Engaging Students: Essays in Music Pedagogy, vol. 3

Inverting Analysis

Daniel B. Stevens, University of Delaware

Introduction

The mind, it’s been said, is not capable of fully understanding the answer to a question that it has not yet asked. Jumping right into a score-based or aural analysis of a full piece is, for most students, like reading the answers before they have been able to formulate a single probing question. They might get the labels right without appreciating their musical significance ― i.e., the questions they answer.

Inverting analysis provides an effective solution to this pedagogical problem by placing score and aural analysis at the end of the analytical process rather than the beginning. The basic principle is simple: any analytical insight that students might be expected to gain through conventional analysis (chord symbols, linear and dissonance analysis, etc.) should first be explored in a simpler form using quick, focused improvisations or compositions. The technique: propose and explore the compositional question first, developing a sense of the musical possibilities inherent in the given material, then study the way a specific piece engages those possibilities.

This is not the first essay to propose using (re)composition and improvisation to engage students in meaningful analysis. BaileyShea, Hoag, Johnson, and Schubert offer useful and insightful applications of this analytical method. In another publication, Schubert’s adaptation of Mozart’s “see what an ass I am” approach, demonstrated in a series of YouTube videos (1, 2, 3, and 4), beautifully captures the interplay of improvisation and analysis that inverting analysis seeks to establish. As Schubert notes, it is always pedagogically advisable to present students with music that is within their analytical and aural grasp. This principle also applies to inverting analysis: any musical feature too complicated to emulate and conceptualize through composition and improvisation is probably beyond students’ ability to comprehend in a meaningful way using conventional analytical tools. Keeping the musical problems simple also helps minimize the time between the start of an inverted analysis and the “payoff,” when the piece itself is finally revealed and analyzed.

Unlike the articles mentioned above, which describe the use of inverting analysis at advanced and graduate levels, this essay focuses on applying this technique in first-year harmony courses. Each of the examples below has led my students to experience distinct “aha” (or sometimes, “this is more complex than I first realized”) moments, despite the relative simplicity of the musical materials being considered. While almost any musical feature could be the starting point for an inverted analysis, I will provide examples in which the teacher supplies the bass line or the melody from an existing piece of music.

Inverting Analysis Using a Given Bass

For most pieces, closely considering the formal, harmonic, and contrapuntal implications of the bass is a valuable starting point for analysis. By isolating the bass line, students learn the powerful role this line plays in shaping the phrase.

Approach No. 1: Chordal Analysis

One of my favorite games in class is to challenge the students to infer a complete roman numeral and figured bass (RNFB) analysis of a phrase based on its bass alone, and then to discover how closely their “guesses” correspond to the composition. It is common for students’ inferences to be 70–90% accurate.

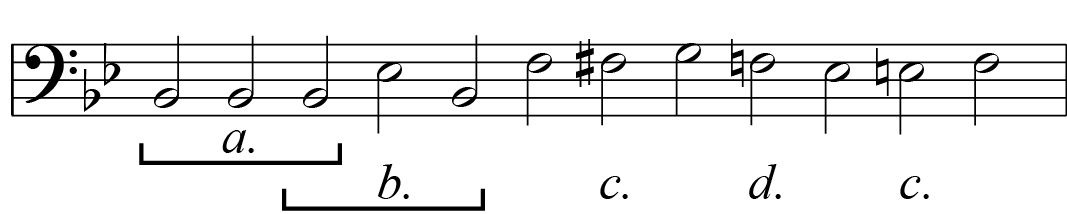

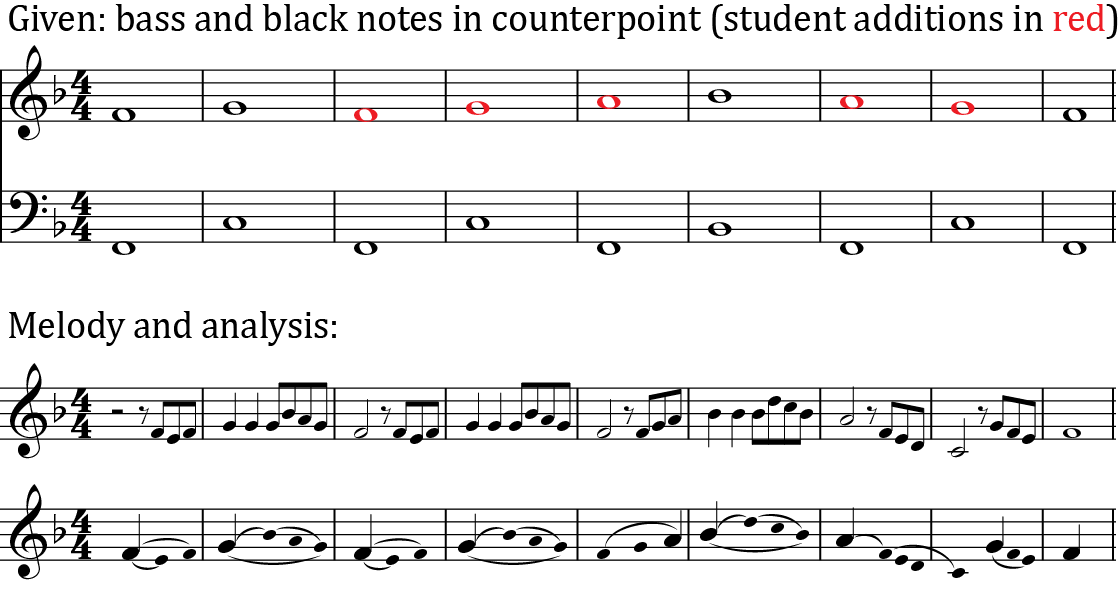

Consider the bass line provided (without rhythm) in Fig. 1, taken from the first phrase of St. Anthony Chorale from the Divertimento in B-flat major (a theme attributed to Haydn and made famous by Brahms’s Op. 56 Variations). Rather than starting an analysis of this piece by displaying the score, which may overwhelm students, an inverted approach begins by writing these notes on the board, saying “this is the bass line of the first phrase of a composition that we are studying today. What can we figure out about this phrase based on this line alone?” (Let’s assume that the students are already comfortable with phrase functions, RNFB analysis, species counterpoint, and an introduction to secondary functions.)

Figure 1. Haydn (attr.), St. Anthony Chorale (from Divertimento in B-flat major), mm. 1–5, bass line.

Students might initially observe that the phrase ends on a half cadence, begins with two tonic-expanding bass lines (marked “a” and “b”), has two chromatic tones (“c”), and a dominant tone (“d”) that would not likely be harmonized as V, given the unstylistic syntax this would suggest (vi–V–IV). Going deeper, students might recall that a tonic expanding pedal bass (do–do–do) could be harmonized with a neighbor IV6/4 or a common-tone diminished-seventh chord. The instructor could play both versions and ask the students to make an educated guess, based on context and musical experience, about the identity of the second chord. Students might explore the possible harmonizations of the F-natural at “d”: expanding a predominant or simply functioning as a passing tone connecting vi and the predominant chord on E-flat. They could also bracket the chromatic tones as passing or consider their possible functions as secondary dominant chords. Finally, students could quickly sketch the voice leading for their inferred progression in four parts, fully realizing its contrapuntal implications.

Of course, to infer all of the above is only to scratch the surface of this interesting phrase. To bring the students into more meaningful contact with its unique interplay of harmonic stasis, harmonic movement, and phrase length, teachers could create an in-class problem-based learning activity, posing three open-ended questions: (1) where do the harmonies invite rhythmic stasis (longer values) and acceleration (shorter), (2) what meters, harmonic rhythms, and phrase lengths might set this bass (and the progression it implies) in a satisfying manner, and (3) what might the basic structure of this chorale-style melody be (starting pitch, movement around evaded cadence, cadential figuration)? These questions will lead students to engage issues such as whether the evaded cadence creates a phrase expansion, which of the first five chords will receive agogic emphasis, and where predominant and dominant harmonies are placed within the phrase. Students who engage these compositional questions typically approach the first phrase of the St. Anthony Chorale with a palpable sense of awe and respect, attending to every detail.

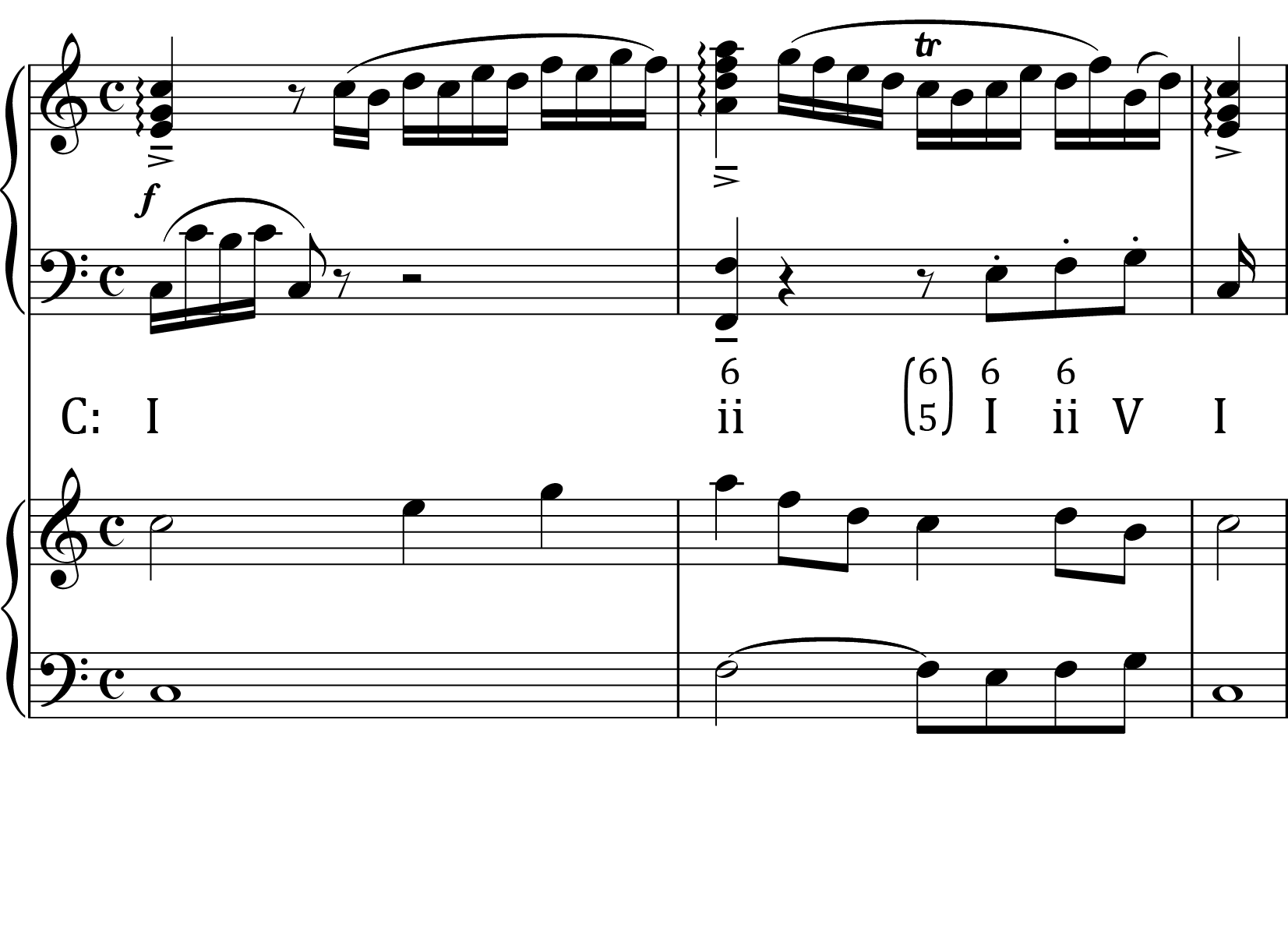

Inverted analysis also draws students’ attention to those chords whose function differs from the possibilities inferred from the bass. For instance, the bass line of the opening of Mozart’s Piano Sonata in C Major, K. 279, given in Fig. 2, seems to imply a straightforward tonic expansion (“a”) followed by predominant (“b”) and cadence (“c”). Accordingly, most students correctly infer the opening tonic, the predominant (students typically guess ii6 or ii6/5), and cadential chords.

Figure 2. Mozart, Piano Sonata in C major, K. 279, mm. 1–3, bass line.

However, Mozart’s harmonization of the tonic expanding bass (“a”) is surprising. Students who have learned common tonic-expanding idioms will expect that the opening tonic is expanded with either a V4/2, a viiØ4/3, or IV, options that instructors can demonstrate at the piano. Yet, Mozart apparently eschews all three options by harmonizing the second bass note as a ii6, as reflected in the student analysis and reduction in Fig. 3.

Figure 3. Mozart, Piano Sonata in C major, K. 279, mm. 1–3, student analysis and reduction.

Despite the unusual syntax of this harmonic analysis and the problems it creates for linear reduction (e.g., many students are tempted to read the C5 as a chordal seventh of the supertonic, though this dissonance does not receive clear downward resolution), students who approach the score without thinking through the harmonic possibilities of its bass are unlikely to consider alternative analyses. In contrast, those who take an inverted approach will consider this passage not in a vacuum but in relation to the harmonic idioms suggested by the bass. Such students usually discover an alternative harmonic and linear reduction, in which the ii6 in m. 2 becomes a viiØ4/3 through the arpeggiation in the right hand (see Fig. 4), leading to a second surprise (“the idiom I expected is there after all!”).

Figure 4. Mozart, Piano Sonata in C major, K. 279, mm. 1–3, alternative student analysis and reduction.

Like many pieces of tonal music, this passage seems simple on the surface, but a closer look reveals a complex interaction between bass, harmony, and melody. Focusing attention first on its bass and exploring possible harmonizations enables students to critically compare alternative harmonic and contrapuntal interpretations. Further, students gain understanding of the role expectations play in analysis, including their power to highlight significant features that might otherwise have escaped attention.

Approach No. 2: Contrapuntal Analysis

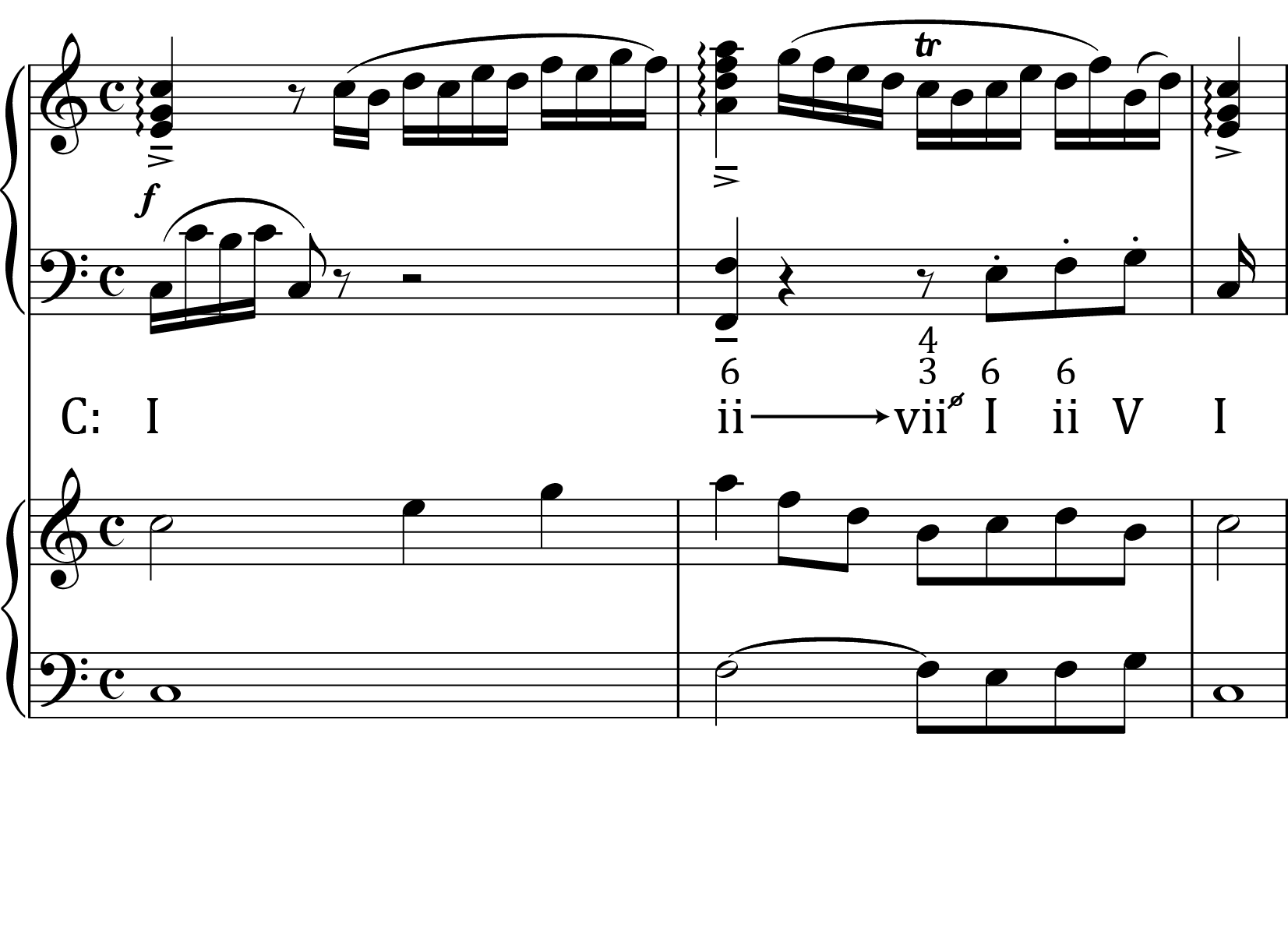

Exploring possible contrapuntal relationships above a given bass provides students another useful starting point, and is especially good for quick and spontaneous aural analyses in class. One inverted approach involves extending the guide-tone method (a technique used for harmonic dictation and developing active listening) to infer possible contrapuntal relationships above a bass. In this approach, students first consider whether do or ti is consonant (or workably dissonant) above each note of a given bass. In cases where both do and ti are possible, students weigh each option based on harmonic and contrapuntal context, general listening experience, and their individual aesthetic sensibilities. (NB: as a heuristic construct, the guide-tone line is not identical to an upper voice; thus, a strict guide tone line may create parallel octaves when the bass itself moves between do and ti, such as in the pre-chorus below.)

Fig. 5 provides the bass line of “I Will Wait” by Mumford and Sons and a typical provisional guide-tone line.

Figure 5. Mumford and Sons, “I Will Wait,” bass and guide-tone lines.

After using context to identify do (and the non-tonic opening), students focus on choosing guide tones for notes “a,” “b,” “c,” and “d.” The notes at “b” and “d” could each be set with either do or ti; note “c” would likely be set with do to avoid voice leading problems from “b” to “c.” This process is best approached by asking the students (as a class or in small groups) to improvise possible guide-tone lines above the bass. Having engaged the contrapuntal implications of the bass aurally, students are quick to pick up on one of the song’s most striking features: the presence of do throughout the chords marked “a” ― the very chords they expect most strongly to move to ti. Students also better appreciate how chord “d,” harmonized as mediant instead of tonic, breaks expectation.

First species principles are (loosely) applied in another inverted approach, which I call “walking the (contrapuntal) line.” Above the given bass, instructors provide the first, last, and peak notes of a species-style reduction, and students fill in the gaps. The resulting contrapuntal framework provides a starting point for studying melodic structure and diminutions (see Fig. 6). A third inverted approach engages pieces whose first chords deviate from the normal 5/3 contrapuntal structure. In short, asking students to improvise counterpoint above a given bass helps them listen horizontally and perceive the linear relationships found in different musical styles.

Figure 6. Johnny Cash, “Walk the Line,” verse and refrain, reduction and melodic analysis.

Inverting Analysis Using a Given Melody

Using melodies as the starting point for an inverted analysis leads to more open-ended compositional questions than using the bass. While this approach may require more class time, the opportunity for students to consider the harmonic, contrapuntal, structural, rhythmic, and stylistic qualities and implications of melodic lines is invaluable. The goal remains to explore the compositional issues involved in setting a particular line, rather than to find the “right answer,” so that the analysis occurring at the end of the inverted process is meaningful and revelatory.

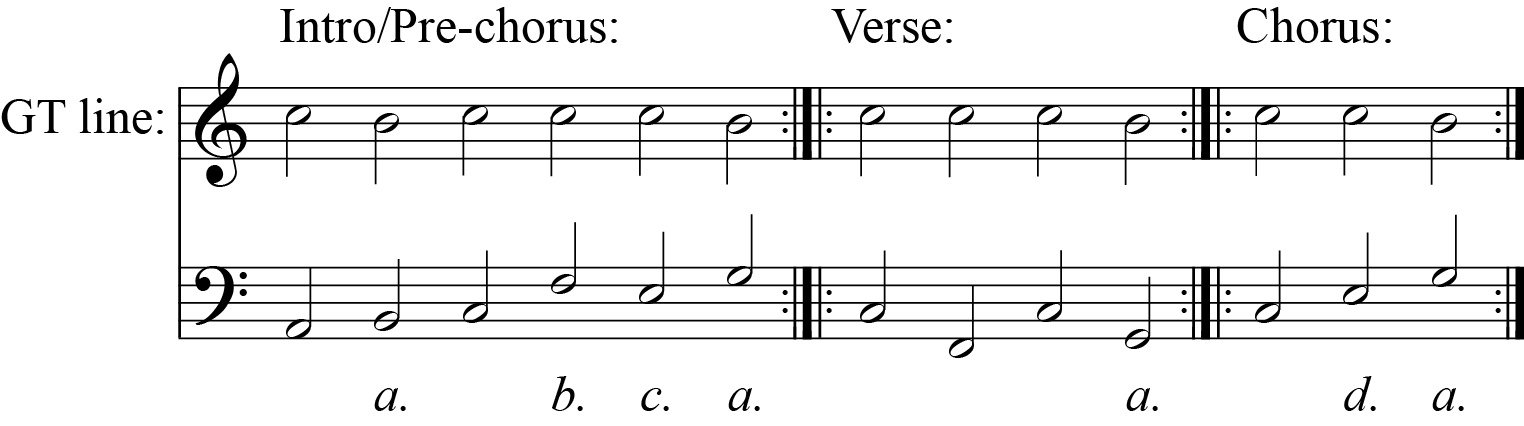

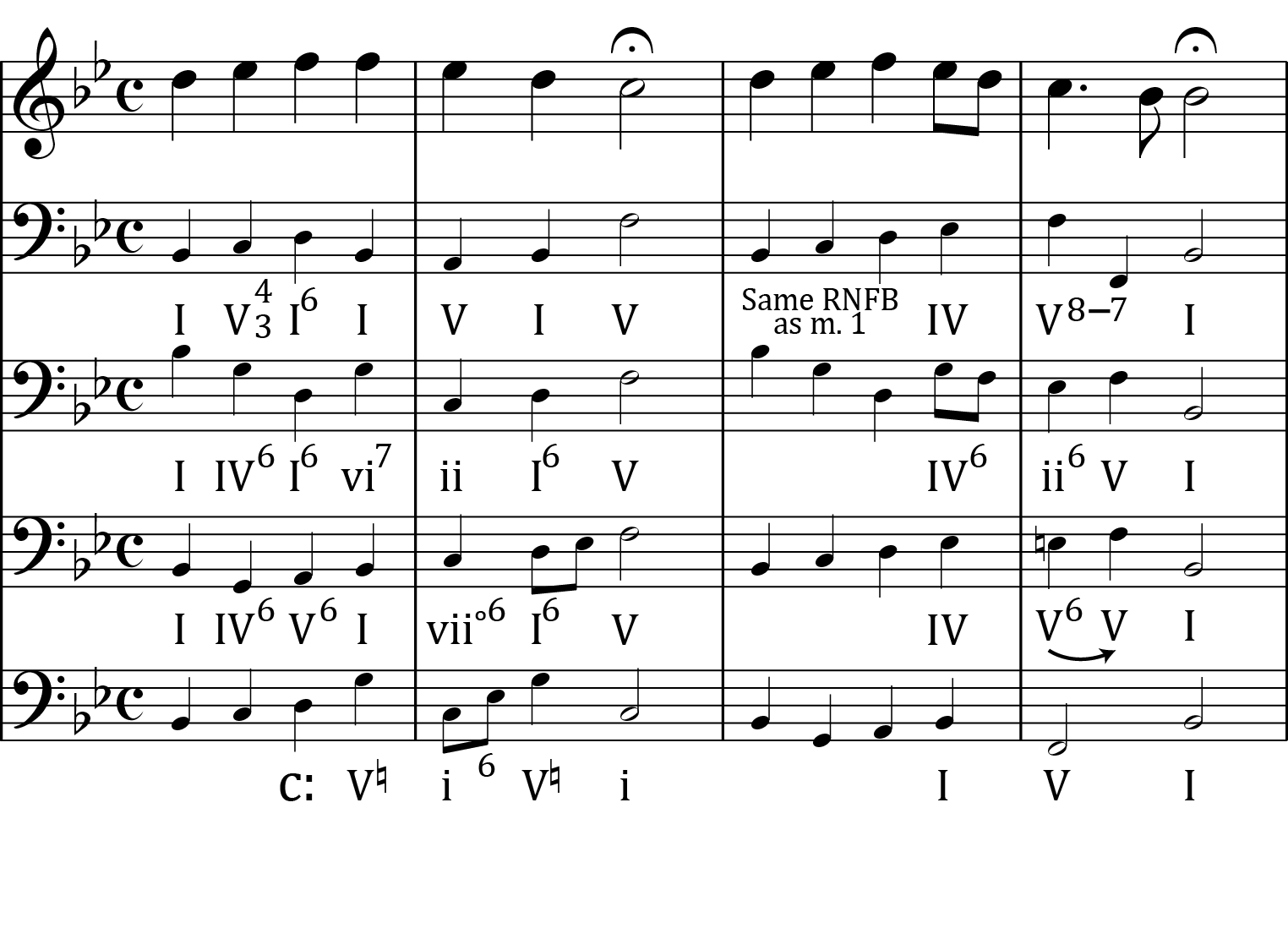

A melody can be given with or without rhythm and meter. When introducing this inverted approach, and later when dealing with longer or more ornate melodies, I provide the melody’s rhythm and meter so that students can more readily consider implied harmonic rhythm and embellishing tones. (Here is a more advanced assignment based on melodic fragments given without meter or rhythm.) Fig. 7 provides the first two phrases of a chorale set twice by Bach (#95 “Werder munter, mein Gemüthe” and #350 “Jesu, meiner Seelen Wonne”) that my students analyze in the first year of the theory sequence, after having studied harmonic expansions, phrase functions, and cadence types.

Figure 7. Two chorale phrases with possible bass and harmonizations.

While these phrases could be assigned as model compositions in the chorale style, the emphasis in an inverted analysis is to quickly generate as many possible bass lines, harmonic expansions, and cadential chords as possible, a process that sends students scurrying through Bach’s chorales for options. By studying other Bach chorale cadences, some students discover the possibility of setting the first cadence as a PAC in C minor, even before they have formally studied modulation. Fig. 7 provides some of the better possibilities my students have generated in class, though it is equally useful to identify and discuss options that are problematic or unstylistic. At the end of the exercise, students analyze Bach’s own harmonizations and compare them to the possibilities they generated. Examining Bach’s compositional choices is made more interesting by knowing the options he forwent. More importantly, the inverted approach explores the compositional process, helping students perceive the relationship between theory, analysis, and practice.

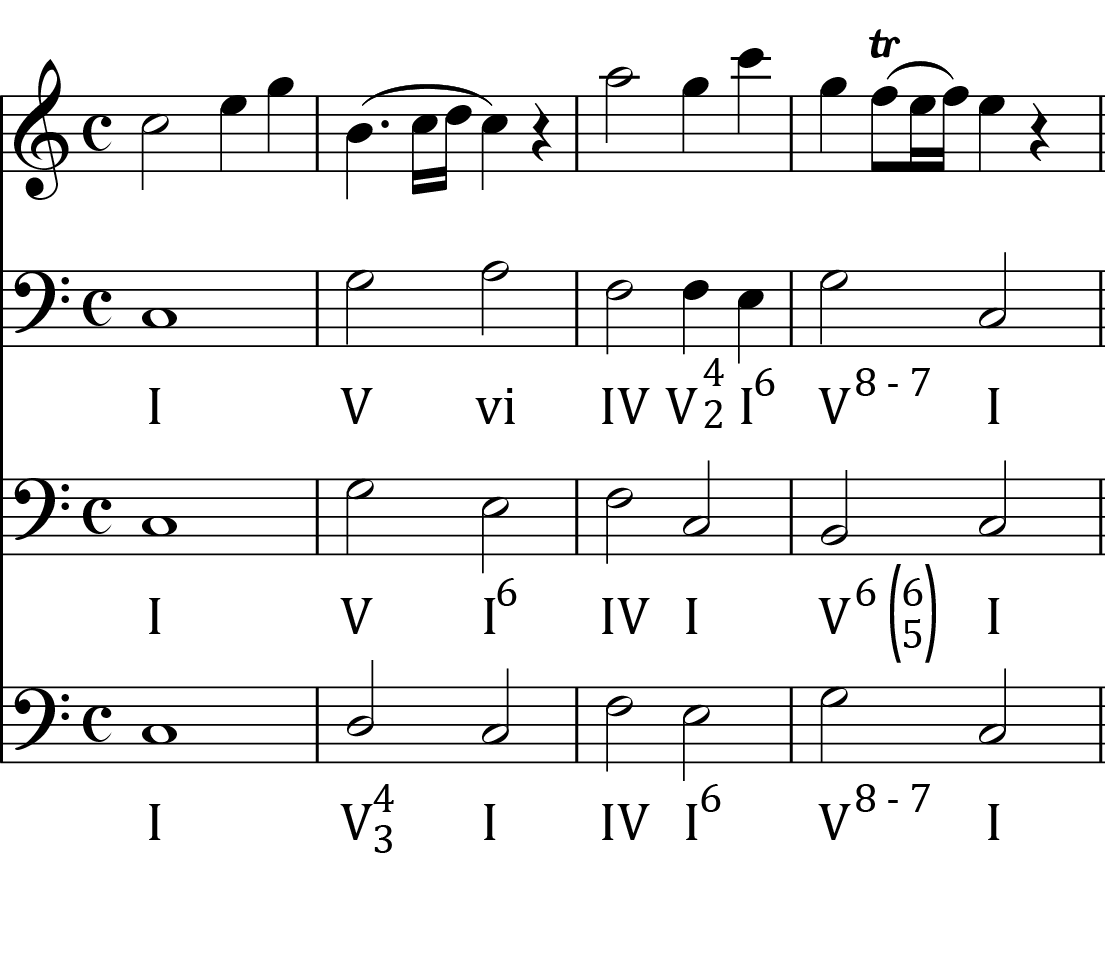

Another effective melody for inverted analysis is the first four measures of Mozart’s Piano Sonata in C Major, K. 545, shown in Fig. 8. This clear-cut melody still admits different possible harmonizations, bass lines, cadential treatment, and figuration patterns. Ten-minute “free writing” exercises like those described by Cliff Yates can generate numerous settings of this melody, which can be discussed in small groups or written on the board before finally being compared to Mozart’s setting (see Fig. 8 for some example bass lines and harmonizations). Throughout the analytical process, students discover the unique contrapuntal consequences of the bass by studying how melody notes are made consonant or dissonant. Instructors can also point out how different harmonic configurations change the way the notes of the melody are grouped and energized. Finally, this level of critical engagement, and the detailed analytical scrutiny students bring to Mozart’s sonata, help them learn music from the inside out, a valuable competency in all areas of their musical study.

Figure 8. Mozart, Piano Sonata in C Major, K. 545, mm. 1–4.

Conclusion

Inverting analysis helps instructors gauge the number and complexity of questions that students can address and connect to aural and score-based analysis. Further, instructors can engage students more effectively by choosing pieces for study that match their developmental needs.

By integrating improvisation, composition, and analysis, students learn that making music is one of the most effective means of understanding music. Every compositional problem and possibility students consider increases the critical attention they can give to the music they will hear, study, and perform. Inverting analysis invites students to explore and document the horizons of possibility within which music operates.

This work is copyright ⓒ2015 Daniel Stevens and licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution–ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.</p>