Engaging Students: Essays in Music Pedagogy, vol. 4, Engaging Students Through Jazz

Strange Changes

Chris Stover, The New School

A central aspect of jazz practice is harmonic substitution, where a functionally related chord of a different flavor displaces, or is superimposed upon, another. These substitutions can be predetermined, as in an arrangement of a jazz standard, or effected “in the heat of the moment,” as ensemble members carve alternative harmonic paths through the “changes” of the tune. Aspects of harmonic substitution, or reharmonization, are addressed elsewhere in this issue. In this essay I will outline a related and, I suggest, foundational practice that can be used as a model for thinking about harmonic substitution: a number of common harmonic progressions built into the structure of the tunes themselves. In other words, the very notion of carving alternative paths toward harmonic goals is already built into the structure of the songs being elaborated upon by jazz musicians. These practices relate to and extend the concept of mode mixture, well-known in conventional music-theoretical discourse.

How might music theory students use an expanded awareness of harmonic possibilities such as can be gleaned from the study of jazz standards, in order to embrace, conceptualize, and apply harmonic substitution, whether working from a prototypical harmonic progression or even from a melody with no predetermined harmonic support? First, mode mixture provides a good entry point for thinking about harmonic substitution: major/minor borrowings are commonplace in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century concert music, and are used for many of the same expressive reasons. Their pervasive use in the American Popular Songbook provides a wealth of examples for a theory instructor to draw upon and for students to engage. Second, as we shall see below, aspects of the way mode mixture is used and extended in jazz allow us to think about harmonic function as a process within which we can locate a number of harmonic objects that can equally fulfill some given function. For example, “dominant function” can be fulfilled by V and viio, but also by ♭II, ♭VII, and even III. This allows us to orient classroom activities toward thinking about what some musical passage is doing, and how it is doing it, rather than focusing primarily on the behavior of a specific chord in fulfilling a specific task. And third, by considering the relatively wide range of chords that emerges from these two considerations, we can imagine some creative classroom assignments where a variety of paths can be selected in order to solve some compositional problem.

Major to minor (and back)

The title of this essay is a play on a famous line from Cole Porter’s “Ev’ry Time We Say Goodbye,” shown in Figure 1. When Porter wrote “But how strange the change from major to minor,” he was channeling a venerated practice of equating major and minor harmony with differently directed emotional states. Specifically, he was reinforcing a mood shift on the part of the song’s narrator, as tender affection turns into gentle melancholy. From a musical perspective, minor is impinging on the tune’s global major key (iv displacing IV). This is a significant point: it is not that major and minor are freely coexisting, but that a primarily major-key tune is pulled in a powerful affective direction by the impingement of a harmonic entity from the parallel minor key. Note that the melody avoids any pitches that suggest either a minor or major orientation—this reinforces the possibility that, in this case, minor is gently tugging on major, rather than there being any conclusive shift from one to the other.

Figure 1. “Ev’ry Time We Say Goodbye,” measures 25–28.

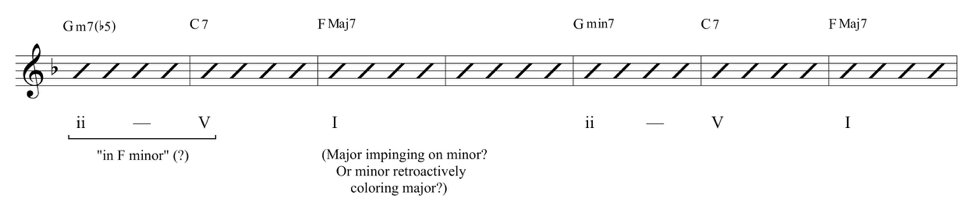

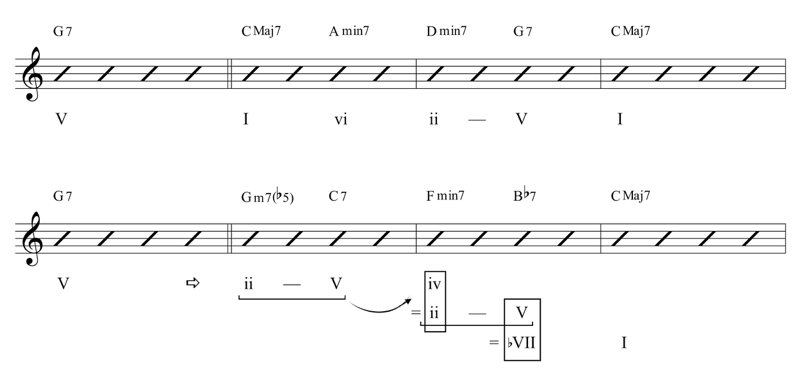

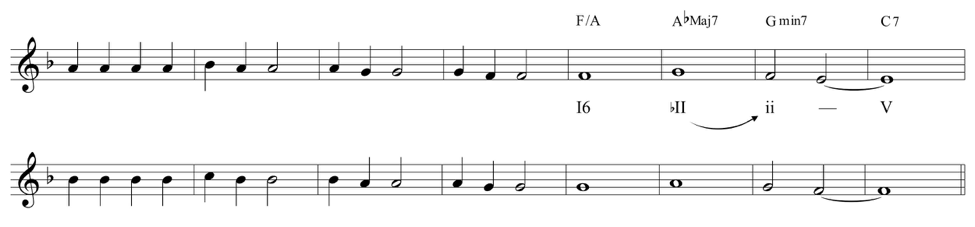

Porter gives us many tunes that effect this major–minor ambiguity in different ways. “I Love You” is one such tune, beginning with a ii–V (Gm7(♭5) to C7) that suggests an F minor resolution, followed immediately by a more conventional Gmin7 to C7. Both ii–Vs resolve to F major, as shown in Figure 2. “I Love You” offers a different take on the relationship between major and minor: by beginning with an evocation of F minor, it seems, briefly, as if major is the one doing the impinging. Or, at the moment of F major’s arrival, we can retroactively recast the opening ii–V as a modally inflected progression that points to F major.

Figure 2. “I Love You,” measures 1–8.

The lyrics are unambiguously celebratory—“‘I love you’ hums the April breeze, ‘I love you’ echoes the hills.” For students who assume that the music always expresses the text (which generally precedes the music, in nineteenth-century art songs for instance), the disjuncture between harmonic mode and textual meaning in “I Love You” reveals ways in which reharmonization might be invoked to stimulate new music-text relations.

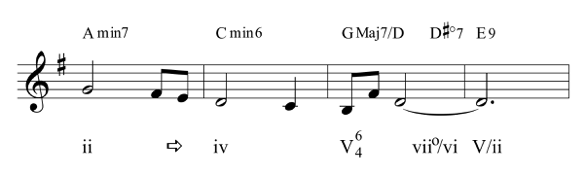

Figure 3 shows the beginning of the last phrase of Johnny Mercer and Johnny Mandel’s “Emily.” Here, a pre-dominant iimin7 chord in the home key of G major is transformed into iv6 (iv with an added sixth), enacting a rising gesture in the bass to V/ii, which returns to ii for the song’s final cadential statement. The move from major to minor pre-dominant harmony is intensified with the change of bass (not least by the way in which the bass rising minor third is echoed in the inner-voice rise from chordal third to chordal third, C to E♭). This substitution reinforces the functional relation between ii (and iiØ7) and IV (and iv).

Figure 3. “Emily,” measures 33–36.

The arrow in this and subsequent examples should be read as “is transformed into.” While these sorts of major–minor oscillations are commonplace in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century concert music, there is a particular use to which this move is put that digresses from earlier practices, and which asks us to think carefully about the nature of harmonic motion and how certain kinds of goal-directed gestures can be imagined.

Approaching tonic—What jazz tells us

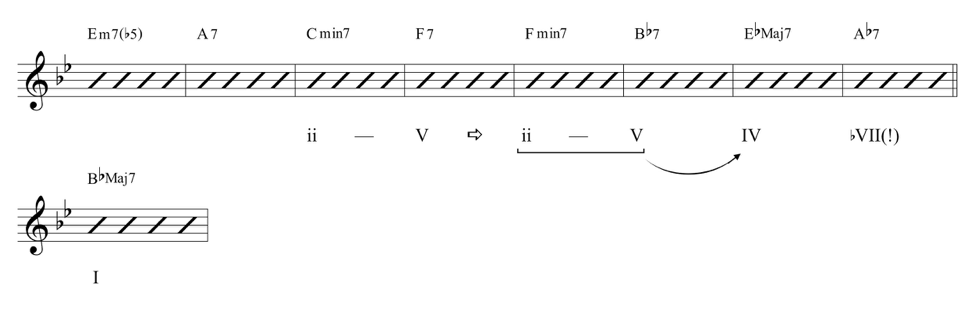

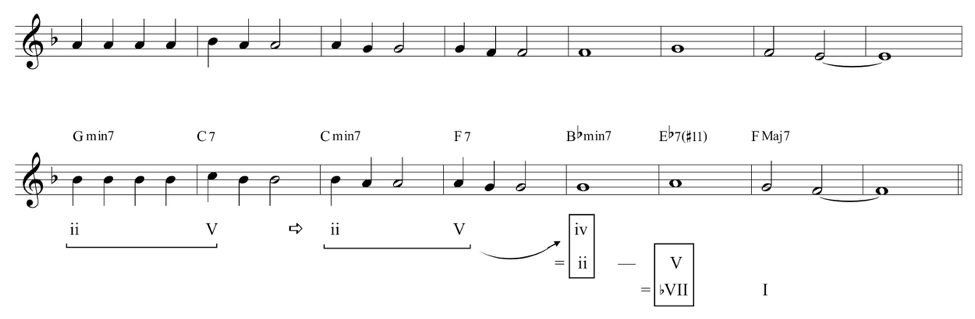

Figure 4 shows the first nine measures of Victor Young and Ned Washington’s “Stella by Starlight,” one of the most frequently played songs in the mainstream jazz repertoire. Its B♭-major tonic is only confirmed in measure 8, and the path it takes to reach that tonic is both elliptical and revealing of an important process in jazz harmony. The V of the ii–V in measures 3–4 transforms via mode mixture to become the ii of a ii–V leading to E♭ major, IV. What began as a trajectory toward tonic (a home key ii–V) is diverted to point toward a subdominant arrival. That IV chord gives way, then, to A♭7: ♭VII, or if one prefers, IV7 of IV, prolonging IV as a temporary goal of motion with its lower fifth. The relation here to a characteristic blues harmonic motion is not insignificant. It is the next move that is most interesting for our purposes, however. The A♭7 chord moves straight to B♭Maj7 as a tonic-affirming cadential gesture! How can this be?

Figure 4. “Stella By Starlight,” measures 1–9.

Figure 5 shows a very similar progression in George and Ira Gershwin’s “But Not For Me.” Here a more conventional move takes us to a subdominant-functioning IV, which is transformed via mode mixture into Bbmin7, which becomes the ii of a locally acting ii–V. Recall that we should be on the lookout (or the hear-out) for ii–Vs, regardless of whether they eventually move on to their implied I, since ii–V is nearly always considered a single syntactic unit with internal voice-leading motion. In this case the ii–V is “in A♭”, ♭III of the home key. But its status as ii–V “in A♭” is secondary in this case to its status in F. Figure 6 extracts this schema, which is fundamental to jazz harmonic practice.

Figure 5. “But Not For Me,” measures 7–11.

Figure 6. Paradigmatic harmonic schema for ♭VII–I motion.

| … IV | ⇨ | iv |

||||

| = ii | ⇨ | V | ||||

| = ♭VII | ⇨ | I |

If this schema is taken as paradigmatic, then it is easy to see that “Stella By Starlight” simply elides the iv chord, moving straight from IV to ♭VII. Or, taken from a different perspective, the mediating ii–V, which we can think of as a single syntactic object with internal voice leading, is substituted by a simple V (see Stover 2015, 172–173).

There are hundreds of songs that invoke this chord progression in exactly this way; it is one of the characteristic harmonic gestures in the repertoire of songs from the American Popular Songbook that serve as the lion’s share of jazz standards. One compelling example, which reinforces several points made thus far, is the last A section of Porter’s “I Love You”—the Gm7(♭5) chord we experienced in measure 1 (see Figure 2 above) is transformed into B♭min7, which becomes the ii of a ii–V moving to E♭, resolving up by whole step to its F major tonic.

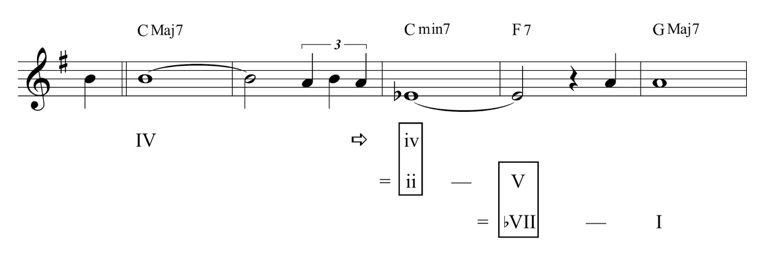

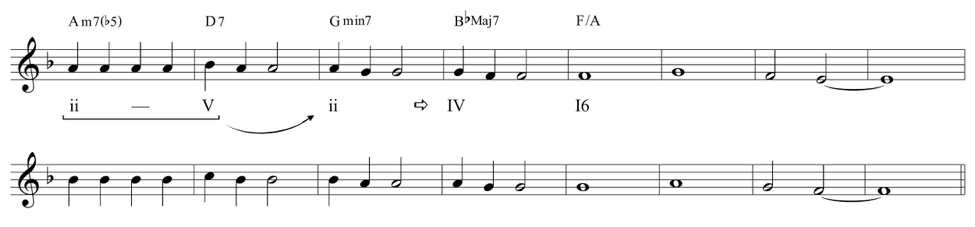

Without understanding how this progression behaves, a student will have a difficult time comprehending, for example, the opening of John Klenner and Sam Lewis’s “Just Friends” (Figure 7). As the song unfolds, it eventually becomes clear that it begins away from its G major tonic, on a pre-dominant CMaj7 chord. This IV chord is transformed into iv (from the parallel minor key), which turns out also to be the ii of a ii–V, which then resolves up by whole step from ♭VII to I. Without knowledge of this common schema, the way in which tonic is achieved in measure 5 would be quite mysterious.

Figure 7. “Just Friends,” measures 1–5.

Recall that ii–V can be thought of as a single syntactic object, and we should not feel a need to select a single harmonic identity for any aspect of it. The Cmin7 chord is both iv and the ii of a ii–V; it is not one or the other, nor is it one and then transformed through temporal experience into the other (although it is transformed through temporal experience from being a minor tonic chord, which is a logical way to hear it, especially the first time around). It is also not important that it is ii–V in any particular key (in this case, in B♭ major or ♭III). We could say it defines a cadential path that moves from pre-dominant to dominant to tonic harmony, with the mediating ii–V occupying a space that subtends both pre-dominant and dominant functional nodes.

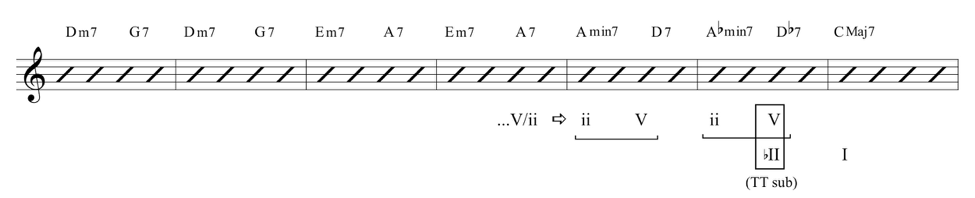

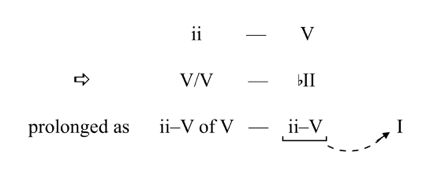

In thinking of the IV ⇨ iv ( = ii–V) to I as a kind of cadential path, we can return to the question of harmonic substitution in jazz. Harmonic substitution, when used sensitively, preserves aspects of the harmonic function of the chord progression being elaborated (see, for example, Garrett Michaelsen’s contribution to this issue). It is highly valuable to understand that many of the basic objects that comprise harmonic substitution are already there in the harmonic language of the songs being elaborated. For example, one of the first substitutions learned by jazz students is the tritone substitution, where a dominant-functioning ♭II7 replaces V7 in the basic progression ii–V–I. Motion by bass descending fifth is replaced by descending semitone. There are many songs where this is found. One particularly colorful example is Duke Ellington’s “Satin Doll,” the first eight bars of which are shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8. “Satin Doll,” measures 1–8.

The pair of ii–Vs in measures 5 to 6 embellish (or are undergirded by) a simple two-measure ii–V leading to tonic, as the notation in Figure 8 illustrates. That is, the Amin7 to D7 of measure V can be interpreted as 1) a transformation of ii to V/V, which is 2) prolonged as a ii–V; again understanding that any ii–V can be read as a single syntactic object. Notice that the Amin7 is reached via modal transformation from the A7 chord (V/ii) that preceded it. Likewise, the A♭min7 to D♭7 can be said to unfold 1) a tritone substitution of ♭II for V, which is 2) prolonged similarly as a ii–V.

Figure 9 expresses all of this as a schematic.

Figure 9. Derivation of the harmony of “Satin Doll,” measures 5–6.

Another way to read this is retroactively: ♭II7 is a local goal toward which the preceding chromatic activity is directed (and ♭II7 eventually points to its own tonic goal of motion, of course). This orientation is useful from an improvisation (or compositional) perspective—the theory instructor should always take care to remind students that reharmonizations are in the service of moving toward some harmonic goal; in this case the tritone substitution for V and its eventual tonic resolution.

Putting it all to use

With this framework of harmonic substitutions in place, what types of classroom activities can help students learn to creatively play within these harmonic possibilities themselves? Before we consider this question directly, we should consider one more example in order to demonstrate a useful technique to engage in the classroom.

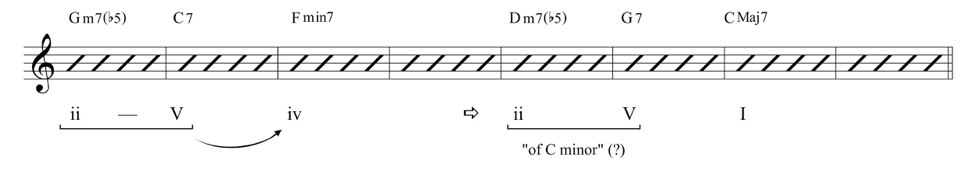

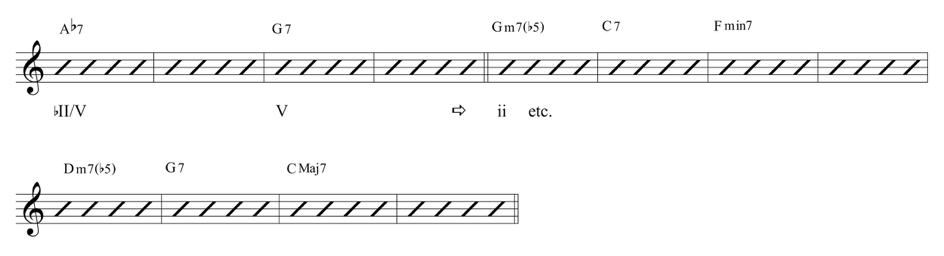

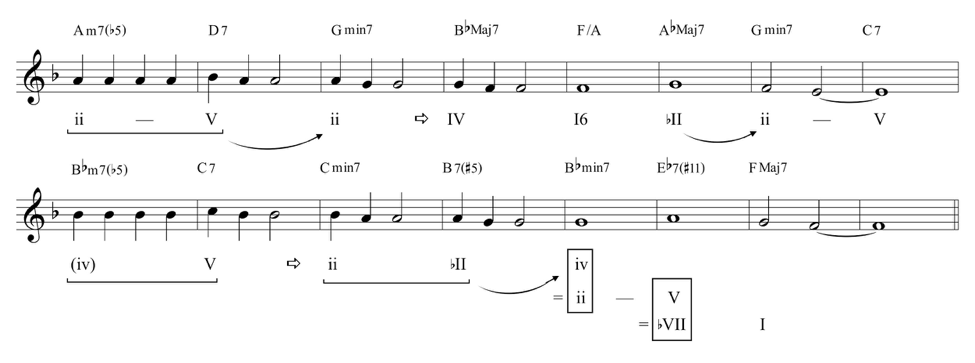

Cole Porter’s “What Is This Thing Called Love?” is another very popular jazz standard, on the short list of tunes every mainstream jazz musician knows. Its harmonic progress, the first eight bars of which are shown in Figure 10, is quite deceptive: an off-tonic beginning, tonicizing iv with its ii–V, the arrival on iv (F minor) is then transformed into a Dm7(♭5) to initiate a ii–V in C minor which resolves, unexpectedly for one hearing the song for the first time, on C major.

Figure 10. “What Is This Thing Called Love,” measures 1–8.

We gain additional perspective on the nature of this elliptical path if we look at the last A section of the AABA tune; particularly if we look at how the bridge leads to the last A section, as shown in Figure 11.

Figure 11. “What Is This Thing Called Love,” measures 21–32.

The bridge ends, like many such tunes, on a dominant chord—itself approached by its ♭II7 (A♭7), the tritone substitution of its dominant—imbued with the expectation of a tonic arrival, at least if removed from the context of having heard the first two A sections. Instead of resolving to tonic, G7 transforms via mode mixture into the half-diminished seventh chord that initiates all of the modally ambiguous motion that we have experienced thus far. The modal shift is mitigated somewhat, by the way, by the melody in the last bar of the bridge, B♭, the ♯9 of the V7 chord.

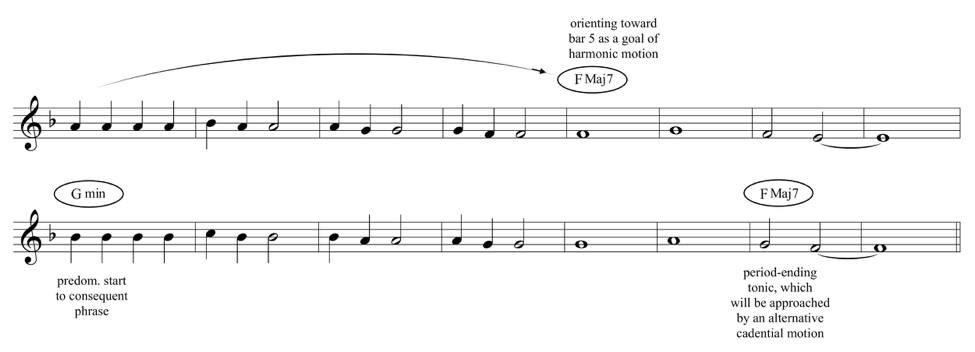

Another way to think of this transformation is to imagine that the expected CMaj7 arrival at the beginning of the A section is delayed considerably—pushed back from the onset to the seventh measure of the phrase. The move from dominant to tonic is prolonged, in this case, by the insertion of a long chromatic passage that only gradually reveals its goal (GØ7 is quite far from C major; Fmin7 less so as iv borrowed from the parallel minor key; DØ7–G7 even less so as a ii–V that does indeed resolve to its goal of motion). This suggests a practical, creative exercise that can be brought to bear in the classroom. The upper system of Figure 12 shows a dominant resolution to a downbeat tonic, the latter of which is prolonged by a I–vi–ii–V–I “turnaround.” The lower system shows a reharmonization of this turnaround that delays the tonic resolution. Instead of a tonic arrival at the beginning of the phrase, the V chord is transformed via mode mixture into the ii of a ii–V of iv, which itself fulfills a dual role as the ii of a ii–V that resolves up by whole step to the expected tonic arrival. Reharmonization, here, not only colors the original chord progression in an interesting way, it also plays with our expectations about tension and resolution by denying the original dominant-to-tonic move and taking the listener along an alternative path toward its delayed resolution two bars later.

Figure 12. Reharmonization of a simple turnaround using mode mixture.

Figure 13 shows the first sixteen bars of Mort Dixon and Ray Henderson’s “Bye Bye, Blackbird.” This harmonically simple tune is an excellent example of a template that can be used for developing some reharmonizations using the techniques outlined in this essay: major–minor mode mixture, alternative dominant-functioning paths to tonic, and tonicizations that prolong various transformed chords.

Figure 13. “Bye Bye Blackbird,” measures 1–15.

The sequence that follows outlines a possible progression of activities that could be done together in the classroom, with students and instructor exploring the various ways that alternative harmonic paths can be created within the context of a tonal chord progression. As a collaborative classroom activity, the students are encouraged to do most of creative work of selecting chords to add or substitute, while the job of the instructor is to raise questions and occasionally encourage students to justify their decisions in their own words.

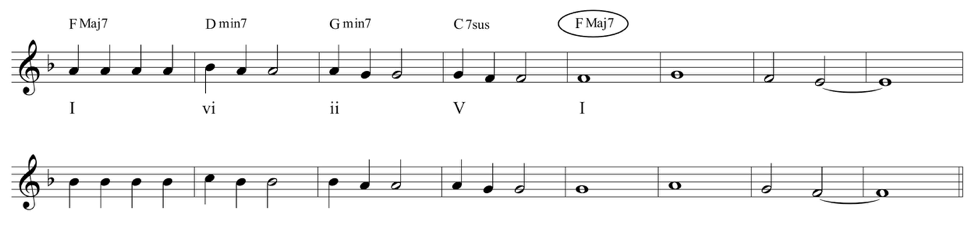

The students’ first step is to quickly analyze the harmony, focusing on goals of motion, tonal areas (such as local ii–Vs), and generally getting a sense of the harmonic landscape of the tune. I’ll refer to these aspects as characteristic gestures below. Their next step, then, is to select a few “anchor” points: harmonies that will serve as important goals (or beginning-points) of harmonic motion. For example, we might select the three anchor points shown in Figure 14, which in turn (1) establish measure 5 as a goal of motion (as a hypermetric downbeat), (2) express the beginning of the second phrase (with its melodic parallelism to the first phrase) as a clear move to a pre-dominant space, and (3) articulate the period’s final cadence.

Figure 14. Three possible “anchor” points around which to imagine reharmonizations.

There are other possibilities that could be explored as well, of course; for example, the Gmin7 chord in measure 13 could be set up as a goal of motion, in a move that parallels the similar establishment in measure 5. Or, conversely, the measure 7–8 half-cadential ii–V could be established as a parallel anchor point to the measure 17 arrival. Indeed, the initial project of choosing different anchor points can suggest many exciting new harmonic possibilities for students to explore.

As Figure 12 above illustrates, one way to maintain a structurally important harmonic space is with a turnaround, the most common by far being I–vi–ii–V–I. Figure 15 shows this: the displaced I chord (the first anchor point) is approached by this common turnaround. Note that the dominant chord is expressed as V7sus to conform to the melody’s scale-degree 1. V7sus is a syntactic chord in jazz; the suspension does not require resolution as it does in some other musical contexts.

Figure 15. Opening tonic prolonged with a I–vi–ii–V–I turnaround.

From here we can prompt the class with a challenge: how can we creatively transform this harmonic progression using various combinations of learned techniques, while retaining the functional identity of the passage? Here is one possible sequence of events, derived from an iteration of this activity that I took a group of students through recently:

-

The vi chord (m. 2) is replaced with V/ii, intensifying the move to ii.

-

This dominant-functioning chord is prolonged with its ii; Am7(♭5) moving to D7. The first chord also functions as a tonic substitute: iii filling in for I. This reinforces the fifth-measure tonic chord as a goal of motion, since it is now the first appearance of a I chord.

-

The V chord, C7sus, is replaced with a pre-dominant BbM7 chord, as a transformation of the Gmin7 (ii) chord that preceded it. We might make a modification like this to reinforce the notion that IV to I can be a tonic-confirming gesture just as effectively as V to I, and to foreground the connectedness between tonal jazz and blues. Of course C7sus would also be highly appropriate chord in this new context, and there are numerous other possibilities as well.

-

Finally, the tonic arrival in measure 5 is recast as a first-inversion chord (see just below). The modified chord progression is shown in Figure 16.

Figure 16. Four modifications to the opening turnaround.

The rationale for a first-inversion tonic chord in measure 5 has to do with what happens next. The half-cadence arrival at the end of the first eight-measure phrase (followed by a restart on pre-dominant harmony to begin the parallel phrase) is an important characteristic gesture—a non-resolving half-cadential ii–V—that we might consider leaving intact (as another anchor point?). Between the first-inversion tonic and the half-cadential ii chord an A♭M7 has been inserted, ♭II of ii or a tritone substitution of V of ii, resulting (1) in a descending chromatic bass A–A♭–G, and (2) in a second way to approach ii that is functionally related to the first (the D7 to Gm of measures 2–3) but that varies the “color” of the approaching chord. All of this is shown in Figure 17.

Figure 17. Approaching the phrase-ending half cadence.

The V chord that ends the first phrase does not need to resolve—it points back harmonically to what has transpired thus far, much like an interruption in earlier tonal practice. The second phrase, in the original song, begins on pre-dominant harmony. This, then, is another characteristic harmonic gesture that gives “Bye Bye Blackbird” its identity, which as a class we might consider keeping intact (a point that I often need to gently underscore while considering other possibilities put forth by students, while not dismissing those possibilities). The second phrase also ends, importantly, on tonic, and I have already suggested that we approach that tonic with the alternative cadential motion that has been one of main thrusts of this essay. Figure 18 shows one solution that keeps both of these desires in mind. The new progression in Figure 18 was construed in roughly the following order:

-

The ii–V B♭m7 to E♭7 is inserted as an alternative phrase-ending cadence.

-

The B♭m7 chord, iv, is approached with its ii–V.

-

A V chord is inserted in the second measure of the phrase, prolonging the initial ii into a ii–V, which is then transformed via mode mixture into the next ii that eventually points to B♭ minor.

Figure 18. Reharmonizations in the second phrase.

Finally, given the full context of a reharmonized period, we might make a couple of small aesthetic modifications. In the first phrase, the descending bass A–A♭–G is a salient gesture that contributes to harmonic identity of the new, reharmonized version of “Bye Bye Blackbird.” It might be valuable to repeat that kind of a gesture in order to reinforce its significance. This can now be seen in measure 12, where the V7 of iv is replaced with ♭II7 of iv, resulting in the chromatic bass descent C–C♭–B♭. And finally, because we have already encountered two Gm7 chords as structurally important pre-dominants, another pre-dominant chord is invoked to begin the phrase, B♭m7(♭5). We might make this particular choice both because there is already a B♭m7 four bars later (and perhaps don’t want to “give away” that sound yet) and to reinforce that harmonic substitution with mode mixture is a valid and pervasive practice—this is why we have not used, say, B♭ major chord as the substituting chord, although that would also work very well too.

Figure 19 shows the entire reharmonization.

Figure 19. “Bye Bye Blackbird,” complete reharmonization of measures 1–15.

This is, of course, one of many solutions. What is important here is thinking about the developmental process that drives various selections:

-

Finding anchor harmonies: characteristic harmonic gestures that can act as salient goals of motion (but which can themselves also be modified, as long as their functional identity remains intact; viz. the B♭m7(♭5) of measure 9),

-

Thinking creatively about paths that we might follow that lead to those points, with a focus on particular paths we have explored thus far (in this essay: mode mixture, prolonging either ii or V as ii–V, and functional substitutes for dominant chords),

-

Returning and revising in light of new local or longer-range contexts as they emerge.

Every step along the way the class should sing together—I like to divide the class in two with some singing the melody and some singing the bass (in whole notes, in this case), perhaps with piano accompaniment as well. An advanced version would be to sing guide tones connecting inner-voice chord tones, but that is a project for another paper. Singing the bass line in Figure 19 reveals two important features: (1) a protracted build-up toward the first root-position tonic arrival in measure 17, and (2) the degree to which the alternative final cadence satisfies the resolution-drive toward that tonic.

While the kitchen sink has been thrown into this reharmonization (while still remaining within the confines of the techniques discussed in this essay, and paying close attention to harmonic function), the interested instructor or student can also begin to think about smaller, less radical ways of altering chords to express different modal identities. Find places where a iiØ7 can be substituted for a iimin7. Seek out ways to tonicize a structurally important harmony with its ii–V. Displace a temporally extended chord (like the five-bar-long FMaj7 that begins “Bye Bye Blackbird”). Recast a cadential gesture by moving from ♭VII, ♭II, or III to I. Reharmonization is a key tool employed by most every improvising jazz musician. It is also an extremely valuable tool for composers (extending one’s vocabulary of harmonic devices that can fulfill a given expressive need) and performers (thinking about how to interpret a given harmonic context—how to bring out features of harmonic motion through performance). This brief essay demonstrates some ways to think about reharmonization while preserving the harmonic identity and the overall goal-directed motion of a tune, while at the same time expanding on the notion of what those two concepts can mean.

This work is copyright ⓒ2016 Chris Stover and licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution–ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.