Engaging Students: Essays in Music Pedagogy, vol. 4, Engaging Students Through Jazz

Coalescing Learning around a Coltrane Classic

Shersten Johnson, University of St. Thomas

Teachers of music theory courses tend to have favorite pieces that they return to again and again for a variety of reasons. Sometimes we choose those key canonic pieces that we believe all students should encounter at some point in their training, and sometimes we choose a piece because it crystallizes a number of teaching points in explicit, sequenced, and even importantly problematized terms. One of my favorites in this latter category is Mongo Santamaria’s “Afro Blue” (1959) adapted by John Coltrane (1963) (Live at Birdland recording and The Real Book lead sheet.)

Coltrane’s “Afro Blue,” like his more well-known adaptation of “My Favorite Things” (1961), features Coltrane on soprano saxophone (an instrument that he championed) in a fast jazz waltz. The piece exploits a limited vocabulary of adjacent chords used in parallel fashion without typical tonal resolutions. Neil Tesser describes this horizontally focused musical language in his Grammy-winning notes to the re-mastered album Afro Blue Impressions by saying that Coltrane turned 90 degrees from the vertical structures of the 1950s to a “new method of improvisation, one that eschewed harmonic movement almost entirely to better facilitate an expansive lyricism.”

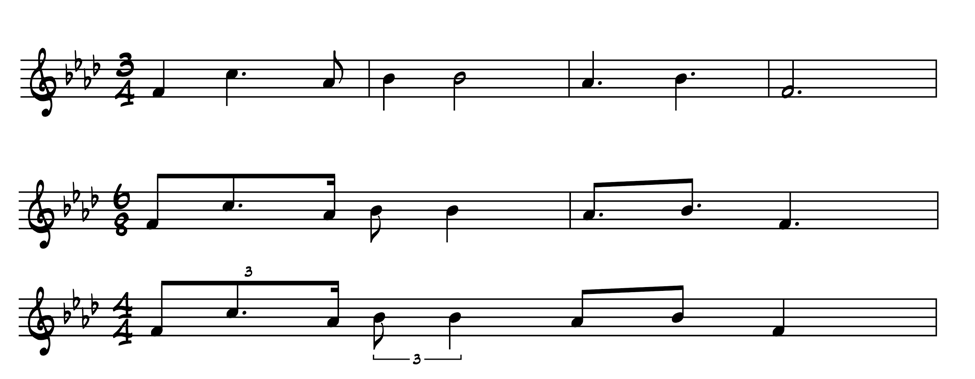

The head of the tune—four four-bar phrases in the form a a’ b b’ notated in Figure 1—leads to a brief solo followed by the return of the head and then an ornamented repetition. Lengthy piano and saxophone solos comprise the middle of the piece, and then the main tune returns at the end with a slow-motion climax with augmented rhythmic values. The tune itself begins with the bold solo entry of Coltrane’s reedy soprano, grabbing listeners right away with his signature staccato phrasing. The first bar’s lilting dotted rhythm opens up pitch space by ascending from scale degree one up to five and, with the second measure’s bouncy quarter–half (as performed), signals a light-hearted dance. The rest of the quartet enters in the polymetric third measure, pitting duples against triples, and the phrase settles back down to tonic at its end. The “b” phrase features pitches that circle around but avoid tonic and it finishes with a deliberate ascent from from submediant to tonic. Thus, with its mixture of a simple, memorable melodic idea (heard three times in the first minute of the piece), compelling cross-rhythms, and modal treatment of repetitive harmonies enveloped in a complex, improvisatory texture, this piece offers a number of ready entry points for student investigations while also affording several obstacles to be negotiated. It provides an ideal piece to engage students deeply.

Figure 1. Head of “Afro Blue” (adapted from a popular simplified lead sheet easily accessed online).

While I have used the Live at Birdland recording of “Afro Blue” successfully in the classroom, I also draw on the Jazz Casual production produced by Ralph Gleason (1963). The Birdland recording is brighter and edgier with a wash of cymbals and a dizzying saxophone entry that soars in after a lengthy piano solo at about 4:50. It is also longer (at almost 11 minutes), played at a slightly faster tempo, and the tune is more ornamented, which may not work as well in the classroom. The Jazz Casual version, in addition to being a little simpler (omitting the leap to A♭ in the penultimate measure of the head, for example) has the added advantage of video which, if time permits, can facilitate a more nuanced discussion of style. Both recordings feature John Coltrane on soprano saxophone along with McCoy Tyner (piano), Jimmy Garrison (bass), and Elvin Jones (drums).

Although “Afro Blue” could be explored productively at various stages in music theory courses, I will argue in this essay that this tune is a great one to use early in the sequence because it provides a nexus of examples of recently introduced concepts (simple and compound meter, borrowed beat divisions, modes, and triads) at a slightly more difficult level than students will have encountered previously. These concepts will benefit from reinforcement through careful guided listening, and examining the lead-sheet notation after a thorough hearing can facilitate a smooth transition from the topic of triad construction to that of seventh chords, affording the opportunity to expand the vocabulary of chord symbol notation. For this reason, I start with the simplified lead sheet and reserve the “official” version for a later lesson on extended chord substitutions.

Engagement of the tune at this point early in the sequence will not only allow deep practice of concepts from earlier in the semester and the explication of the learning objectives of the seventh-chord lesson but also the introduction of (or increased familiarity with) musicianship tools that will be used consistently from that point on. In addition, Coltrane’s modal horizontal style prepares a foundation for talking about linearity in upcoming units on counterpoint and voice-leading. Finally, I will demonstrate that this piece can be used to offer students a variety of enriched experiences (transcription, lead-sheet analysis, improvisation) beyond the typical music-theory textbook example or workbook exercise.

In the following paragraphs, I will walk through the activities and learning objectives I have in mind in more detail: increased familiarity with modal construction, review of metrical accent displacements, melodic transcription practice, expanded lead-sheet analysis, musicianship skills practice (solfège, arpeggiation, conducting, performing rhythms, improvisation), and introduction to seventh-chord construction. Furthermore, I will attempt to link this nexus of teaching points to others in the network of previous and future lessons. Ultimately, I will show that, while obviously not the only vehicle for exploring these topics, “Afro Blue” condenses a variety of important concepts in one place while affording a welcome break from more routine exercises, allowing students to sink deeply into music in a fascinating idiom (that may or may not be familiar to them) in a logically sequenced way.

Listening and melodic transcription

During the initial listening of the first few minutes of the tune, students can write their reflections, listing anything they notice. Listeners will benefit from a reminder about features on which to focus: style, performers (if known), instrumentation, meter, mode, and form. They can also make a list of what features are familiar or unfamiliar. Students may be less acquainted with certain style characteristics of “Afro Blue,” and a short written reflection while listening can help those who work at different paces absorb the details of the piece.

Transcribing the melody into notation requires deciding on a few parameters, the first of which is meter. Because students tend to hear beats at different levels of metrical hierarchy, performing the deep slower pulses and the faster shallow pulses with different parts of their bodies as they listen to the complete texture can help them draw conclusions about beats and beat divisions. This step is particularly helpful before starting a transcription of the melody, which can confuse students with its polyrhythmic play. Some will hear the fast simple-triple meter that characterizes this jazz waltz and choose a 3/4 or less likely a 3/8 time signature. Others will hear the fast three as compound divisions in a 6/8 meter. Still others may hear a simple duple or quadruple meter with occasional triplets. Students may either compare the options and come to a consensus on a single time signature or notate the melody in the meter of choice and compare their versions later. The tune is short enough that it can be notated on the board in several versions, one above the other, in different meters (3/4, 6/8, 4/4) for comparison, something like those shown in Figure 2. Conducting along can clarify the meter further, and students will usually come to a consensus that 3/4 meter “feels” right.

Figure 2. Three possible transcriptions of the first phrase of “Afro Blue.”

Having heard the head of the tune several times, students can sing it together on a neutral syllable and conduct along, counting measures. They can then attend to other features of the tune. They will discover that the tune divides into phrases and will be able to point to some elements that help them hear closure, such as the return to scale degree one and longer note values. The fact that students haven’t officially studied phrase models by this early stage is not a problem, since these phrases don’t follow the traditional models. They can then map out the measures on their staff paper and sketch in rhythms above the staff.

When adding in the pitches, students sing what they think the tonic is and make observations as to why they have chosen that note. (It’s the first note of the first phrase and last note of each phrase, for example). A classmate or two may know exactly what pitch class acts as tonic, but if not, the note can be provided or they can find it from a C played on the piano. Then they can sing a scale from that tonic and determine the mode.

Transcribing the melody can be difficult due to the beginning solo entry, quick initial leap, and dotted figure, which make this piece a good model for students finding places other than the beginning from which to start. Listeners will discover the sort of “rhyme scheme” created by phrases that all end on what must be the tonic (based on sheer repetition and melodic focus despite the lack of leading tone) and will be able to work backwards from there if need be. Forcing attention to another part of the phrase is an important skill in transcription, and this tune fosters it gently by coming back to tonic so frequently.

Comparing notes

Once transcriptions are complete, the tune can be written on the board, and “comparing notes” between students’ solutions will serve to illustrate several points. Singing an agreed upon version using different forms of solfège—do-based and la-based—will highlight the modal nature of the tune and spark a review of the Aeolian mode as well as modality vs. tonality in general. This activity builds on a previous assignment in which students compare the Dorian-mode “Greensleeves” with its minor cousin “What Child Is This?” to isolate modal scale degrees and leading-tone alterations.

In a further discussion of the meter, students find that what would normally be thought of as beats (quarter notes in a 3/4 time signature) feels like compound divisions of a beat at this tempo. With that in mind, they can turn to a description of the rhythmic figure that occurs in the third bar of each four-bar phrase. Though notated as two dotted quarters in the lead sheet, the figure is played slightly differently in the four phrases and versions, so generalizing from the articulation points will be necessary. They go through the terms they learned when studying displacements of typical metrical/rhythmic accents, asking how this figure compares to the definitions. They agree that the figure creates an off-beat accented syncopation on the “and” of the second beat, which divides the measure in half into two duplets and which further creates a polyrhythm against the drums’ three-part division of the bar. Some classmates may suggest that the figure is also an example of a hemiola because it has two notes in the space of three. That definition can then be compared with the more typical “dictionary example” of the Baroque hemiola: three groupings of two in the space of two groupings of three. Conducting along with the head in simple two-part divisions of the bar will spark some observations about the way these duplets are performed vs. the way typical simple divisions are performed.

Finally, the fast jazz waltz style can be explored further by comparing it with other jazz waltzes like Coltrane’s “My Favorite Things” or Guaraldi’s “Skating” from A Charlie Brown Christmas. Investigating “Skating” can lead to a discussion of the four-bar hypermeter, which is foregrounded much more strongly than in “Afro Blue.”

Lead-sheet analysis

When introducing lead-sheet notation, students can compare this conceptual model of musical shorthand with other forms of condensed notation. They review the features of the lead-sheet: a one-page summary of the head of the tune with chord symbols and brief suggestions for solos. The instructor can define any unfamiliar terms like “minor blues” and provide background information on the composer, Santamaria. Playing the Santamaria version for comparison will present listeners with the opportunity to point out where that version differs from the lead-sheet notation. Exploring the lead sheet in its entirety and larger context helps student musicians understand what kinds of musical features are typically included.

Some students will likely be able to ascertain the meaning of the minus sign used in the chord symbol notation on the lead sheet (e.g. F–7). This is a good point to explain how seventh chords are constructed if they haven’t been talked about yet. A discussion of seventh chords built on each scale degree in the Aeolian mode will draw attention to the Gm7 chord used in the tune and students will discover that it requires a note outside of the F Aeolian mode (D♮). Further exploration can tease out why that chord is chosen by singing the progression as arpeggios, first with the Gm7 and then with its half-diminished correlate. Analyzing the chords and their ascending and descending stepwise motion leads well to a comparison of pieces in other styles that harmonize stepwise bass lines, for example Clapton’s “Change the World” (E–F♯m7–G6–F♯m7–E) and Mozart’s K.331, mvt. 1 (A–E7/G♯–F♯m–E7/G♯–A). Classmates will be able to think of other examples as well. Contextualizing Coltrane’s piece in this way ties to future lessons in which learners work with passing motion and eventually planing.

Having noticed that the tune is modal and is without a leading tone, students can speculate as to how the chords help them hear the final Fm7 chord as having a sense of closure. Learners can explore what harmonies do the work of the dominant chord in this tune, particularly focusing on the emphasis of the E♭ harmony at the beginning of the third phrase. They can point to the series: D♭–E♭–Fm7 proceeding in a stepwise fashion which, through sheer repetition, affords the last chord a sense of finality. They can also point to the E♭ and G in the melody that circle around but avoid F in the last part of the tune, carving out a target area in pitch space that must finally be filled by the F. This activity reinforces notions of pitch centricity vs. tonal centricity as well as highlighting style markers of minor blues.

Improvisation

Taking another listening pass while following the lead sheet sets the stage for a discussion of improvisation. Students can then categorize the alterations in the tune that they hear, for example:

- dotted-half notes replaced with smaller note values like quarter-plus-half

- a two-note tag on the end of the head and a lead-in to the repetition

- grace notes added to the last phrase

Students brainstorm other places to use these same types of embellishments and sing the tune with these while employing more repetitions as needed.

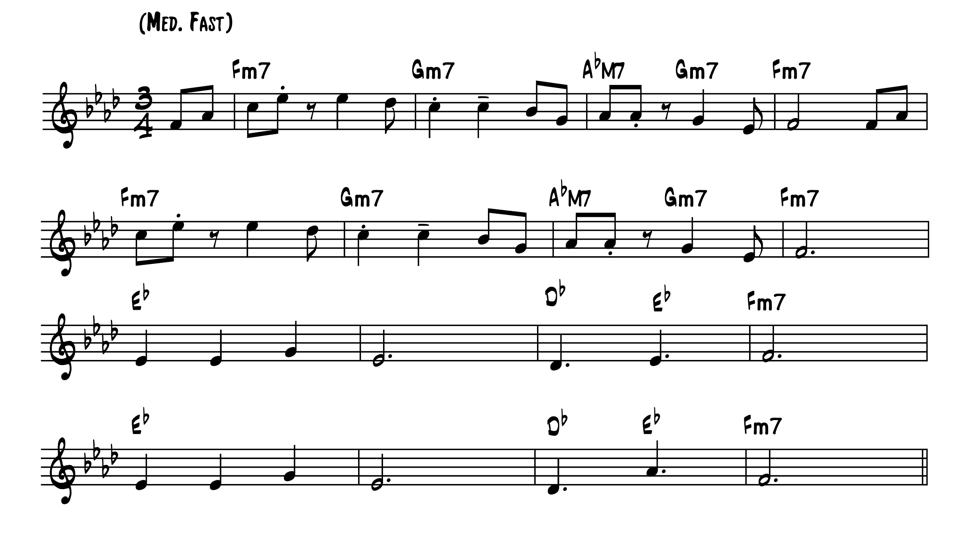

The lead sheet’s written-out embellishments on the repetition of the head, notated in Figure 3, provide further explorations. Learners note, with a bit of guidance, the opening arpeggiation of the Fm7 chord, which facilitates the expansion of what had been a fairly restricted melodic ambitus into a longer descent. The question may also arise as to why only the first half of the head is embellished and it can be tested by using those rhythms and melodic figurations to suggest alterations for the second half. If time permits, the discussion can expand to other recordings like the Live in Stockholm version (1963) to survey other improvisational embellishments. Studying the end of the piece where there’s less evidence of the tune and more improvisation leads to a discussion of where the tipping point lies between variation and contrast. Doing this work—identifying an artist’s improvisations and applying them in new situations—can also prepare for later discussions of the alterations used in motivic development and theme variations. Ultimately though, it helps young musicians start to think about how they might improvise using the simple building blocks like those observed.

Figure 3. Embellished head of “Afro Blue” (adapted from the simplified lead sheet).

Conclusion

“Afro Blue” is a unique tune that has much to offer beginning music theory students. Its concepts can be logically woven in with examples from other genres, and can also be used to introduce new methodologies of listening and improvising. Engaging a modal melody such as this one paves the way for the study of modal music of other popular styles that many musicians wish to explore but that are not central to traditional theory texts. This tune can also afford a jumping‐off point for a later demonstration of improvising variations on a melody, or re-composing using chord substitutions, and can lay the groundwork for later discussions of guide tones and alternative styles of voice-leading. Most important, students will be able to practice performing in solfège, arpeggiating chords, conducting, tapping rhythms, and improvising melodic embellishments, all while studying a historically significant classic with a captivating tune that will leave them humming for the rest of the day.

This work is copyright ⓒ2016 Shersten Johnson and licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution–ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.