and, therefore, it functions as a neighbor tone connecting the two F♯5s in mm. 1 and 2. What is particularly interesting about the GM9(♯11) chord in m. 3 is that this formation contains the six pitches (G, A, B, C♯, D, F♯) from the corresponding G Lydian mode. These types of extended formations that establish a convincing relationship with the underlying scales (i.e. chord-scale theory) were quite common in jazz during the modal period in the late 1950s and the post-bop period in the 1960s and beyond.

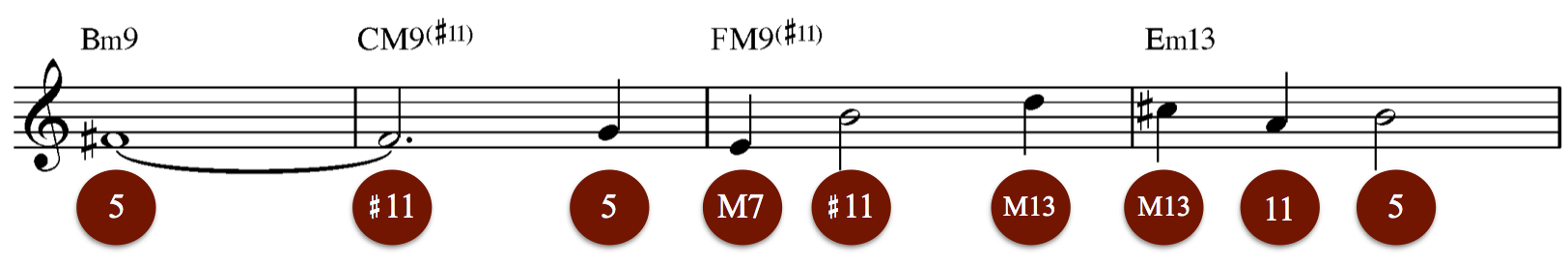

Figure 5 illustrates mm. 1–4 of Time Remembered by Bill Evans.

Figure 5. Bill Evans, “Time Remembered”

This excerpt is notated in the form of a lead sheet and contains the melody accompanied by chord changes. The analysis of the melody reveals some similarities with the Brahms excerpt. For instance, the melodic content in m. 3 in Figure 5 and in m. 3 in Figure 4 is derived from the corresponding Lydian mode. Unlike GM9(♯11) in the Brahms example, the FM13(♯11) chord in the Evans example includes the major thirteenth (D5) and makes the chord fully extended and its pitch content derived from the complete Lydian mode (counting the notes comprising a realization of FM13(♯11)). The initial F♯4 in Figure 5 morphs from the diatonic fifth of Bm9 to the chromatic ♯eleventh of CM7(♯11). That transformation influences the melodic content of mm. 3–4, where each note (with the exception of B4 in m. 4) can be explained in terms of chordal extensions: m. 3 – E4–B4–D5 as major seventh, ♯eleventh, major thirteenth, and m. 4 – C♯5–A4–B4 as major thirteenth, perfect eleventh, and perfect fifth, respectively. Such an accumulation of higher extensions within chords influences the overall character of the melody and our perception of it.

Figure 6 illustrates mm. 13–20 from Part VIII of Valses nobles et sentimentales by Maurice Ravel.

Figure 6. Maurice Ravel, Valses nobles et sentimentales, Part VIII

Ravel’s composition is a model example of the use of extended/chromatic harmony. Extended formations permeate the harmonic palette of the entire piece, yet Epilogue offers a succinct summary of all his favorite harmonic devices, including an array of upper-structure triads and various combinations of diatonic/chromatic extensions effectively expanding the structure of participating chords. Measures 13–20 prolong the dominant seventh harmony on F♯. In mm. 13–16, the two upper-structure triads built on ♭5 and ♭6 (C and D) expand F♯7. In mm. 18–19, the triadic architecture in upper parts is replaced with pairs of extensions: G–D♯ (♭9–13) in m. 18 and G–D (♭9–♭13) in m. 19, before resolving to the local tonic, B(add2), in m. 20. Notice the preparation and voice-leading propensities of the individual extensions: the diatonic major thirteenth in m. 18 prepares the chromatic flat thirteenth before resolving to C♯ (added second) in m. 20.

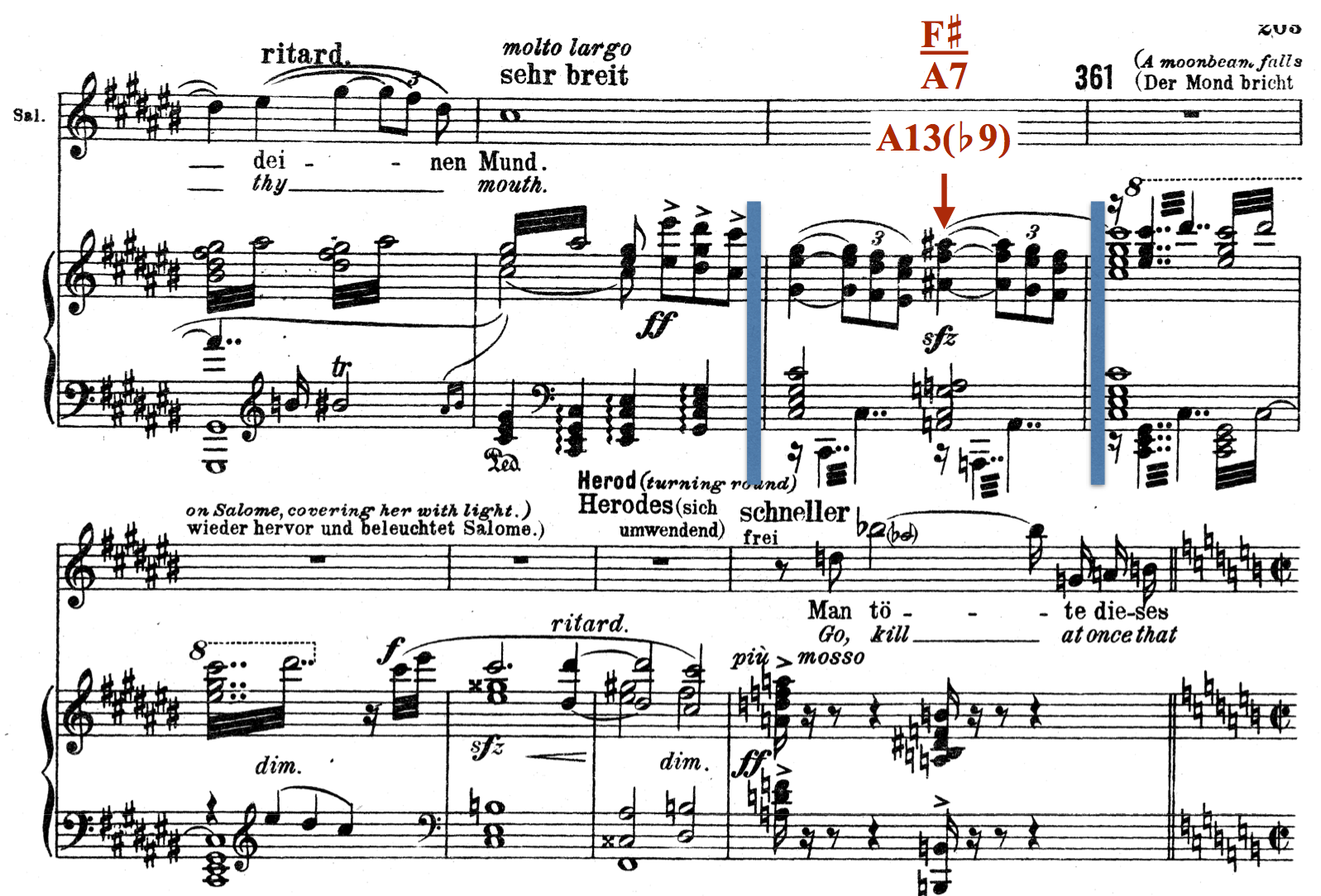

A more complex example of the use of upper-structure triad occurs at the end of Salome by Richard Strauss, where a transformed plagal cadence is saturated with disturbing chromaticism suitable for the macabre conclusion of the opera. Figure 7 illustrates that progression.

Figure 7. Richard Strauss, Salome

The chord built on scale-degree ♭6 has a major-minor seventh quality and highlights the plagal leading tone, scale-degree 6, supported with the F♯ major triad superimposed over A7. In this difficult musical passage, A13(♭9) in m. 360 corresponds to the dominant seventh from Figure 3 but notice how it is not used in a traditional manner.

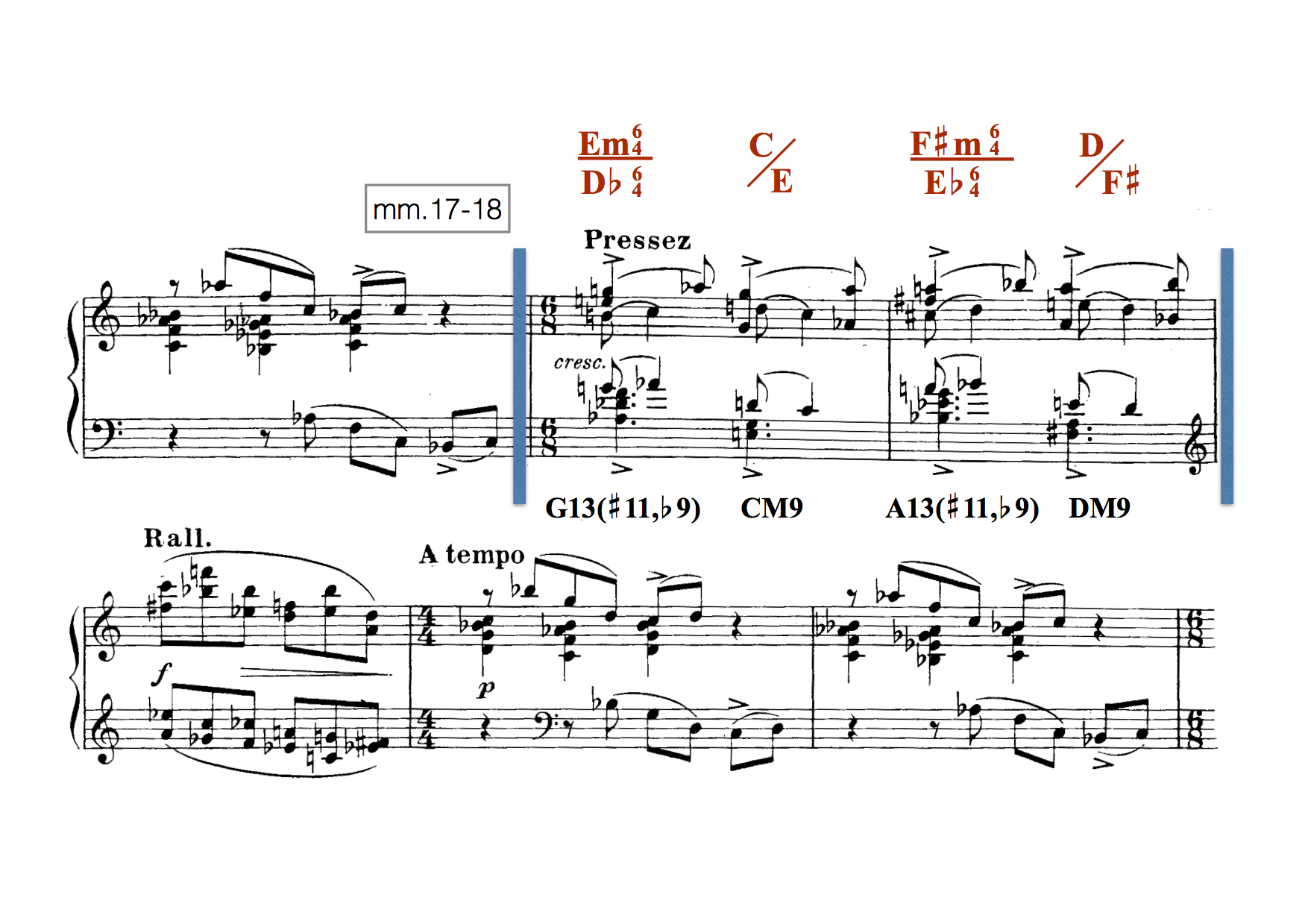

The musical examples discussed thus far have featured chords with clearly articulated chordal roots in the lowest voice. A far more challenging situation arises when the chordal root is implied, disguised or omitted from the chord’s structure. Figure 8 illustrates mm.17–18 from VII Plainte calme by Olivier Messiaen.

Figure 8. Olivier Messiaen, VII Plainte calme

The lowest voice |A♭3–E3| B♭3–F♯3| neither explains the structure nor the functionality of underlying chords, yet the perception of this progression suggests a hierarchical dependence between the two chords wherein the first chord in each measure is more chromatic than the second chord. The analysis of chords occurring on the downbeats of m. 17 and m. 18 reveals the use of two triadic formations: Em6–4 over D♭6–4 and F♯m6–4 over E♭6–4, respectively. Known as polychords, these formations resolve to the first inversion C and D triads decorated with melodic appoggiaturas, D5/D4 in m. 17 and E5/E4 in m. 18. Their resolutions, therefore, imply the presence of some kind of local dominant seventh chords on G and A, which can be alternatively notated as G13(♯11,♭9) and A13(♯11,♭9), respectively. With their roots disguised in the inner voices, these structures are more challenging to analyze, yet the context in which they appear confirms their latent functional status, at least as perceived by jazz theorists.

Conclusion

Utilizing tools from jazz theory in analysis of extended harmonic formations allows students to facilitate their understanding of the complex musical repertory from the fin de siècle period. In addition, it gives them an opportunity to experience harmony in much the same way as jazz musicians do. Engaging students in different modes of analysis, as demonstrated in this essay, has its advantages as it broadens their musical horizons, enhances their musical comprehension, and makes the overall pedagogy more effective.

This work is copyright ⓒ2016 Dariusz Terefenko and licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution–ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.